When considering the testing processes in food production, most minds will gravitate to laboratory analysis. Here, we find out about another important test – sensory experience and fulfilment – and how it can make or break a product.

Everyone reading this will know that eating is a multi-sensory experience. It is the onslaught of visuals, smell, taste, sound, texture and trigeminal stimulation that creates the flavours and textures of the foods and drinks that we love …and it is also the reason that we don’t like others so much!

Unfortunately for food manufacturers, people are humans and not machines, and consequently they vary enormously, not only in the intensity of the sensations they perceive, but also the qualities they notice and their preference for them. We are alert to the flavour notes we don’t like and react more strongly to the textures we associate with unpleasant childhood food experiences.

As individuals, the consistency of our perceptions also varies. One of the greatest influencers of all is attention: if we are not paying attention to what we are eating, we won’t perceive very much. But environment and mood also play a huge role. The Provencal Rosé Paradox1 explains how a rosé wine that tasted so delicious in the warm French sunshine tastes cheap, sour and vinegary on a wet February evening in England. Of course, the wine itself is the same, but the changes in environment and your emotional state have changed your experience of the wine.

How to be first to market with innovative products

In today’s fierce market innovation and speed are top priorities. Join us as we hear from Trace One about how businesses can balance the two.

You will also be able to ask our expert speaker Don Low, Solutions Consultant, Trace One questions during the Q&A session at the end of the presentation.

Our senses interact with our past experiences to create an expectation of what a food will taste like. This can lead to a positive or poor experience depending on how the product performs against this expectation. We learn from childhood that red liquids are perceived as sweet and strawberry flavoured, even if they are actually acidic and taste of lime. Similarly, if we see white ‘meat’ pieces in a meat-free pie, we are primed to expect the taste and texture of chicken. We will be let down if the experiences we anticipate don’t match up.

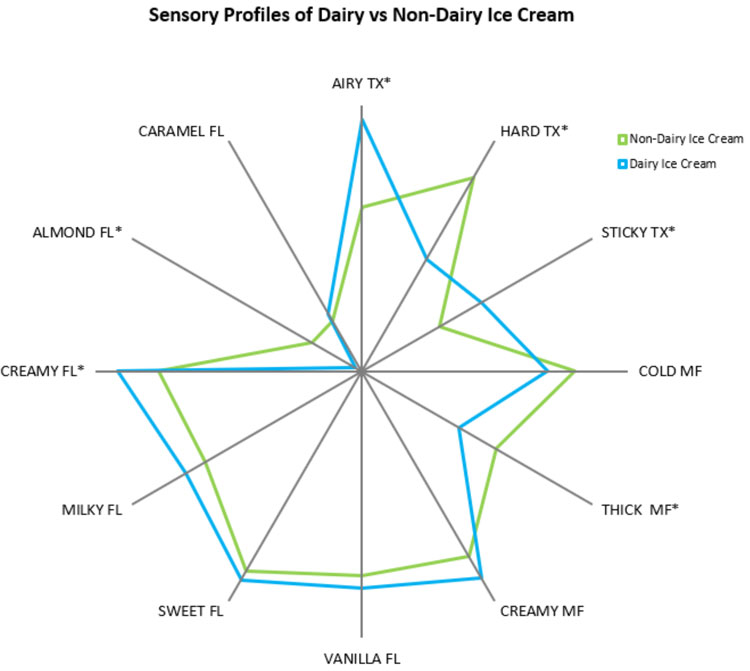

Figure 1: Sensory results are presented visually in a diagram such as the one above

In foods, expectation is strongly primed by brand, our previous product experience, packaging, and by our judgment of value. If you have eaten a product before, you expect the same experience, so it is essential that it delivers against your key criteria every time (ie, it’s consistent). Changing product formulation for cost reasons or to comply with regulations, such as HFSS (high in fats, sugar and salt), therefore requires extreme care on the manufacturer’s part to maintain the consistency of the consumer experience.

Trained sensory panels are traditionally used to monitor the impact of recipe and process changes on the product. A sensory panel is a group of 10-12 people, selected based on slightly higher-than-average sensory acuity coupled with an ability to describe what they perceive. These abilities are tested via a series of screening taste tests. The group is then trained to improve and unify its descriptive language and to rate the intensity of sensory attributes consistently.

Panels often use a technique called ‘descriptive sensory profiling’ to break down the product experience into its component parts and measure the intensity of each. For example, the flavour of an ice cream may comprise vanilla, sweet, milk, cream, caramel and almond notes. Comparing the intensity of these notes across recipes pinpoints differences created by varying the type and level of ingredients. The results are analysed statistically and often presented visually as spider profile diagrams (see Figure 1).

Sensory panels traditionally focus on the eating experience, work in standardised sensory laboratories (see Figure 2) and eat pre-prepared and pre-portioned product that is presented blind-coded. The limitation with this is that it doesn’t include the product use experience and, as discussed above, we know that consumer reaction to a product depends upon more than just the eating. It follows, therefore, that extending the scope of the sensory panel to make objective measures of the holistic product experience will add real insight to the motivations behind purchase and repeat purchase.

Figure 2: Sensory panels traditionally focus on the eating experience working in standardised sensory laboratories

For this reason, in addition to in-lab testing, Sensory Dimensions’ panels are also using their descriptive and measurement skills while they prepare and eat products in-home in the normal way. We are using smart speaker technology to collect these in-home data.

The ultimate judge is, of course, the consumer; robust consumer product testing research is an essential step for validation of product modifications.

The real magic lies in using objective sensory data to identify what drives product likeability. Approaches such as SD’s OptiMap+ bring together data from consumers about their preferences with sensory panel data centring on the experience of eating those products (consumers are not very good at explaining why they like or dislike things).

The outcome? Identification of the sensory characteristics that drive likability and which should be avoided. The action? Strategic formulation to optimise the sensory experience of your product for success in the marketplace.

About the author

Tracey Sanderson is Managing Director at Sensory Dimensions Ltd, a sensory and consumer research consultancy working with clients across the food and beverage industries, to help them create successful products and maximise their competitive advantage.

Reference

- Russell Jones, Sense, 2020, Wellbeck