- Human hippocampal connectivity is more robust in olfaction than other sensory systems.

- The primary olfactory cortex in humans evolved without re-routing functional connectivity between the brain’s “memory hub” (i.e., hippocampus) and smell system, new research suggests.

- Olfactory-hippocampal connectivity oscillates with the respiratory phases of nasal breathing.

- Olfactory-hippocampal connectivity is maximal in theta (4-8 Hz) brain wave range.

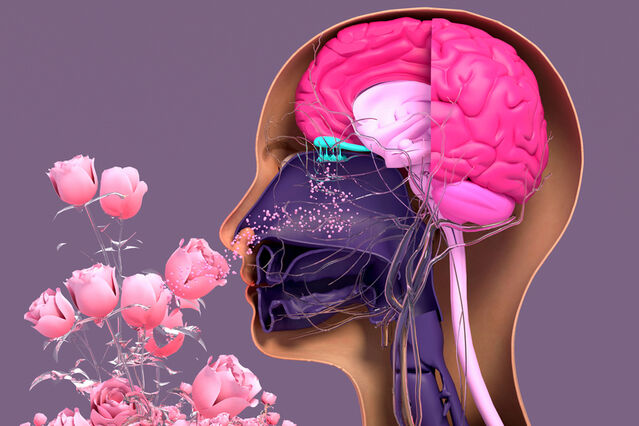

Scent travels on an evolutionarily-preserved superhighway of functional connectivity that directly links the hippocampus (memory hub) with the olfactory system, according to a new study (Zhou et al., 2021) from Northwestern University. This paper was published on February 25 in the peer-reviewed journal Progress in Neurobiology.

Whereas other sensory systems are thought to have been re-routed during human evolution, this study suggests that olfactory-hippocampal functional connectivity was preserved and not re-routed. “We show that [the] human primary olfactory cortex—including the anterior olfactory nucleus, olfactory tubercle, and piriform cortex—has stronger functional connectivity with hippocampal networks at rest, compared to other sensory systems,” the authors write in the paper’s abstract.

For this study, senior author Christina Zelano and colleagues in the Northwestern Human Neuroscience Lab used functional neuroimaging (fMRI) combined with intracranial electrophysiology (iEEG) to directly compare the functional connectivity of hippocampal networks across a wide range of human sensory systems (e.g., auditory, touch, visual, and smell).

Zelano and her lab members speculate that olfaction was not re-routed during mammalian evolution; therefore, we have especially robust functional connectivity between our olfactory system and memory hub. “It’s like a superhighway from smell to the hippocampus,” the authors note.

“During evolution, humans experienced a profound expansion of the neocortex that re-organized access to memory networks,” Zelano said in a news release. “Vision, hearing, and touch all re-routed in the brain as the neocortex expanded, connecting with the hippocampus through an intermediary—association cortex—rather than directly. Our data suggests olfaction did not undergo this re-routing and instead retained direct access to the hippocampus.”

Almost a century ago, Marcel Proust explored how smells and taste can trigger vivid, involuntary memories in his seven-volume novel, À la recherche du temps perdu (translated as In Search of Lost Time or Remembrance of Things Past). In the novel’s first volume, Swann’s Way, the narrator famously dips a piece of madeleine cake into a cup of tea; the smells and flavors held in this madeleine soaked in tea unlock his memory banks and trigger instant flashbacks to his childhood.

Below is an “episode of the madeleine” excerpt from Swann’s Way by Marcel Proust (c. 1922):

“[One] day in winter, as I came home, my mother, seeing that I was cold, offered me some tea, a thing I did not ordinarily take. I declined at first, and then, for no particular reason, changed my mind. She sent out for one of those short, plump little cakes called ‘petites madeleines,’ which look as though they had been molded in the fluted scallop of a pilgrim’s shell. And soon, mechanically, weary after a dull day with the prospect of a depressing morrow, I raised to my lips a spoonful of the tea in which I had soaked a morsel of the cake. No sooner had the warm liquid, and the crumbs with it, touched my palate, a shudder ran through my whole body, and I stopped, intent upon the extraordinary changes that were taking place. An exquisite pleasure had invaded my senses, but individual, detached, with no suggestion of its origin.”

The narrator, Swann, goes on to describe how the smell of a petite madeleine cake dipped in tea suddenly brings back a wave of memories from his childhood in Combray, France. He asks, “Whence could it have come to me, this all-powerful joy?” and says “I was conscious that it was connected with the taste of tea and cake, but that it infinitely transcended those savors, could not, indeed, be of the same nature as theirs. Whence did it come?”

The recent discovery that human hippocampal-olfactory connectivity is stronger than the functional connectivity between other sensory systems helps to answer Swann’s age-old question of how smells from our past trigger reminiscence and sheds light on the neurobiological origins of so-called “Proustian” memories.

When asked, “Why do smells evoke such vivid memories?” in a Q&A from Northwestern’s news release, Zelano responded:

“This has been an enduring mystery of human experience. Nearly everyone has been transported by a whiff of an odor to another time and place, an experience that sights or sounds rarely evoke. Yet, we haven’t known why. The study found the olfactory parts of the brain connect more strongly to the memory parts than other senses. This is a major piece of the puzzle, a striking finding in humans. We believe our results will help future research solve this mystery.”

COVID-19 and the Olfactory-Hippocampal (Memory Hub) Link

Previous research suggests that experiencing a loss of smell is associated with an increased risk of depression and lower quality of life. Because many people who test positive for COVID-19 also report losing their sense of smell and taste, olfactory research is of growing importance to the psychological well-being of these patients.

“While our study doesn’t address COVID smell loss directly, it does speak to an important aspect of why olfaction is important to our lives: smells are a profound part of memory, and odors connect us to especially important memories in our lives, often connected to loved ones,” Zelano said. “The smell of fresh chopped parsley may evoke a grandmother’s cooking, or a whiff of a cigar may evoke a grandfather’s presence. Odors connect us to important memories that transport us back to the presence of those people.”

“There is an urgent need to better understand the olfactory system in order to better understand the reason for COVID-related smell loss, diagnose the severity of the loss, and to develop treatments,” first author Guangyu Zhou added. “Our study is an example of the basic research science that our understanding of smell, smell loss, and future treatments is built on.”

“Most people who lose their smell to COVID regain it, but the time frame varies widely, and some have had what appears to be permanent loss,” Zelano concludes. “Research like ours moves understanding of the olfactory parts of the brain forward, with the goal of providing the foundation for translational work on, ultimately, interventions.”

References

Guangyu Zhou, Jonas K. Olofsson, Mohamad Z. Koubeissi, Georgios Menelaou, Joshua Rosenow, Stephan U. Schuele, Pengfei Xu, Joel L. Voss, Gregory Lane, Christina Zelano. “Human Hippocampal Connectivity Is Stronger in Olfaction Than Other Sensory Systems.” Progress in Neurobiology (First available online: February 25, 2021) DOI: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2021.102027

Source: Why Smells and Memories Are So Strongly Linked in Our Brains | Psychology Today