A LITTLE OVER a dozen years ago, “la merde… hit le ventilateur” in the world of wine.

Nobody remembers the 2001 winner of Amorim Academy’s annual competition to crown the greatest contribution to the science of wine (“a study of genetic polymorphism in the cultivated vine Vitis vinifera L. by means of microsatellite markers”), but many do recall the runner-up: a certain dissertation by Frédéric Brochet, then a PhD candidate at the University of Bordeaux II in Talence, France. His big finding lit a fire under the seats of wine snobs everywhere.

In a sneaky study, Brochet dyed a white wine red and gave it to 54 oenology (wine science) students. The supposedly expert panel overwhelmingly described the beverage like they would a red wine. They were completely fooled.

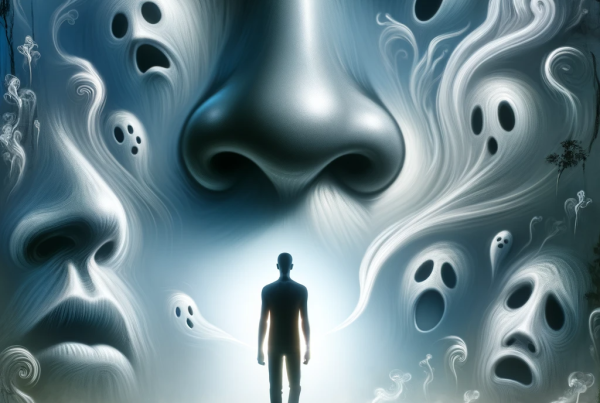

The research, later published in the journal Brain and Language, is now widely used to show why wine tasting is total BS. But more than that, the study says something fascinating about how we perceive the world around us: that visual cues can effectively override our senses of taste and smell (which are, of course, pretty much the same thing.)

WHEN BROCHET BEGAN his study, scientists already knew that the brain processes olfactory (taste and smell) cues approximately ten times slower than sight — 400 milliseconds versus 40 milliseconds. It’s likely that in the interest of evolutionary fitness, i.e. spotting a predator, the brain gradually developed to fast track visual information. Brochet’s research further demonstrated that, in the hierarchy of perception, vision clearly takes precedence.

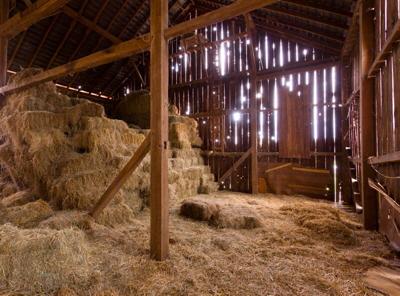

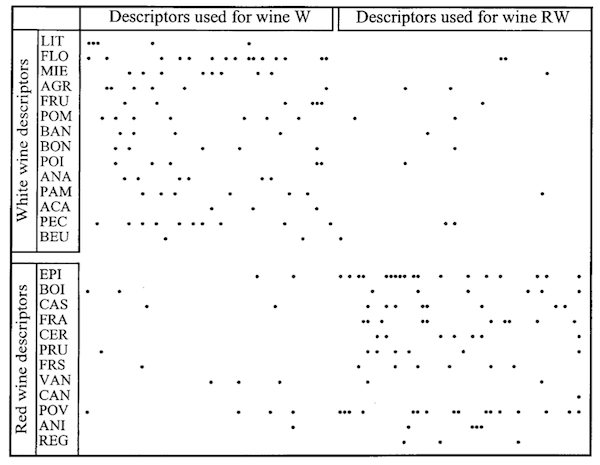

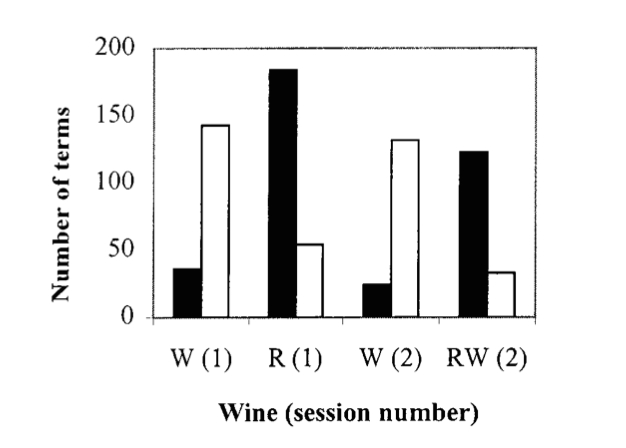

Here’s how the research went down. First, Brochet gave 27 male and 27 female oenology students a glass of red and a glass of white wine and asked them to describe the flavor of each. The students described the white with terms like “floral,” “honey,” “peach,” and “lemon.” The red elicited descriptions of “raspberry,” “cherry,” “cedar,” and “chicory.”

A week later, the students were invited back for another tasting session. Brochet again offered them a glass of red wine and a glass of white. But he deceived them. The two wines were actually the same white wine as before, but one was dyed with tasteless red food coloring. The white wine (W) was described similarly to how it was described in the first tasting. The white wine dyed red (RW), however, was described with the same terms commonly ascribed to a red wine.

“The wine’s color appears to provide significant sensory information, which misleads the subjects’ ability to judge flavor,” Brochet wrote of the results.

“The observed phenomenon is a real perceptual illusion,” he added. “The subjects smell the wine, make the conscious act of odor determination and verbalize their olfactory perception by using odor descriptors. However, the sensory and cognitive processes were mostly based on the wine color.”

Brochet also noted that, in general, descriptions of smell are almost entirely based on what we see.

“The fact that there are no specific terms to describe odors supports the idea of a defective association between odor and language. Odors take the name of the objects that have these odors.”

Now that’s deep. Something to ponder over your next glass of Merlot, perhaps?

A FEW YEARS after publishing his now famous paper, the amiable, bespectacled, and lean Brochet turned away from the unkind, meritocratic, and bloated culture of French academia and launched a career that blended his love for science and his passion for “creating stuff.”

Yep. You guessed it. He makes wine.

(Images: AP, Morrot, Brochet, and Dubourdieu)

Source: The Legendary Study That Embarrassed Wine Experts Across the Globe | RealClearScience