The other day, I walked into the YWCA changing room to find two buck naked women screaming at each other in the showers.

The Vancouver Y, like many places, has instituted a scent-free policy. The battle was over one woman’s use of fragranced body wash, and the other woman’s towering fury sparked by the smell.

This might seem a bit of tempest in a shower stall, but the incident lingered. It wasn’t simply the spectacle of naked women yelling, it was the clear indication that a new line had been drawn.

Scent is a battleground.

We have just emerged from the year’s largest perfume-buying season, when the tang of mandarin oranges and the sweetish funk of eggnog are combined with blasts of Estée Lauder or Tom Ford. You can’t go anywhere without being suffused in fragrance, whether it’s ambient scent in a mall or a bathroom air freshener. But is this stuff benign or malign? It depends on who you believe and who you trust.

On one side, you have various studies insisting that fragrance is the new second-hand smoke, and on the other you have an industry worth billions maintaining that everyone should smell nice.

It’s a bit of an uneven fight at the moment.

A bottle of Chanel No. 5 is purchased every 30 seconds around the globe and perfume marketing campaigns, as big and shiny as Julia Roberts’ two front teeth, bedazzle the senses with nonsensical madness.

Even as researchers warn about the chemical overload of highly scented products, from garbage bags to dish soap, the market continues to expand. It isn’t simply stuff you spray on your pulse points; the very air must be adorned. Sales of perfumed candles have soared, and the global air-care market is expected to reach $12 billion by 2023.

It’s one thing to yell at a person for using perfume. It’s somewhat more complicated to yell at the atmosphere.

The market for essential oils as a panacea for all ills has also exploded. Fragrances like peppermint, frankincense and rosemary are touted as aiding in sleep, improving memory and even curing cancer. Although some studies have shown that essential oils work better than antibiotics for healing infection, large-scale research has yet to be undertaken. As the wellness industry seeps into self-care, people are cocooning themselves in veils of scent.

But what is really behind the meteoric rise of essential oils, scented candles and perfume diffusers?

I think the trend is fuelled by something more complex than marketing. It harkens back to the sense of smell itself. How it works in the human mind and body, and why we retreat to the world of comforting things, even when we might get yelled at for doing so.

Here I must out my bias. I am on the pro-smell side. Maybe because it connects so immediately and intimately with time, place and perception. Smell is life. If you are about to die, your sense of smell is the first thing to go.

Dollars and scents

The first time I went to Paris, my major purchase was a bottle of perfume — Mandarine Tout Simplement from L’Artisan Parfumeur. The bright orange bottle with its matching diffuser seemed to me the dizzying heights of sophistication, and the scent itself was the perfect embodiment of mandarin oranges. Short of peeling one and rubbing it all over yourself, which is sticky and attracts wasps, it was basically an orange in a bottle. It was love at first sniff, and the smell itself became emblematic of Paris, of excitement and sweetness and of a kind of joie de vivre. I used every drop and the empty bottle still sits on my nightstand.

On a recent trip to Paris, I visited Jovoy, the Mecca of French perfume, situated beside the Jardin des Tuileries and a few blocks from the Louvre. Jovoy is a hushed sacred space, quiet as a library, full of dark wood, glittering decanters and severe looking salespeople, who simply stare at you in dead silence when you try to make small talk.

It is a serious store full of serious scents. If brands like Elizabeth Arden or Calvin Klein are akin to mid-range restaurant food (The White Spot of perfume), the fragrances at Jovoy are haute cuisine — rare, expensive and created for refined palates.

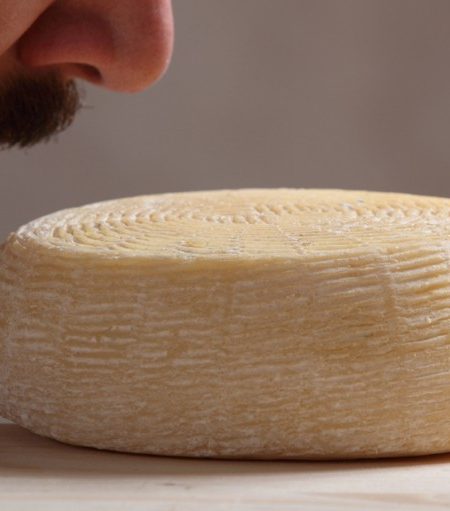

This shit is the real deal, and sometimes it even contains shit, tiny trace elements of civet paste, or whale barf, or antelope spunk — things that you might turn up your nose at. But in small amounts they add heft, depth and longevity to a perfume. French folk have a greater tolerance for animalic (musk) and indolic (poop) scents than their North American counterparts. These terms and others, like sillage and throw, are used by perfumers to denote how long a scent lasts and how far away you can smell it. Like national cuisines, perfume can be identified by its country of origin. Japanese fragrances tend towards cleaner water-based scents, whereas oud (derived from the resin of the agar tree) is the base ingredient in many Arabic perfumes. Each tradition comes trailing ribbons of history and culture, some thousands of years in the making.

But the modern fragrance industry has long relied on synthetic scents because they’re cheap and easy to mass produce. Some of these chemicals make civet emissions look positively benign.

Australian author Kate Grenville meticulously documented the darker practices of the perfume world in her book The Case Against Fragrance, outlining the number of known carcinogens and highly toxic chemicals used by the industry.

Although fragrance is ubiquitous, it is largely unregulated. Perfume can be composed of hundreds of different chemicals. People who react badly to the stuff aren’t making it up, or trying to be hectoring and unfun, they’re genuinely ill. In Grenville’s case, the scents brought debilitating migraines. Others suffer different symptoms. As chemical sensitivities become an ever-larger issue, and massive corporations are forced to settle multimillion-dollar lawsuits over toxic ingredients, the lowly sense of smell seems caught in the middle.

The human sense of smell evolved as a means of survival. It is the oldest of our senses, originating from a time when people needed to sniff out the difference between life and death. Bad smells could kill you, and good smells could save you. As chemical stand-ins have largely replaced real scents, it is increasingly difficult to discern the difference between these two things.

Nosing around for a mate

The sense of smell and all of its permeations — memory, emotion and history — were exquisitely ravished by author Diane Ackerman in her 1990 book A Natural History of the Senses. Right on the nose is where Ackerman begins, with an exhaustive examination of what the sense of smell means to humans. Her prose, luscious and purple in places, is dripping with sensorial language in an effort to describe scent. But even Ackerman admits that writing about perfume is tricky. An orange smells like an orange. A violet like a violet.

It is interesting to revisit Ackerman’s work in this more puritanical age, when people are actively policing what other people smell like. I have some sympathy for both sides. Certainly those with chemical sensitivities shouldn’t be subjected to smells that make their heads explode, but the idea of a world without fragrance seems a diminished one.

Smelly stuff interests me. Not only people, but places, animals, plants, and even periods of time. Most people have some secret scent fetish, whether it’s horse shit, creosote, diesel fuel, Sharpie markers, warm dirt, hay or the smell of a grandparents’ house, long vanished from the Earth but still, somehow, remaining inside your brain. Good perfumers treat the creation of a scent like a symphony, composed of different acts and movements. Top notes melt into midrange and then bottom out into bases of amber, vanilla or cedar.

Much of what we perceive as taste is in fact smell. People with bad head colds often can’t tell the difference between an onion or apple.

The old Proustian notion of scent opening up pockets of memory is well worn. But perfume is determined by and reactive to larger cultural shifts. No one who came of age in the go-go ’80s can ever rid themselves of the memory of Dior’s Poison, Calvin Klein’s Obsession or Giorgio Beverly Hills. These were huge scents that could fill or clear a room. The ’90s was a time of pared back androgynous scents like CK One. Now millennials are getting in on the action with highly individuated takes like Glossier’s Glossier You, or Escentric Molecules’ Molecule O1. These are perfumes that you can’t smell on yourself, but they have the strangest effect on other people. Spray some on and expect to have folks come bounding up to tell you that you smell “amaaaaaaaaaazing.”

If you’ve ever wondered why certain smells make you happy, anxious or melancholy, or why hippies love patchouli, there are a number of books, websites and blogs devoted to the science of scent. One of the bibles comes from husband and wife team Luca Turin and Tania Sanchez, who outline not only the history of fragrance, but where it is going next and the science behind it, on a molecular level.

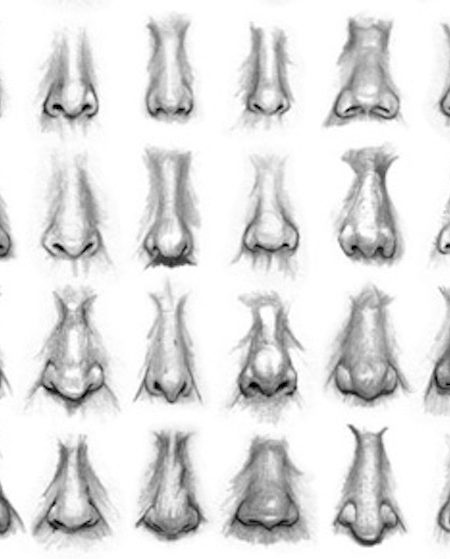

Humans have a mini-computer lodged at the top of their nostrils, an organthat translates molecules into memory, emotion, culture and, of course, attraction. Most people have, at one time in their lives, sprayed on some perfume in honour of a special occasion. And if you don’t like the way someone smells it can be very hard to like that person (and vice versa). There’s no getting around it; scent is often about sex. Kissing on the mouth supposedly originated as a way for people to sniff out prospective mates.

A whiff of life

But even as fragrance is used in almost every part of daily life, from the most mundane stuff like dishes, laundry or washing your bum, there is something that remains ineffable and mysterious. Smell is a direct link to the physical world, and smelling something, for good or for bad, means taking it inside yourself, via your nostrils, and up into your brain, wherein the real fireworks begin. It is the very essence of humanness.

Back to the naked ladies fighting in the shower for a moment. What is pleasurable to some is anathema to others, and in an age where divisions flare into conflict, it’s probably time to rethink how we share space with other people. Perhaps what we’re witnessing is also social change in action. Those who remember a time when every car and bus trip included a fog bank of secondhand smoke hanging just over your head, and the acrid stink that clung to clothes and hair afterwards, should recognize there are those who feel the same way about fragrance. And, just as we decided that smoking wasn’t something that everyone should be subjected to, mostly because it killed people, toxic fragrances may also have to go.

I know. You’re thinking about the bottle of Chanel No. 5 you gave your mother-in-law for Christmas, the Axe body spray for your nephew and the bottle of essential oil for the funky hippie down the road. But it may be time to rethink the stuff. Capitalism, ever helpful as long as it involves people spending more money, has led businesses to provide an alternative to chemical scents, natural fragrances derived from ingredients that don’t come from a lab.

But if you really want to get the benefit of the world of smell, all you have to do is step outside, find a rosemary bush, a Katsura tree or a bunch of briny kelp bulbs, and breathe it all in.

One of my favourite smells is actually a non-smell. A whiff of earliest spring in February, when some hint of incipient growth, yet to push through the earth, is more felt than smelt, tickling the sensitive instrument lodged at the top of your nose, with the promise of renewal and rebirth.

Read more: Analysis

Source: War Is Smell | The Tyee

The Connection Between Saliva And Flavour Perception? | Slurp

Scent adds more dimension to exhibits and stories & enhance perception and interaction | Denver Art Museum

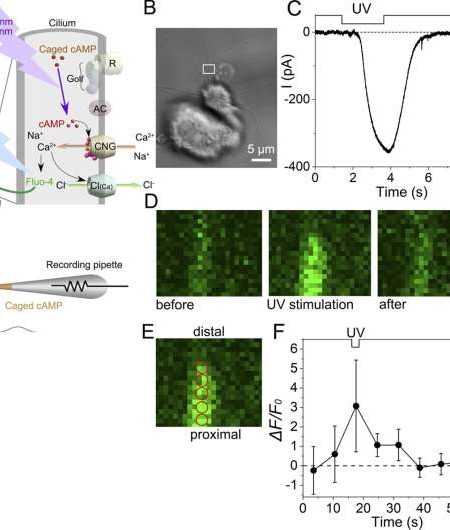

How do we smell? First 3D structure of human odour receptor offers clues | Nature

Breakthrough on ‘sense of smell’; scientists create 3D picture of odour molecule | Hindustan Times

Tasting memories: the Spanish ice-creams serving a scoop of nostalgia | The Guardian

Art made from mushroom foam, walnut ink and more featured in Sustainable Studios exhibit | lancasteronline.com