“What does labor smell like?”

Now, that’s a question that you probably never thought you would be asked, let alone attempt to figure out. Well, if the thought of coming up with the answer is too daunting, or weird, or gross, then award-winning University at Buffalo professor of art, Paul Vanouse, can help to guide you. His latest exhibit sets out to tackle the bizarre question, so that we all might stop to consider what a world without human labor might be like someday, as our own human labor force dwindles, as it is replaced by advanced technology.

Labor reflects industrial society’s shift from human and machine labor, to increasingly pervasive forms of microbial manufacturing.

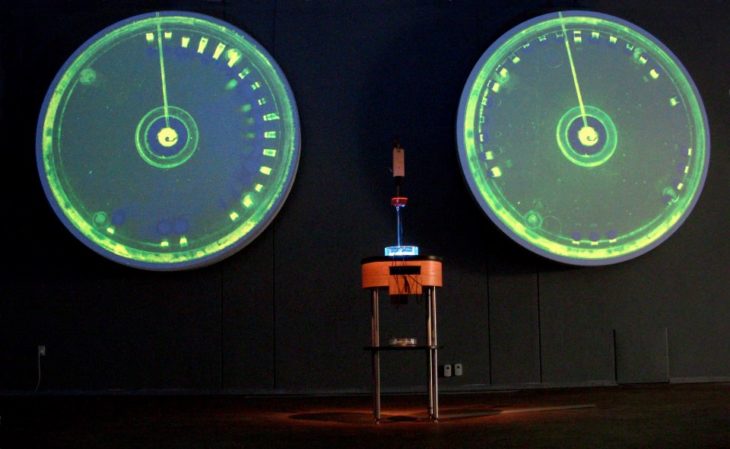

If you’re thinking that this exhibit will be a bunch of sweaty laborers standing around in a room, you’re wrong. It might smell that way, but the odors that you’re smelling will be “formed by bacteria procreating in three industrial fermenters in the middle of the Burchfield Art Center’s project space.”

According to Vanouse, who is also director of Coalesce: Center for Biological Art, and recipient of the Award of Distinction in Hybrid Art at the prestigious 2017 Prix Ars Electronica (a cyberarts global festival and competition), three 20-gallon industrial fermenters will be “cradled by temperature regulating units and motorized mixers connected to gas, nutrient and waste canisters by hoses.”

“Each fermenter incubates a unique species of human skin bacteria responsible for the primary scent of sweat: Staphylococcus epidermis, Coryne and Propionibacterium. As these bacteria digest simple sugars and fats, they create the distinct smells associated with human exertion, stress and anxiety. Their scents will combine in the central chamber in which a sweatshop icon, the white t-shirt, is infused as scents disseminate. This odor is expected to grow stronger throughout the exhibition.

Microbes in and on the human body vastly outnumber human cells and they help regulate many bodily processes, from digestive and immune systems to emotional and physiological responses like sweating.

“Today, microbes produce a wide range of products, including enzymes, foods, beverages, feedstocks, fuels and pharmaceuticals. They literally live to work. These new industrial processes point to a deepening exploitation of life and living processes: the design, engineering, management and commodification of life itself. In Labor, the microorganisms ironically produce the scent of sweat, not as a vulgar bi-product of production, like in factories of the 19th and 20th centuries, but as a nostalgic end-product.

“Our microbiota is integral to who and what we are, and complicates any simplistic sense of self. Likewise, the smell of the perspiring body is not just a human scent, unless we are willing to redefine what we mean by human?”

Paul Vanouse: Labor

On view Friday, January 11–Sunday, March 31, 2019

Researcher Solon Morse, Coalesce lab manager, is scientific collaborator on the project

Burchfield Penney Art Center | 1300 Elmwood Avenue | Buffalo, New York 14222 | (716) 878-6011

Lead image: BioArt-Kunst aus dem Labor