Scents of the season: Orange and clove pomanders evoke childhood memories of Christmas in England for this author

Out of nowhere, a random odor can send you hurtling back to a childhood memory, and you won’t know why. Smell is one of our most powerful senses, and it’s powerfully under-researched.

Our sense of smell is as important as all the other senses — seeing, hearing, taste, and touch. To some, it may even be one of the more important ones, as it relies on the subconscious. It taps into things we cannot understand.

Odors can bring pleasure and ring warning bells. They are emotional. Some researchers say that kissing may have originated from a desire to first smell a partner — before our lips ever connected.

That’s deep.

And, yet apparently, we are unable to evoke smells in the same way we visualize — in our minds’ eye — paintings, photos, people, or other things we’ve seen, done and experienced.

Just think back to the first time you met a friend or the first partner you ever kissed. You may remember exactly what they wore and what you talked about. You may even be able to hear the conversation in your head. But you would have a hard time evoking how they smelled or what other smells you picked up around you. Indeed, you may remember the smells by name — like “they smelled of apple pie” — but could you actually smell that in your mind?

Scents of the season: Orange and clove pomanders evoke childhood memories of Christmas in England for this author

Probably not. I certainly couldn’t, try as I might.

But, then, out of the blue you’ll catch that person’s scent as vivid as anything. It will be there at the tip of your nose, tingling the very hair in your nostrils. It’ll be a breeze of autumn leaves, fresh baked Christmas cookies, or an orange and clove pomander. All of a sudden you’ll be transported back to some childhood memory.

And it is usually childhood memories that smells evoke.

At least, that’s what some scientists say.

This toilet’s got an observation deck

With me — and this is where it gets a bit disgusting — I sometimes get that feeling with fresh, healthy-looking dog poo on the streets of Cologne.

Now, I’m not weird — not totally, anyway — but strange as it seems, I strongly associate the smell of fresh poo with the German city where I now live.

I think it’s because when I was a child and we visited my grandmother in Cologne, it was summer and there was always poo in town, a sight I seldom saw in London, where I grew up.

Then there was the odd experience of having to lay my own childhood cables in a toilet with an “observation deck” or “coastal shelf” as it were. They were standard back then in Germany — toilets with a Flachspülbecken. You didn’t poo into a pool of water, but instead onto a relatively dry deck. Your poo would sit there, curled in a bun, ready for inspection, until you washed it away with a thrust of water.

Somehow, it’s just stayed with me.

It’s a very visual memory, too. But I can’t for the life of me smell it until I’m met with one of those mysterious, out-of-the-blue, wafts … And I’m back in my Oma’s flat, aged about nine, laughing my head off because I’ve just left a turd in all its stinky glory for my brother to find there on the deck. (He and my Oma were not impressed.)

What’s happening?

Some research suggests that our sense of smell is linked closer with memory than other senses. I would take issue with that since (I feel) I have an uncanny memory of what I’ve seen, especially roads and routes in places I go to once and to which I return years later. I won’t remember the names of the streets, but I will recognize my way around town. So, if anything, my own senses seem to be on a par with each other.

But I digress.

When we smell, olfactory neurons in the nose send signals to a part of the brain called the olfactory bulb.

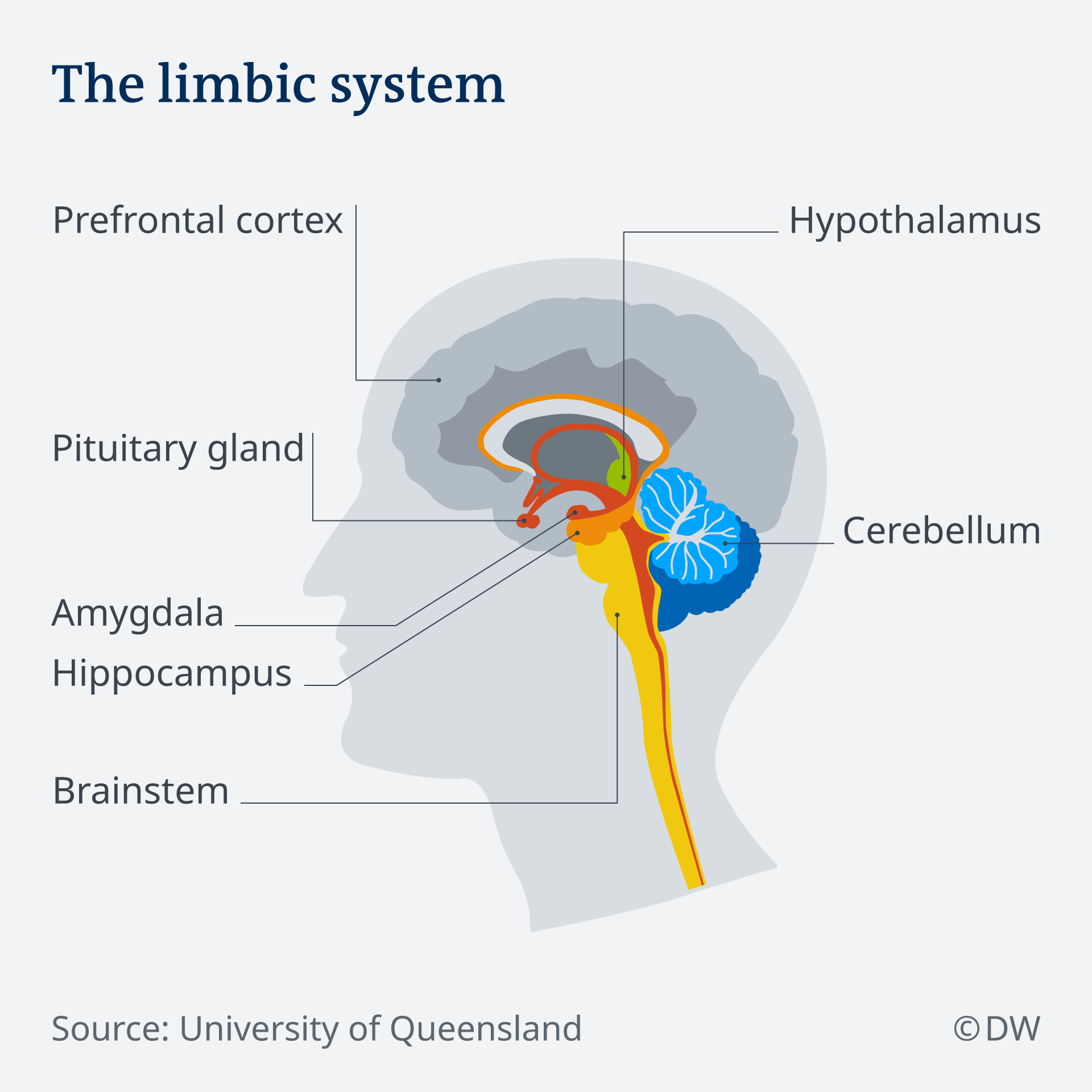

The olfactory bulb processes those smell signals and sends the information further up the chain to another part of the brain — the limbic system.

And this is interesting because scientists say the limbic system controls emotion, mood, behavior and memory.

It is home to two major structures in the brain.

First, there’s the hippocampus, where episodic memories are formed and stored long-term. The hippocampus is also relevant for our spatial awareness and ability to find our way around places.

Second, there’s the amygdala, which ties emotional content to our memories, the good and the bad.

So a sudden, unexpected waft of 4711 Eau de Cologne may send you back happily into the arms of your grandmother. It might, on the other hand, fill you with fear if it reminds you of an unhappy time you sent in hospital having your tonsils out.

We can all relate to that. But a lot of the evidence for smell memory is anecdotal.

Why is it always childhood memories?

Sorry. It’s not always childhood memories. And we don’t quite know why. Our sense of smell is probably hugely complex, but it’s also under-researched.

There have been studies into the effects of “olfactory flashbacks” in people with

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Check Judith K. Daniels at the University of Groningen and Eric Vermetten at Leiden University Medical Center for that.

There are new technologies: Judith Amores, a researcher at MIT Media Lab, wants to use olfactory science to create a mood altering sensory interface with the subconscious. The prototype looks like a test tube around your neck that spurts out smells and that’s connected to your devices a wearable. That will be an interesting one to watch, given that most of us are unconscious of how smell works. And Amores knows that.

Others have looked at “taste and odor recognition” memories.

And most recently, neurobiologists at the University of Toronto said they had uncovered an unknown brain function that may now explain how odors are recreated in memory. This could, according to the team, also help explain why one of the earliest symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease is a loss of our sense of smell.

But we still don’t know why the memories odors evoke so often stem from our childhoods.

Research by Maria Larsson and Johan Willander at Stockholm

University in 2009 suggested that memories triggered by olfactory information were stored in the first decade of life.

And I would suggest that may have to do with the fact that a child’s senses are simply extremely sensitive, and our senses get dulled as we grow older, or more accustomed to our environments. We’re no longer shocked by smells, and it no longer gets logged as special, as we’ve smelt it all before.

But, then, I’m just the kid who “forgot” to flush his poo.