Perfumers are beginning to dip their toes, or should I say noses, into the shiny new world of tech, sustainability, gender fluidity and, of course, ‘clean’ products.

But for many years the ancient art of perfumery seemed impervious to the advancements of the modern world. Production techniques got smarter, but the basic product remained the same. This is in part, due to the intrinsic nature of scent, it is unremittingly physical.

Christian Dior once said: “A woman’s perfume tells more about her than her handwriting,” and if this logic is anything to go by then we are all frightfully unoriginal. This year’s bestselling perfume is Chanel Coco Mademoiselle followed closely by Chanel Chance, both of which have consistently topped perfume sales in the two decades since their release. But for the first time in a century, the powerhouse designer brands’ monopoly over the perfume market is beginning to loosen.

Consumers are turning their noses up (sorry) at the idea of “a signature scent”, long peddled as a prerequisite to sophistication, in favour of several products all at once. A century’s lack of innovation means that the chances of smelling like four other women on your tube are very high. This dearth of originality has led women to ditch their old perfume allegiances in search of more exotic pastures. In the last seven years boutique brands, such as Diptyque, Le Labo and Byredo, have gone from relatively unknown to cult favourites, despite their eye watering price tags.

Josephine Fairley, founder of The Perfume Society and chocolate company Green & Blacks, believes that perfume is in the position where food was twenty years ago. “People are waking up to the fact there are stories and ingredients behind scent and perfume. It’s a whole universe that we are just beginning to explore and we are seeing that people are spending more money on fragrance than clothes.

In the search for a unique scent we are also becoming more experimental in our choices. Brands have responded by producing less saccharine, often-divisive scents – leather-based perfumes, for example, are enjoying a moment.

Gucci has responded to the growing demand for exclusivity with a range of 14 “couture” oils, scented waters and perfumes called The Alchemist’s Garden. Influenced by “the art of alchemy”, the rococo bottles are meant to be layered over each other to create myriad different scent combinations. As fiddly as this may sound, the line has proved exceedingly popular with consumers increasingly looking to build “scent wardrobes”.

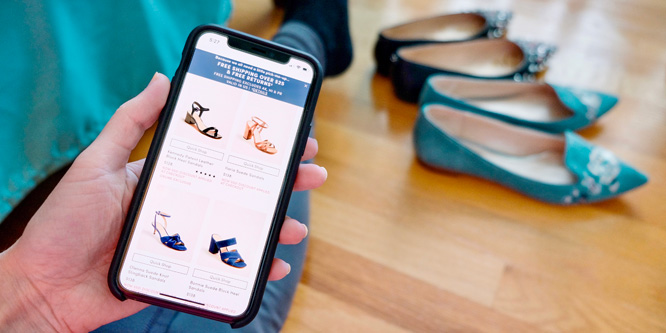

“We are not content with one perfume anymore,” explains Fairely, “like a pair of shoes, you need different pairs for different occasions, the same goes for scent. We want smaller, more affordable sizes, too – and for younger consumers, it’s about how a fragrance makes us feel as well as what it smells like.”

And many smaller brands are cashing in on our millennial obsession with “experience”. Sillages Paris targets millennials’ digital fluency with an online fragrance service. Customers take a questionnaire and a computer algorithm creates three different fragrances that are sent to the customer to test at home. Similarly, Parisian perfumers Ex-Nihilo and Shoreditch-based The Experimental Perfume Club provide a service to design and create your own perfume, both have proved so popular they are often fully booked for months.

This new generation of “woke” consumers is also rejecting preconceived notions of “masculine” and “feminine” scents and gravitating towards gender-neutral fragrances. Liberty Londonreported a 40 per cent rise in gender-neutral perfumes sales in 2018, with brands like Maison Francis Kurkdjian and Escentric Molecules leading the pack. Fairley says that floral and fruity fragrances being marketed at women is a relatively new western innovation. “Some argue it was Chanel No.5 that sparked the new (sweeter) scent of femininity, but in the Middle East, for example, it’s very normal for men to wear floral oils and women to wear spicier perfumes.”

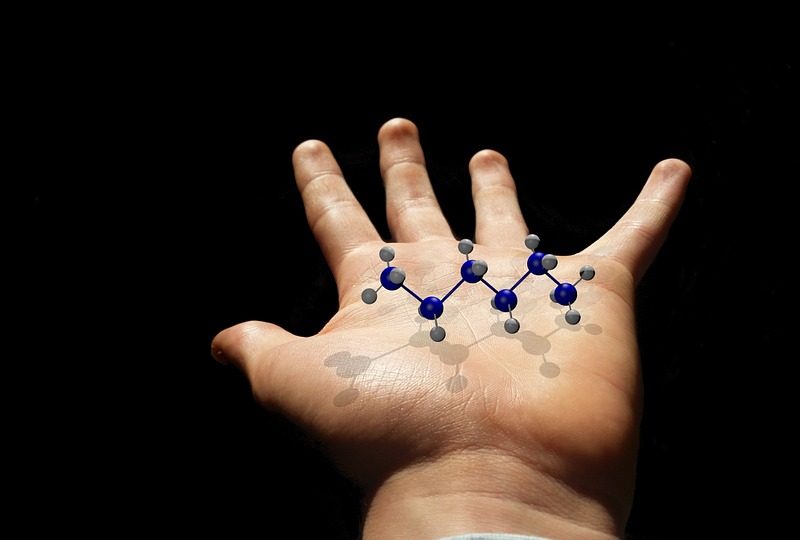

While the conversation around gender-fluidity is breaking down perfume distinctions, the ‘clean-living’ movement is also leaving its mark on the world of fragrance. “Clean perfume” is essentially fragrance without any toxic ingredients and chemicals. Last week, the actor Michelle Pfeiffer launched her own line of clean perfume called Henry Rose that, she claims, will contain zero “toxic” substances. The biggest concern for Pfeiffer and those spearheading the clean perfume movement are phthalates, chemicals that can mimic hormones and are mostly used as plasticisers. Although, some experts have called clean perfume a fad noting that in the EU phthalates are already banned. Either way, greater transparency about what goes into our perfumes can only be a good thing.

Fad or not, the world of perfume is finally moving with the times. Deaf and dumb activist Helen Keller once said that “scent is the fallen angel of our senses” but with advancements in technology, new scent combinations and consumers increasingly engaging in the production process, perhaps for the first time in a century this is about to change.