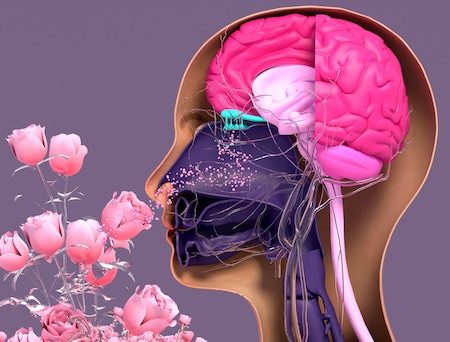

The pandemic has changed how people want themselves, their clothes and their homes to smell

A vegetarian steak is tested at the headquarters of Swiss group Firmenich, one of the world’s leading flavour manufacturers © Fabrice

Is artificial intelligence already deciding how you smell?

Before the pandemic, it was popular in America to smell sweet: a growing trend for fruit — even caramel — scents in consumer products such as shampoo or detergent had become notable. Quite what was driving this unpleasantness is not clear.

But there are signs of a shift. The Covid-19 pandemic has changed how people want themselves, their clothes and their homes to smell — and not just in America. Now people want to believe everything they touch is squeaky clean — even antiseptically so. The astringent ubiquity of rubbing alcohol has lodged itself in the public smell consciousness, sitting alongside citruses, menthols and such as a signifier of hygiene.

What people like to smell changes all the time — more gradually than seismically but with huge business consequences. Rarely do we stop to think about how much of our environment — and the products we consume in it — is scented. But almost everything is.

On the outskirts of Geneva, between the suburbs of Vernier and Satigny, is proof of how lucrative scent (and flavour) can be. This is the “Silicon Valley of smell”, says Gilbert Ghostine, the chief executive of Firmenich, one of two companies based here that dominate the way the world smells. The other is Givaudan. (IFF, a third giant of the sector, is based in New York).

Both Givaudan and Firmenich have a 10-year, compound annual growth rate in revenues of about 5 per cent. The pandemic barely dented this.

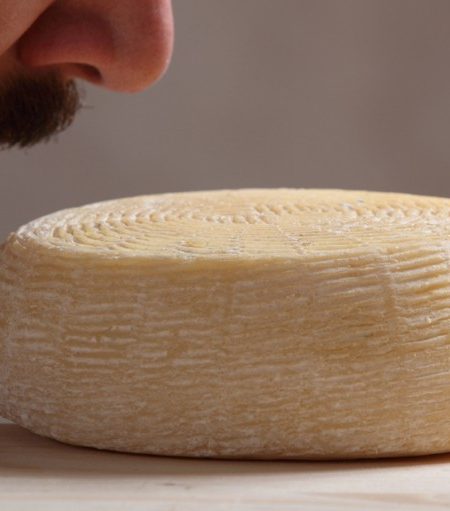

The two are fiercely competitive. Smell espionage is real and a code of silence surrounds the companies’ clientele. Both Givaudan and Firmenich like to boast about their technological prowess and the clever things they do. (This extends to food, where the world’s vegans have a lot to thank them for. So do the world’s dieters — Firmenich likes to boast it removed 1.2tn calories from food products in 2020 thanks to its sweeteners and flavour enhancers).

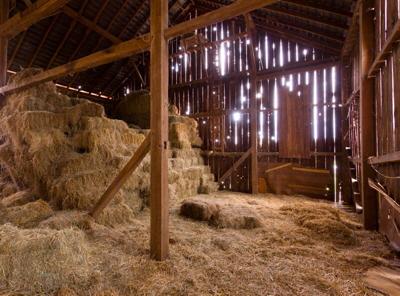

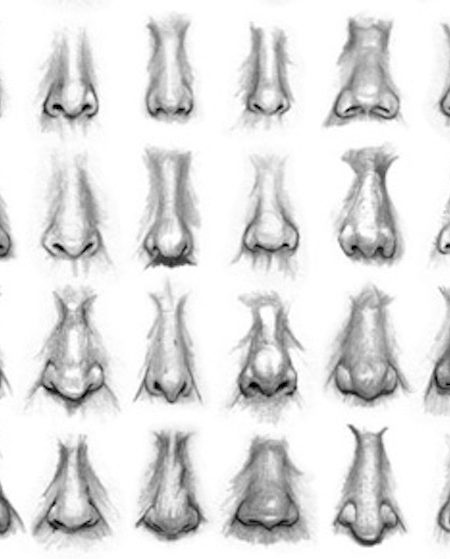

The efforts they go to are exacting, almost Willy Wonka-like. In their laboratories outside Geneva are whole rooms filled with dozens of washing machines, in which different detergents and scents are trialled on regulation sets of undergarments, towels and T-shirts. Others are full of drying racks to see what new scents smell like as laundry dries.

But the real edge these companies have is in knowing what their customers want. When it comes to staying ahead of slow, hidden shifts in the smell-desires of global consumers, data are invaluable.

Last month, Firmenich launched its “scentmate” portal. Customers no longer need to liaise with an expensive perfumer to work out what they want their new candle, washing powder or moisturiser to smell like. They can simply upload their preferences to the portal — Something fresh? Something heady? — and an algorithm will churn out recommendations.

This is particularly powerful as the world globalises, an key driver of sector growth. The extent to which products need to be adapted to local cultural tastes and expectations is more and more important. Fragrances that evoke air-dried clothing and urban-escapism might be very different in England than, say, Thailand.

So the portal allows customers to specify other factors such as geography and price, too, in order to recommend scents to suit needs. It is backed up by a constant stream of consumer data, gathered from testing panels across the world. Givaudan has also identified data and digitisation as vital to transforming how it pitches and sells its scents.

This big data of smell might show, for example, that clove is becoming a more popular aroma among east London hipsters in high-end cosmetics — and that historically that market has led scent preferences in Berlin among a similar demographic, with perhaps a two-year lag time before take-up in broader consumer markets.

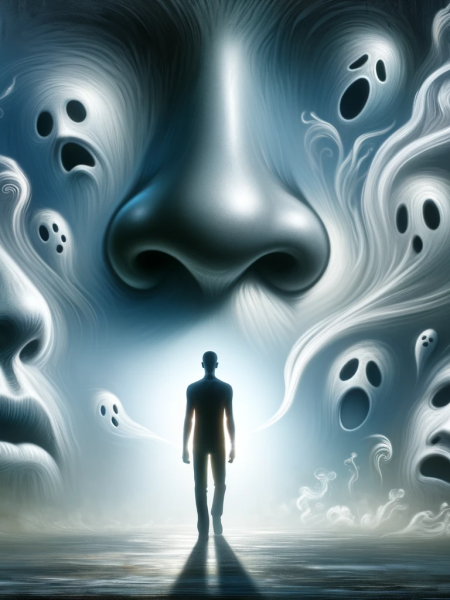

All of which is not to say that the perfumers’ art is over. In fine fragrance, the noses of scent’s Silicon Valley are being asked to source ever more unusual and aggressive smells. Uniqueness and originality are the signifiers of elite status. So much so that even “animalistic” and “faecal”’ smells are making their way — albeit in small amounts — into expensive new fragrances, one perfumer told me. Scentmate could not predict that.

This could also tell us something about the way AI and big data will impact our lives more broadly. The big social divide in the future may be between those who can afford to be original, and those whose tastes are shaped by algorithms.

Source: Switzerland’s ‘Silicon Valley of smell’ prospers in age of big data | Financial Times

Multisensory AI/VR

Could the metaverse help predict and produce movie blockbusters? | World Economic Forum

Why Clinique’s Next Move In The Metaverse Is A Winning Formula For Web3 Retail | Forbes

Study: New VR sensory room reduces anxiety in people with intellectual disability | MobiHealthNews

‘Thinking about beauty in a new way’: How brands are pursuing multi-sensory strategies in the digital world | Cosmetic Design

Multisensory smell

The Connection Between Saliva And Flavour Perception? | Slurp

Scent adds more dimension to exhibits and stories & enhance perception and interaction | Denver Art Museum

How do we smell? First 3D structure of human odour receptor offers clues | Nature

Breakthrough on ‘sense of smell’; scientists create 3D picture of odour molecule | Hindustan Times