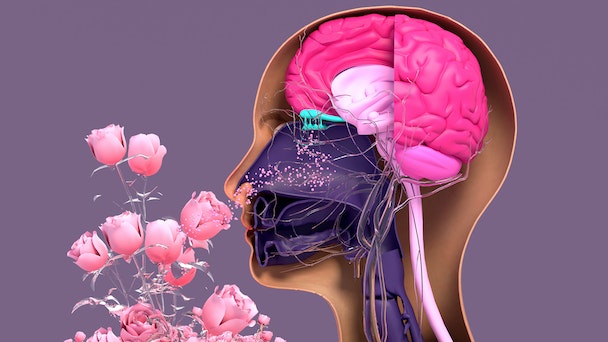

The olfactory system connects directly with the limbic system, one of the oldest structures in the human brain. / Adobe Stock

Picture yourself strapping on a virtual reality (VR) headset and finding yourself in a beautiful, virtual park, with a dazzling variety of flowers lining the walkway in front of you.

You reach down and pick a lavender blossom, hold it to your nose and inhale deeply. The scent of lavender enters into your nostrils, and from there into the limbic system of your brain – a deep, ancient structure shared by all mammals which house the amygdala and the hippocampus, the neural regions that are (broadly speaking) responsible for emotion and memory, respectively.

The smell of the small purple flower causes you to think of your grandparents’ country home, which you used to visit as a child and which had a yard richly adorned with lavender.

Suddenly, the virtual park starts to feel much more real.

Now, add to the picture of our virtual park an avatar grilling Johnsonville sausages, the smell of the meat and the smoke adding to the realism of the scene. This could very well be a thought experiment that makes marketers hungry.

To many, the notion of virtual objects being endowed with real scents will sound like pure science fiction. But in fact, it’s a rapidly developing field – one that could eventually revolutionize the experience of VR.

OVR Technology: adding scents to virtual worlds

As it stands, VR is primarily an auditory-visual experience. There’s an element of touch, too; Meta’s Quest 2 headset, for example, comes with controllers that vibrate when, for example, you’re being punched in a boxing game or when you’re moving over rough ground in a driving game. That’s the sensoral extent of the majority of VR experiences; more immersive than a PlayStation game, perhaps, but much less convincing than the real world.

But what if we could smell virtual environments?

OVR Technology, a tech start-up based in Vermont, is devoted to solving this problem. The company has built the Ion, which it describes as “wearable scent technology.” It looks a bit like a bulky set of wraparound Bluetooth headphones attached to a claw-shaped device that sits directly under the user’s nose, and which emits scents complementing one’s experience in VR. The Ion incorporates eight “primary aromas” – soft, fresh, earthy, green, citrus, floral, sweet and woody – which can be experienced individually or in a near-infinite variety of combinations.

The Ion is designed to produce an olfactory experience that parallels the visual experience within VR. “Based on what you’re doing in the digital experience, [the wearable scent technology is] triggering exactly the right scent at exactly the right time,” says Aaron Wisniewski, OVR’s founder and chief exec. “In virtual reality, the scents are often triggered spatially, by picking an object up or getting close to an object or an area that will trigger the smell. And that’s a really powerful way to create association – our brains love that context.”

One of the ways in which the olfactory sense differs from our other four senses is that it’s connected directly to the cerebral cortex, the part of the brain which facilitates very high-level cognitive processes like learning, language processing, and decision-making, “Smell goes straight to your cortex as a perception, which is really fast and which suggests it’s super powerful,” says neuroscientist Joshua Sariñana. “When you’re navigating a first-person game with a VR headset on, and there’s a smell, you will associate that smell to that place very rapidly.” In other words: our brains use our sense of smell in large part to create a mental map of the world – a neurological feature which has huge implications for the rapidly evolving and expanding realm of VR.

While the user is immersed in VR, Wisniewski explains that the wearable is “triggering scents all the time, almost the way a printer ink cartridge is printing different colors and combinations of colors” – one more layer of sensory input adding to an increasingly rich tapestry of experience in virtual worlds.

Avoiding the uncanny valley

There’s a balancing act at play here. While OVR endeavors to make smells feel realistic enough to be able to pull a subtle psychological sleight-of-hand – convincing the brain that they are in fact real – they can’t be made too convincing. Otherwise, the user will start wading into what’s known as the “uncanny valley.” You can think of this as a narrow zone separating the obviously artificial from the obviously organic, a thin sliver of space wherein simulations of reality transition from being fun and enjoyable to being disturbing – a little too lifelike.

An artificially intelligent humanoid robot, for example, could be said to be in the uncanny valley if it were able to almost but not quite perfectly simulate human facial expressions and behavior; it’d be startlingly human-like, but there’d be something that most real humans would perceive as being a little off.

How does the uncanny valley apply to olfactory experiences? As Wisniewski explains, trying to replicate smells with pitch-perfect precision is unlikely to translate well from person to person. “By trying to replicate physical smells too exactly we end up in the uncanny valley because everyone’s perception of smell is slightly different,” he says.

“Even if I were to be able to replicate [a smell] exactly right for you, nobody else would agree that it’s correct – literally nobody else. So we’ve found that creating this palette of familiar yet not-specific smells pushes your brain in a certain direction, and then it fills in the rest.”

The risk of veering into the uncanny valley is omnipresent in virtual experiences. Most virtual avatars, for example, don’t look anything like flesh-and-blood humans, but if they did, many of us might find them deeply unsettling. This is one of the reasons why some experts recommend (somewhat counterintuitively) aiming away from the lifelike, towards the realm of the strange, the experimental and the fantastical.

“There are actually sometimes more risks in shooting for realism than not,” says Hannah Seckendorf, experience design strategist at Unit9, a production company focused in part on helping brands to develop experiences in VR.

“This plays out all the time in VR, where there’s a certain amount of abstraction that we’re comfortable with interacting with … and then, eventually, it reaches a point of similarity to humanness but just missing the mark enough that it actually becomes a really eerie experience. This is where the whole avatar thing gets very complicated because you risk a really distractingly creepy experience when you try and take that amount of realism with you.”

Another problem with adding realistic smells to VR experiences is that not all smells are pleasant. Our sense of smell, along with that of taste, evolved in large part to be a poison detector – an alarm system warning us not to ingest or go near something. The smell of soured milk is your olfactory sense telling the rest of your brain: “if you drink that, you’re absolutely going to regret it.” Do we really want to add unpleasant smells in VR? Do you really want to be able to smell your virtual gym, or a dark, spooky basement infested with bemushroomed monsters while you’re playing The Last of Us?

“Maybe you don’t really want to smell zombies,” says Yates Buckley, founder and technical partner at Unit9. “So there’s a bit of a problem: the more you get access to sensory information, the more you have to decide: ‘where do we stop with this?’”

Source: What does virtual reality smell like? Marketers (and the world) may soon find out