Scents and smells provide us with unique clues about the environment but, unlike animals or plants, humans massively under-use this wealth of olfactory information. This will change in 2021, and smell will be treated as data to enhance products in real time and in response to users’ engagement.

Smell-based communication has been mooted for some time, but in 2021 we will see sophisticated ways of encoding, recording and reporting olfactory signals. Processing of olfactory data will be added to search-engine/voice-search queries and integrated with multimedia information for sales, marketing, public messaging and educational purposes. Companies such as Olorama Technology, based in Valencia, and Aromyx in Mountain View, California, are already developing smell simulators, voice-activated scents and bespoke odours tailored to individual projects and customers’ needs.

The use of smell for detecting unique and specific aromas is a learnable skill and training of the nasal passages will be part of progressive education curricula. New partnerships in the public-education sector will ensure the development of training and apprentice schemes geared towards changing teachers’ perceptions and talents regarding the importance of smell in learning. Educational resources (such as scratch ’n’ sniff cards for vocabulary teaching or scented books for fuller story immersion) will be used to facilitate memory retrieval and reading comprehension in primary and secondary students. With my colleagues, we are conducting trials using olfactory books that connect specific smells and children’s learning of new words.

The brain structures common to odour and emotion processing – the amygdala, hippocampus and insula – were identified a decade ago, but the connection between mood disorders and olfaction has been underrated in medical practice. In 2021, medical practitioners will use intravenous olfactory tests to detect and prevent olfactory dysfunction. Currently used in Japan, such tests are more affordable and do not require specialised labs (unlike standardised olfactometers). They involve an intravenous injection of Alinamin, which produces a garlic-like odour sensation and is used as part of subjective olfactory tests.

Increased use of antiseptics and sanitation products, and an altered sense of smell in Covid-19 patients, will decrease natural olfactory sensitivity among the general population, raising the risk for behaviour and mood disorders. Pharmaceutical companies will capitalise on the known olfaction/emotion interactions, such as the effects of citrus-based fragrances to treat depression and anxiety.

Olfactory data will be embedded into new interfaces, which will be leveraged for monitoring and maintaining routine tasks. For example, using dynamic GPS tracking and environmental-odour detection, driver behaviour will be checked for adherence to scheduled meal breaks or length of engine use. The Cybernetic AI Self-Driving Car Institute proposed an “e-nose” for AI self-driving cars in 2018. In art, perfume-based artworks, such as those modelled by Martynka Wawrzyniak’s olfactory self-portrait, will use aromatic elements and biological oils extracted from the human body to create bespoke self-expressions.

Given that many natural scents are disappearing, there will be significant availability problems around essential oils, such as jasmine or sandalwood, that cannot be synthetically produced. New legal and regulatory frameworks might need to be established to protect the preservation of unique natural smells such as rose or lavender. The fragrance industry will adapt to the environmental degradation processes by producing perfumes based on completely synthetic smells.

However, 2021 will be a rough year for the natural perfume industry, with many artisan producers facing barriers to entry thanks to the over-regulation and homogenisation of the market.

Natalia Kucirkova is professor of reading and children’s development at the Open University, UK, and the University of Stavanger, Norway

Source: We’re about to start sending messages with our noses | WIRED UK

Multisensory communication

Not quite the sensory internet but Wok ‘n’ Stroll’s Karni Tomer creates virtual experiences so real you can taste them | WIT

Speed dating study investigates the importance of sight, sound, and scent on partner choice | Psypost

Fox scents are so potent they can force a building evacuation. Understanding them may save our wildlife | The conversation

A Sexual Wellness Revolution With The Release Of The Groundbreaking Satisfyer Connect App | Stockhouse

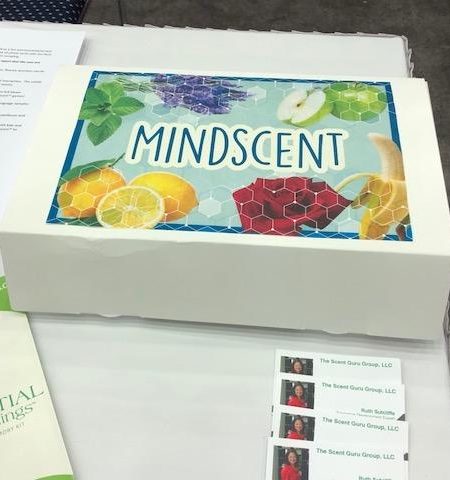

Mindscent® Is The Latest Tool That Is Enabling People With Autism To Communicate Better | Digital Journal