During an educational trip to India, members of the Centre for Genomic Gastronomy discovered that egg whites can absorb pollutants in the air. Centre for Genomic Gastronomy

The Smog Tasting Project delves into the causes of air pollution in specific areas, in a bid to make people think twice about their behaviour

Smog – we can see it and smell it, but can we taste it? Now, a team of artists have found a way to do so.

For years, the Centre for Genomic Gastronomy, founded by artists Zack Denfeld and Catherine Kramer, has been running the Smog Tasting Project and capturing the flavours of atmospheres in cities around the world.

London is a little gritty. Beijing, more sulfurous. Los Angeles has hints of bleach, while Atlanta smog owes its distinct flavour to a fusion of car exhausts and numerous nearby pine trees. These “tasting notes” have been distilled in the unlikeliest of foods: meringues.

For a recent exhibition in late 2019, the CGG worked with Hong Kong residents, turning them into “smog harvesters”, to prepare five different meringues from the autonomous area’s various neighbourhoods. Visitors sampled the sweets to compare how air pollution conditions in each area had affected the flavour of the dessert.

The secret of meringues

So how exactly could meringues reveal this? In 2011, Denfeld and Kramer made a discovery while teaching at the Srishti Institute of Art, Design and Technology in Bangalore, India. In discussions with their students, they searched for ways to address environmental pollution. “The students agreed that another screen that just showed numbers would not really change people’s beliefs or behaviours. So we turned our research interests to food and cooking,” he recalls.

During a workshop, they came across a passage in the book On Food and Cooking by Harold McGee, which stated: “Thanks to eggs we are able to harvest the air … at the ‘stiff peak’ stage … [egg] foam is approaching 90 per cent air.” That means when egg whites are beaten, their proteins begin to unfold and trap air in tiny bubbles, until the mix fluffs up into a thick foam. To prevent that egg foam from deflating, a stabiliser, such as sugar, can be added to the mix, turning it into batter for smog meringues.

The couple and their students hit the streets of Bangalore to test it out, whipping bowlfuls of egg whites on rooftops and roadsides before hurrying to the kitchen to prepare their dusty desserts. “One shouldn’t worry too much about getting sick from these cookies: we breathe this air every day!,” the CGG’s website says. The meringues can also be tested in a laboratory for the presence of heavy metals and pollutants, though this data has yet to be analysed by the centre.

“By using taste and flavour and using their bodies in a new way, people would actually start to see pollution differently” – Zack Denfeld, artist

Changing perceptions

Cities in India endure some of the worst air pollution in the world, with more than a million deaths attributed to poor air quality in the country. Worldwide, air pollution claims the lives of an estimated seven million people every year, according to the World Health Organisation.

“By using taste and flavour and using their bodies in a new way, people would actually start to see pollution differently,” Denfeld says. “We saw it had some real impact. People had all these questions, ‘why is it this taste?’, ‘what kind of pollution is it?’. It’s what encouraged us to do more research and go further.”

Since then, the Smog Tasting Project has undergone various iterations and has reached five continents.

The ongoing experimental endeavour is part conceptual art and part scientific research. It ties into the CGG’s mission of examining human food systems and biotechnology through art and design. The think tank collaborates with farmers, chefs, academics and designers to present exhibitions, lectures and publications on subjects such as the future of food.

In January, the team presented a different project called New National Dish: UAE at Quoz Arts Fest in Dubai. The exhibition looked at how the use of local ingredients, such as sea asparagus, camel milk and ghaf bark, could be expanded to maintain a more sustainable diet.

The Centre for Genomic Gastronomy’s smog synthesiser, which can recreate smog from different geographies and time periods. Courtesy Jordan Ralph Design

The taste of air in different times and territories

The Smog Tasting Project evolved in 2015 to include a smog synthesiser, which the CGG built with the help of advice from academics at the University of California, Riverside. The machine uses atmospheric process chambers to infuse egg whites with synthetic smog, formulated from specific geographies and time periods. An example is the London-style pea-souper smog, caused by the burning of coal to heat homes and that led to the transformation of the city into an industrial centre in the 1800s.

“As artists, as designers, we’re really trying to move beyond just metaphor and have something that’s materially there. So the fact that we can show people the chemicals and say, ‘Hey, this is how smog would have been in London in 1880 and Los Angeles in 1950’, it really allowed a more specific conversation,” Denfeld says.

Working with writer Nicola Twilley, the group developed the concept of “aerior”, an adaptation of the French term “terroir”, which looks at how soil, topography and climate affect the taste and flavour of wine. Twilley’s version applies to how air quality and elements in the atmosphere can have the same effect on agriculture and even street food.

The same year, the CGG’s smog synthesiser travelled to Paris for the United Nations Climate Change Conference, or COP21, and the team put together an exhibition with the WHO. They showcased the classic types of smog identified by atmospheric scientists, allowing visitors to smell and taste their differences. They showed that agricultural smog, for example, typically found at sites where pesticides and fertiliser are heavily used, had a sour smell and taste because of the ammonia. And in big cities that burn coal and have a high volume of motor vehicles, the skies are thick with sulfur and particulate matter, leading to an “acrid” and “gritty” taste, Denfeld says, with a smell that “could burn your throat”.

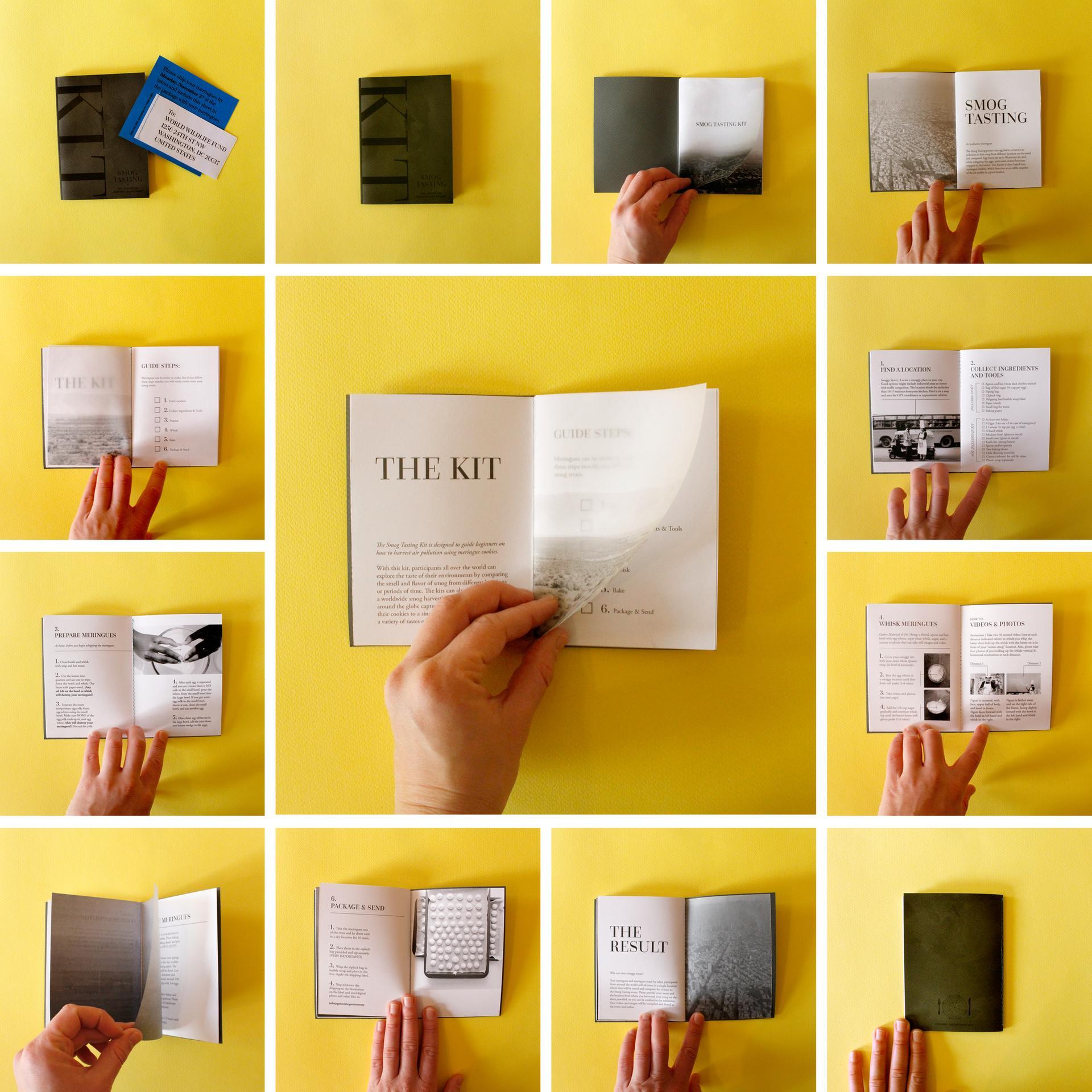

Two years later, the team developed Smog Tasting: Takeout, which expanded the project to several cities, including Mumbai, Perth, Washington, London, Beijing and Barcelona. The centre produced Smog Tasting kits with instructions for participants on baking their own smog meringues.

The centre’s Smog Tasting Kits guide participants on capturing their neighbourhood’s smog in meringue cookie batter. Courtesy Centre for Genomic Gastronomy

Individuals could then use it to trigger conversations about environmental pollution and air quality in their own communities. “One community organiser used it in her work to reduce the air pollution caused by a factory in her neighbourhood. She was staging different performances and activations in front of the property. In her research, she found that there was a longer history of this, of people combining food and air pollution,” Denfeld says. “So it’s not really about smog tasting, but getting people together around food and then directing energies towards what the issues are.”

In their research, the team and its collaborators consider how social and political events prompt changes in the quality of our land and air, as in the case of their recent show in Hong Kong, a place where the government fired more than 1,800 rounds of teargas to disperse pro-democracy protestors last year. The lingering effects of toxicity are still being studied.

It’s about art, not activism

Currently, Denfeld and Kramer are in Bergen, Norway, where they are expanding the project to compare pollution levels in various parts of the city and determining the reasons behind the dissimilarities.

The Smog Tasting Project is not meant to be rigorously scientific, and its exhibitions have not compelled direct policy change. Even Denfeld acknowledges this. “It’s more art than direct activism,” he says. Like art, it sometimes just helps turn your head towards a topic you have been overlooking.

“It’s really hard for people to deal with a planetary scale issue like climate change. Although climate and localised air pollution are obviously different problems, in many ways they overlap,” he says, adding that the goal of the project is to make people more active than passive when it comes to thinking about the air they breathe.

It is the same principle that has led to their latest work, Guided Smog Smelling, a three-part meditation series that asks people to “smell the new (ab)normal” as the lockdowns amid the pandemic have caused a sharp dip in air pollution.

Speaking of the Smog Tasting Project, Denfeld says, “It’s important to go actually go out there and look around your neighbourhood. You see it and smell it. It leads to more questions. It makes it concrete and real in terms of how you experience it, but also in terms of the facts that you can gather.” He adds that, if anything, whipping egg whites on the street is a sure conversation starter.

More information on the Smog Tasting Project is at www.genomicgastronomy.com