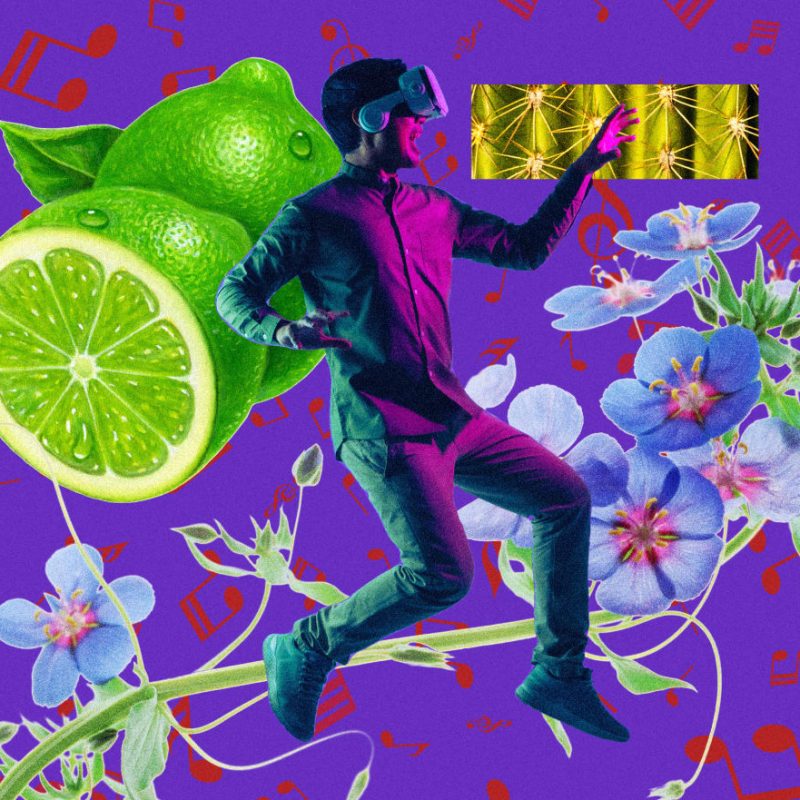

PASADENA, Calif. — I’m standing in a black void and hear a woman speak to me in a mix of frustration and pride. “The star of this dish is veal sweetbreads/i find we have much in common,” she explains in poetry, and as she speaks, illustrative brush strokes scribble and stack until a gourmet sweetbread dish and its individual ingredients float all around me. “It’s a lucky exception from the rule that offals are distasteful/an aspiration for all minorities.”

The narrator is chef, curator, and poet Jenny Dorsey, co-founder of the educational culinary nonprofit Studio ATAO, and she is describing the fourth dish of a six-course dinner while I watch the food manifest in an Oculus Rift virtual reality headset. The meal, which is also accompanied by three handcrafted cocktails mixed by her husband, Matt Dorsey, is a sensory metaphor for Dorsey’s experiences as an Asian in America — the title of her pop-up exhibition at the USC Pacific Asia Museum.

Each stage of the meal offers a different cultural critique, “from cultural hierarchies in the food system and the lack of the individualism granted to minorities to the internalization of the ‘white savior’ complex.” One plate was geometric and minimalist, with a perfectly rounded globe of fish sauce ice cream and a cake made of mole sugar and chapulines — a type of grasshopper — delicately balanced over bone marrow gel, surrounded by pearls of persimmon moose and small towers of pear. This dish represented the white savior complex — each component described as a white male chef’s signature. “Andy’s fish sauce caramel ice cream” and “Rick’s chapulines cake with mole sugar” showed how Westerners use ingredients associated with Asian or Mexican cuisine and claim them as their own by attaching authorship to their creations.

Asian in America’s real-life dining experience debuted back in 2018 at New York City’s Museum of Food and Drink, and the pop-up exhibitionat the USC Pacific Asia Museum cleverly uses VR, resin food replicas, and photography to recreate the experience. Though I couldn’t taste the haute cuisine, I could see how the virtual mise en place transformed into the beautiful molds set out before me, preserved under glass like the ancient artifacts on display in the museum’s other galleries.

The food is Asian fusion, combining traditional East Asian ingredients with French techniques or molecular gastronomy, but as Dorsey’s poetry points out, many of the cooking methods are not exclusive to Western culture. “I marinate the quail eggs a few days in advance/ the same process as tea eggs, its marbling reminding me of after-school snacks and hiking with my family,” Dorsey says, reminding me that a Michelin star restaurant may drive up the price of a dish to triple digits because it has been marinated for 72 hours, while the cheap takeout in Chinatown has been lovingly prepared for the same period of time.

While Dorsey pulls from personal experiences for her six-course meal, many audiences are able to connect with her stories. The second course searched for a balance between flavors of black sesame and rye, “like my favorite Jewish deli where I drink matzo ball soup when I’m sick.” I thought about my own Jewish heritage and the snacks my grandmother loved to eat, like gefilte fish and chopped liver.

Adelaide Zou, a volunteer, felt connected to the exhibition because it touched on her own experiences as an Asian American and how she is represented in contemporary culture. For Zou, Dorsey’s project shows how alive and influential Asian culture is in the world at present. “It’s really exciting to see it here in a museum, where [the displays are] usually cultures people see as dead. This is very much a living, breathing, organism.”

Zou also loved how the cuisine didn’t obscure ingredients that can be off-putting to Americans. One of the cocktails contained monosodium glutamate, or MSG, a staple in Chinese cooking that has been dubiously linked to ill health affects, causing restaurants to hang flashing “NO MSG” signs in their windows to avoid losing white customers. “I love that MSG is proudly and definitely stated,” Zou said. “Now that it’s elevated, what do you think about it?”

Though I longed to taste the food firsthand, I felt satisfied with the documentation, and the VR experience and close-up views of the replicas and photographs gave me a better idea of how to envision the meal than the average episode of Top Chef. It was refreshing to see that Asian in America didn’t use technology frivolously, but instead to emulate a labor-intensive experience that realistically can’t be repeated in a gallery setting. For those who weren’t able to check out the exhibition’s brief stint, Studio ATAO has made their 360-degree videos available online, which can be viewed in a personal VR headset or on a desktop computer.

Asian in America ran at the USC Pacific Asia Museum (46 N Los Robles Ave, Pasadena) August 7–11. You can now visit the project online.

Source: A Virtual Reality Meal Is a Powerful Comment on Being Asian in America