Should anything ever compel you to lick an octopus’s arm, keep this in mind: That arm has all the cellular machinery to taste your tongue right back.

Scientists have known for years that octopuses can taste what their arms touch. Now, a team of Harvard biologists armed with bricks, Velcro and an array of genetic tools has cracked some of the code behind this feel-and-feed feat.

The cells of octopus suckers are decorated with a mixture of tiny detector proteins. Each type of sensor responds to a distinct chemical cue, giving the animals an extraordinarily refined palate that can inform how their agile arms react, jettisoning an object as useless or dangerous, or nabbing it for a snack.

The study, published Thursday in the journal Cell, “really nails the molecular basis for a new sensory system,” said Rebecca Tarvin, a biologist at the University of California, Berkeley, who wrote a commentary on the findings but was not involved in the research. “This was previously kind of a black box.”

Though humans have nothing quite comparable in their anatomy, being an octopus might be roughly akin to exploring the world with eight giant, sucker-studded tongues, said Lena van Giesen, the study’s lead author. “Or maybe it feels totally different,” she said. “We just don’t know.”

The internal architecture of an octopus is as labyrinthine as it is bizarre. Nestled inside each body are three hearts, a parrot-like beak and, arguably, nine “brains” — a central hub with an octo-entourage of nerve cell clusters, one in each of the animal’s eight arms. Imbued with their own neurons, octopus arms can act semi-autonomously, gathering and exchanging information without routing it through the main brain. (Even after amputation, these adept appendages can still snatch hungrily at morsels of food.)

Octopuses certainly know how to put that processing power to good use. Scientists have found the cephalopods can wield tools, puzzle their way through mazes and mischievously squirt water at their caretakers. Housed in labs, they’ll also try to liberate themselves from their tanks, unless the lids are weighted down with bricks and lined with Velcro — a textured material that the animals apparently dislike, said Nicholas Bellono, a co-author of the study.

But many of the fine details that underlie octopus behavior remain mysterious. It’s long been unclear, for instance, how the animals, just by probing their surroundings with their limbs, can distinguish something like a crab from a less edible object.

In the lab, Dr. van Giesen, Dr. Bellono and their team studied cells extracted from suckers on the arms of California two-spot octopuses, a melon-size species native to the Pacific Ocean.

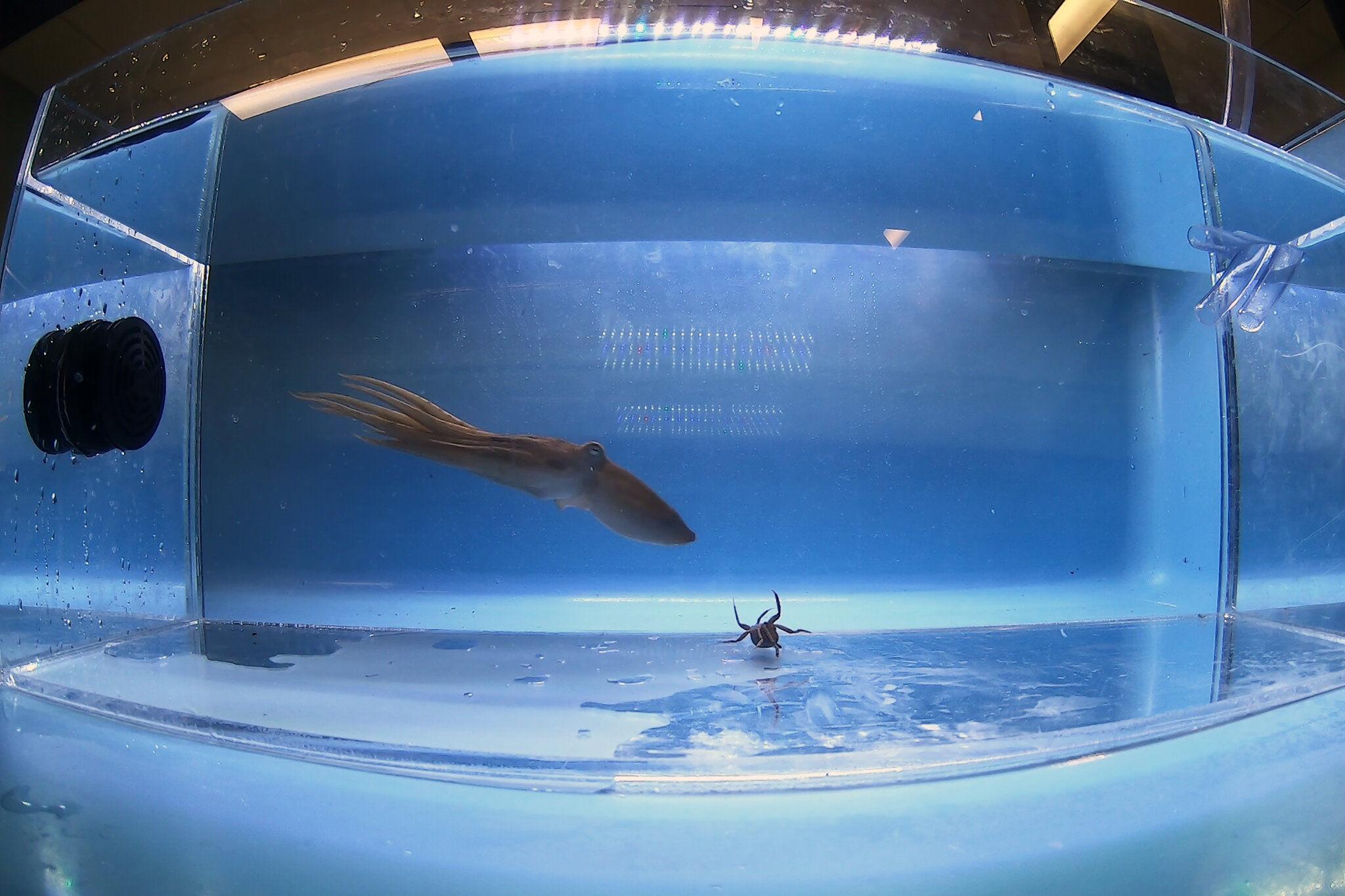

Video by Peter Kilian

Video by Peter KilianSome cells, they discovered, were there to detect only touch, and responded to pressure. Another population of cells, called chemoreceptors, instead detected chemicals, such as those that imbued fish with flavor.

A series of genetic experiments then revealed that the surfaces of these taste-tuned cells were covered with different types of proteins, each tailored to its own chemical trigger. By mixing and matching these proteins, cells could develop their own unique tasting profiles, allowing the octopus’s suckers to discern flavors in fine gradations, then shoot the sensation to other parts of the nervous system.

It seems octopuses have “a very detailed taste map of what they’re touching,” Dr. Tarvin said. “They don’t even need to see it. They’re just responding to attractive and aversive compounds.”

Underwater, some chemicals can travel far from their source, making it possible for some creatures to catch a whiff of their prey from afar. But for chemicals that don’t move through the ocean easily, a touch-taste strategy is handy, Dr. Bellono said.

Discerning though it may be, the octopus palate hasn’t made these animals terribly picky. They eat fish, crabs, snails, other octopuses — “everything they can find, really,” Dr. van Giesen said. “They are voracious.”

The researchers weren’t able to investigate every chemical-sensing protein that played a role in octopus touch-taste tactics. But they found that some of the cells in the animal’s suckers would shut down when exposed to octopus ink, which is sometimes released as a “warning signal,” Dr. van Giesen said. “Maybe there is some kind of filtering of information that is important for the animal in specific situations,” like when danger is afoot, she said.

Humans, who tend to be very visual creatures, probably can’t fully appreciate the sensory nuances of a taste-sensitive arm, said Paloma Gonzalez Bellido, a biologist at the University of Minnesota who wasn’t involved in the study. But that’s all the more reason to study cephalopods, she said.

“Sometimes we assume in neuroscience or animal behavior, there’s only one way of doing it,” Dr. Gonzalez Bellido said.

In the dark, complex environments they navigate, octopuses certainly have a leg up (or eight) on their distant landlubbing relatives. But then again, most people could probably do without the metallic tang of keys every time they rummage in their pockets — or the funk that would inevitably dissuade every new parent from changing a diaper.

“I think if we had that ability,” Dr. Tarvin said, “we’d probably choose to wear gloves some of the time.”