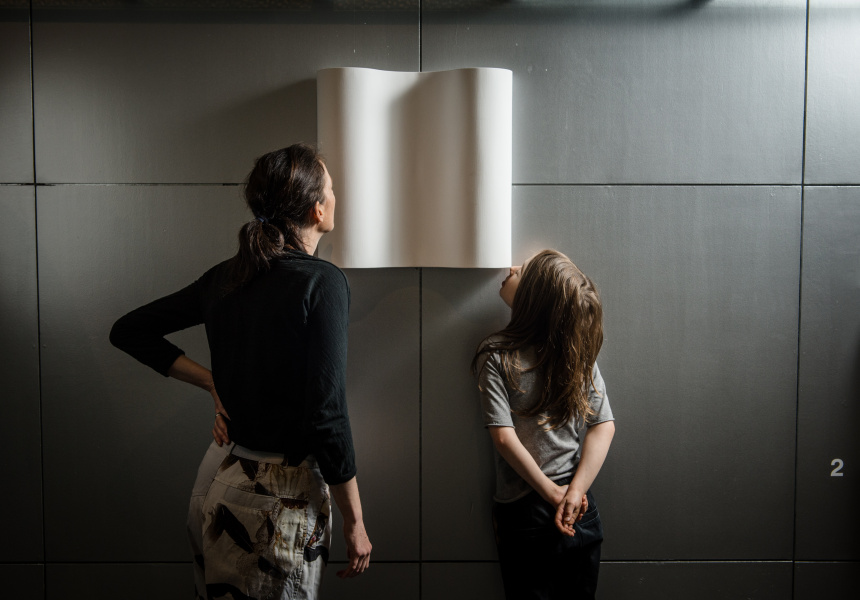

The NGV Triennial is filled with grand gestures and political statements; there are giant skulls, digital wave pools and large-scale filmic works shot on military-grade long-range cameras. Sissel Tolaas’s work is more subtle but it’s one of the most innovative – and surprising – pieces in the whole show. It’s a series of small, white, abstract sculptures equally spaced across four walls. These sculptures hide secrets. Each is imbued with scent, which triggers a memory or a feeling or, sometimes, an acute physical reaction.

“I display it as a memory game,” Tolaas says as we wander around the installation sniffing her work. “On this [wall] there are five smells. They repeat on the other side. I want people to try to match them.”

Tolaas is vivacious, hilarious and passionate about scent. During our meeting at the NGV she’s frequently distracted by kids enjoying her work. Many identify the scents in no time while their parents struggle. Kids are still in touch with their senses, Tolaas says; adults have disengaged.

She tests me. I manage to pick a couple of the smells with a bit of help. The first is dry earth after a fire. It brings back memories of camping and distant bushfires. The second is a wet animal. It’s extraordinary the feelings these pieces conjure, unlocking memories and associations that would otherwise lay dormant.

Everybody breathes. We inhale 24,000 times a day and inhale smell molecules in every breath. It’s through our olfactory sense we detect hazards, food and pheromones. Our individual smell identities are as unique as our fingerprints. So why do we never talk about it? And why do we drown out our natural odour – and others’ – with perfume?

“Mostly due to lack of education, and lack of language,” Tolaas says. “We don’t have the words.

She compares it to music. We have a whole language around how we hear music, including standard notation, technical understandings of why something sounds good or bad, and a broad culture of different styles and interpretations. Not so with smell.

In her native Norway there are more words for “smells” than here (Norwegians also have more words for different kinds of wind and snow and rain). But English is relatively impoverished.

“There’s also an industry very happy to cover up the reality of scent,” Tolaas adds. “I’m talking about things like fragrance and detergent. It’s not easy to get past that.”

The abstract forms in her Triennial “smellscape” – and the emotions they evoke – come out of extensive research, chemical processing and nanotechnology. Tolaas has a PhD in chemistry and this work – part of an ongoing project with the University of Melbourne – is based on an interrogation of Melbourne’s scent, looking at smell sources past and present. Tolaas consulted with historians, anthropologists, ethnologists, social scientists and other experts to create the work, and these 20 smells took a year to formulate.

In the past she’s created works that reconstruct the smells of Central Park in New York, the city of Istanbul, and World War One. She’s worked for commercial clients including Adidas, Volvo and designer labels such as Prada and Maison Martin Margiela.

Out in the field, Tolaas uses a device she describes as looking like a tiny vacuum cleaner. She collects samples and analyses them, breaking their smells down into molecules. Her Berlin lab has more than 6000 chemical compounds, which she uses to replicate a scent discovered in her fieldwork. It’s a rigorous and time-consuming process.

For the Melbourne installation, Tolaas has recreated historical smells from pre-colonial times up to the present day; it’s about connection to the land through our most immediate sense.

“It’s an attempt to engage with history in an emotional way,” says Tolaas. “Smell is the quickest and most efficient way to trigger memory and emotion.”

The first time you smell something, she says, it’s associated with the context in which you smell it. That association stays with you until you die.

Tolaas travels the world advocating for scent education. She laughs that she was once arrested in Cape Town as she walked around with her device capturing scents. She must have looked strange wandering the city smelling things and taking samples, so someone called the cops.

The scents embedded in these sculptures will last seven years. Across that time they’ll gain layers of information from people touching and interacting with them. So after a few months on the wall the original may have morphed into something different. But that’s what history is about.

I lean in to one more sculpture. It’s familiar, but I can’t quite pick it.

Tolaas nods encouragingly.

“You’ve got it, I think,” she says.

“Is it horse shit?”

She claps and grins. “Close,” she says. “Dog shit and garbage!”

Source: Smelling Art with Sissel Tolaas