David Hale doesn’t know whether his poem will kill the culture.

It’s not that “Affliction 11” is a bad poem. It’s a beautiful one, a brief, subtle meditation on the transmission of belief, filtered through the 32-year-old’s experiences at a Catholic university. But now that the poem’s 309 characters have been assigned their accompanying letter-coded amino acids, which were then coded into RNA, which was then coded into DNA and inserted into E. coli, Hale doesn’t know what will happen if he splices in the genetic code that will let the biological, poetic virus culture sitting in the freezer of his San Antonio apartment replicate and grow.

“It itself could be toxic,” he says. “Or maybe it doesn’t do anything. Or maybe it does something weird, like it grows hair.”

Oppman’s goal is to see whether the 2013 Supreme Court case Association for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics, Inc., actually ended the 25-year practice of gene patenting—that is, for-profit labs identifying and claiming human genes as intellectual property in order to profit from any medicines or treatment derived from studying those genes.

“Part trying to raise awareness and explain this to my peers and part trying to really see what I can get away with, I am trying to do the slightest mutation possible so I can say that I tweaked this gene just enough that it’s now my intellectual property,” Oppman explains. “But hopefully the gene will still function as normal.”

Oppman, who came to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago to study sculpture, decided to work with the brain-derived neurotrophic factor gene, which helps create a protein found in our brains and spines. They then identified the noncoding RNA, identified a sequence that was part of the gene but not the coding sequence, designed primers to amplify a region of the sequence, purified their DNA with Chelex 100, performed a polymerase chain reaction, and put it in gel.

Once they have their DNA growing in a bacterial plasmid—a small DNA molecule that can replicate independently of the rest of the DNA in the same cell—the process of mutating it starts. There are several options for mutating the sample; Oppman is currently leaning toward exposing it to UV light. Their goal is to find the smallest mutation that a patent lawyer can turn into a design or utility patent, which Oppman considers a loophole in Myriad.

Oppman and Hale, and also the student distilling the essence of gym socks, the student growing a mask out of mushrooms, and the student collaborating on a song with the yeast from her sourdough starter have all done their work at SAIC’s Bio Art Lab. Down in the basement of the MacLean Center at 112 S. Michigan, they use test tubes, beakers, microscopes, centrifuges, fungi, bacteria, and worms to create art that, quite literally, is alive.

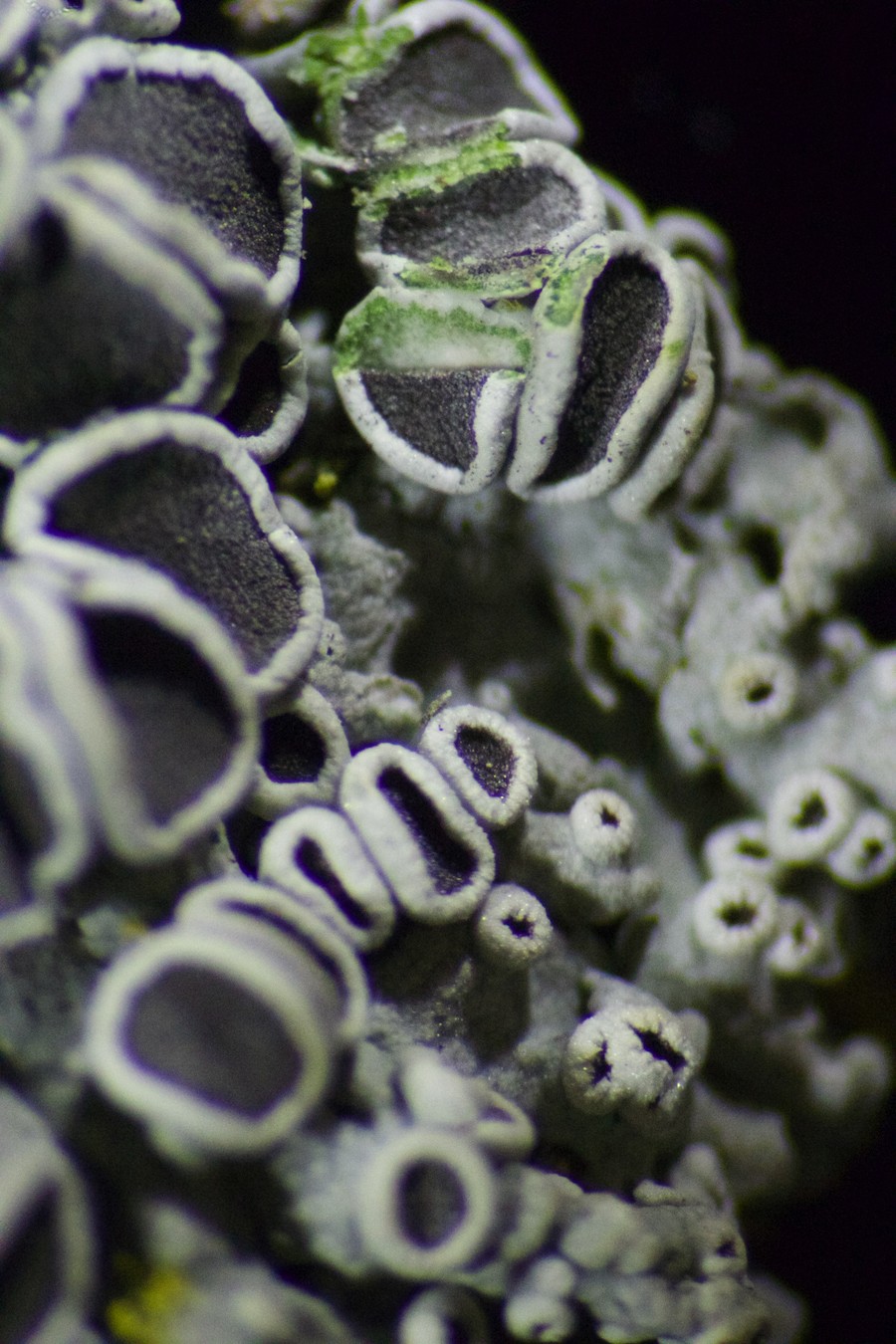

- Lichen

- ANDREW SCARPELLI

“Don’t Open Those”

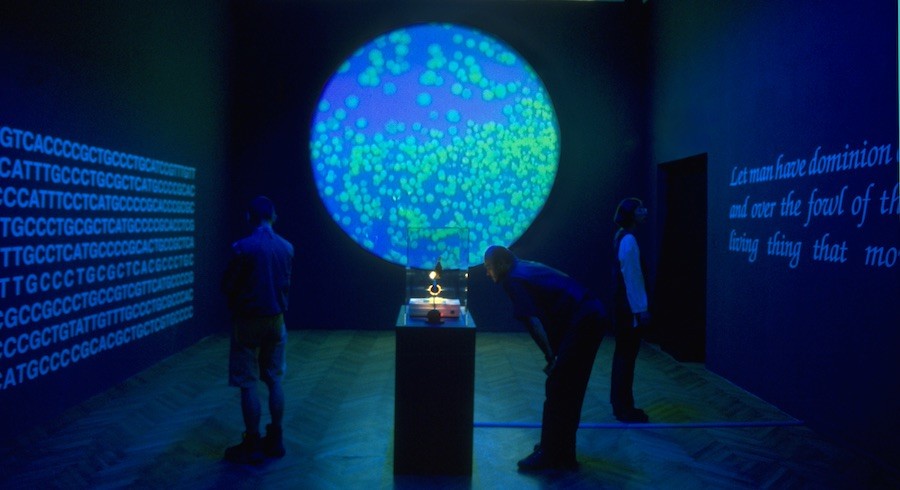

Department of Art and Technology Studies professor Eduardo Kac and grad student Yutaka Makino first opened a bio lab for research, not classes, on the MacLean Center’s fourth floor in 2003.

“It was a very, very small kind of tiny space—basically a closet,” recalls Anna Yu, the department’s assistant director of facilities.

That lab shuttered in 2004 so the valuable space in the gallery-packed campus could be used to fabricate surface-mount circuit boards. Bio art seminars continued, showing students the work being done in the field, but there was no lab where students could dive in and create their own living art. Kac had to wait 10 years before the perfect spot became available.

“Life is supple and also very resilient, but the one thing that we know that life cannot exist without is water,” Kac says.

In other words, they needed a sink.

The current facility—with an industrial sink—opened in the basement in 2014. It’s a biosafety level 1 lab. The highest biosafety level is 4, at which Ebola, Kyasanur Forest disease, Marburg, and other potential pandemics are studied. A level 1 lab like SAIC’s is similar to what one might find at a community college or a particularly well-funded high school, according to the Federation of American Scientists. The biosafety levels set security protocols (whether you need a hazmat suit or can eat your lunch in the lab) and also limits on what materials a lab can work with, from DNA strands to individual cells to multicellular organisms like living animals.

“We can do multicellular organisms. We don’t,” says Bio Art studio and Critical Genetics lecturer Andrew Scarpelli, who is also a molecular biologist. “We don’t have an ethical review board, so we don’t do anything with animals. But if we wanted to [study multicellular organisms], it’s just human cells are out of line and certain unsafe microorganisms. For instance, certain strains of Yersinia pestis that caused the [bubonic] plague would be allowed here as long as they’re not deemed dangerous to people, but if there’s any that could cause disease, those would be banned.”

That’s a hypothetical—there’s no Yersinia pestis in the lab. But there are plastic containers full of dirt and earthworms used to compost. There are wonky cat masks, cuddly teddy bears, road cones, and pillows, all grown from mycelium (that’s mushrooms to us). And there’s a metal locker filled with vials from the olfactory art class that also meets in the room. The names scribbled on the vials include “Big Sur,” “Magenta,” “Meadow,” and “Gym Socks.”

“It is a lot worse than you can possibly imagine,” Scarpelli says of the distilled essence of sock. “When it starts to degrade, it’s this very acrid thing that just eats the back of your throat. Don’t open those.”

Scarpelli and lab coordinator Lynika Strozier are the scientists among the artists.

In May of this year, Strozier, 34, received her master’s degree in biology from Loyola University Chicago and her master’s degree in science education from UIC. With 12 years of research experience and what she describes as a dedicated personality—”I eat, breathe, sleep science,” she said—she soon parlayed her education into a research position at Rush University Medical Center.

It wasn’t a good fit. She arrived at the SAIC lab in August.

“I think what drew me to this position, I would be doing a little bit of everything,” she says. “It wasn’t just focusing on streak plating and isolating colonies and doing that same thing over and over again. After a while it becomes very repetitive, it becomes very annoying.”

Scarpelli, who received his Ph.D. from Northwestern and has expertise in microbiology and synthetic biology, says his goal is to give the artists the science they need to make their ideas happen, whether it’s burying a polylactic acid toy boat in worms and dirt to see if PLA plastic is as biodegradable as believed or it’s helping one of the three current students trying to get different microorganisms—slime mold, yeast, and bacteria, respectively—to write music by converting their chemical signals into MIDI files.

“The Bio Art course as it currently is right now is that the first eight weeks become this giant crash course in all sorts of different biology,” he says, “just because we have some students who want to work on human genetics and then other students who want to work on sculpting like topiary or bonsai, and then some students who want to work on something purely bacterial.”

It’s often a starting point for projects the artists will continue on their own, Scarpelli says, either because of graduation or other reasons. For example, the type of DNA work required for the next step of Oppman’s self-patenting project will require a biosafety level 2 lab.

Outside the lab, Scarpelli is one of the founders and lead organizers of ChiTownBio, a 501(c)(3) biotechnology meet-up. Eventually hoping to open a community biolab like New York’s Genspace or Silicon Valley’s BioCurious, the group holds events like biotech book clubs, barroom lectures on and playing with slime molds, enzymes, and strawberry DNA, and the yearly Bacterial Art Holiday Spectacular, held tonight at the Empirical Taproom, where attendees paint glowing E. colireindeer, Christmas trees, bacteriophage viruses, and dreidels.

“What’s great about [the SAIC program],” Scarpelli says, “is that artists have a great enthusiasm, and it’s really just being here as a biologist to match up what they do with the right language.”

- Eduina

- EDUARDO KAC

Ethics and Ethyls

The Bio Art Lab is part of SAIC’s Art and Technology Studies department. Starting in 1969 as the Kinetics area, “Art and Tech,” as Yu, Kac, and the faculty call it, has evolved into a catchall wonkaverse for media that don’t quite fit into painting, sculpture, or the rest of SAIC’s more traditional offerings

One of Art and Tech’s basement rooms holds what Yu called “retrotech”—Apple IIes, eight-inch floppies, Atari cartridges, and oscilloscopes. Students either use the tech to create new art or for “media archeology,” preserving old art created at the time when a Commodore 64 was the most bleeding of edge. It’s next to the Light Lab, where students with blowtorches in hands and breathing tubes in mouths melt and shape glass rods, making sure to blow into the tube so the hot glass doesn’t collapse on itself before krypton, argon, or neon can be pumped into it and lit up. Next comes the Kinetics Lab, one of the nation’s oldest facilities for teaching art students how to build and use mechatronics: whirling gears, chains, motors, rotors, and sundry doodads that make artwork dance like clockwork.

Kac created the term “bio art” in 1997. He’d been creating digital art since 1982 and working online since 1985, transmitting graphics through the French network and Internet precursor Minitel. By the 1990s, he wanted a term to separate the kind of art he wanted to develop from what he called the “frenzy” around the then-newfangled Internet craze.

“There was a lot of, in my view, nonsensical discourse around the web,” Kac says, “people talking about uploading their consciousness online and things like that.”

Since then, the Brazilian-born artist has used the banner of bio art and, later, transgenics, which he defines as the transfer of synthetic or natural genes between organisms, to install a computer chip inside his body (Time Capsule, 1997), translate a Bible verse into Morse code and from there into DNA base pairs (Genesis, 1999), and implant his genetic code into a petunia he calls “Eduina” (Natural History of the Enigma, 2003-08). In 2017, Kac and five other practicing bio artists wrote “What Bio Art Is: A Manifesto,” a mission statement for the medium, containing such directives as “All art materials have ethical implications, but they are most pressing when the media are alive.”

“This is more of a renewal of vows, if you will,” Kac says. “It was written deliberately, consciously, 20 years after the fact by the founders of the movement.”

Hale, who came to SAIC for the writing program, had long been interested in taking “words off of the page,” with past projects including projecting his poems on a wall. He wanted to explore what a poem is when separated from the ink on a page or the pixels on a screen. He had a chance not to write on college rule or iPad, but on the stuff of life, and he took it.

Much of his effort, he said, was writing a poem good enough to be worthy of the medium. Writers talk about breathing life into their words. Hale had to come up with words to breathe into life.

Kac understands.

“It’s humbling to work with life,” Kac says. “Life is absolutely incredible and marvelous, and the more we believe we know, the more amazing and incredible life becomes.”

But why work in bio art at all? Why sculpt in mushrooms and paint in slime mold? Why write poems in DNA instead of on paper? The answers are as varied as the reasons students a few floors above work in paint. Picasso had different motives than Bob Ross.

The cat masks and teddy bears grown of mycelium are cute but also train future makers in the use of what Scarpelli calls “a really nice futuristic packaging material” and insulator that could be used to replace Styrofoam. The compost worms show the artists which supposedly biodegradable materials actually biodegrade, and how quickly. Starting with the inaugural contest in 2016, Bio Art Lab students have competed in the yearly Biodesign Challenge, an international competition among colleges and universities around the planet to find biotech solutions to social issues, submitting ideas like a startup that converts used diapers into fertilizer and a prototype “living bathhouse” that (hypothetically) recycles the waters of California’s Mono Lake.

There are no prerequisite courses and it’s not part of any particular program, although Bio Art Lab is one of the courses recommended for students interested in studying Sustainable Design.

“The Fine Arts program is very open. You can be a photographer one year and you can be a sculptor the next year. You can just move around and take whatever you want,” Yu says. “The bio art curriculum in terms of Art and Tech, you don’t have to have any [science] background. You can just decide ‘I want to make something that I just thought up.'”

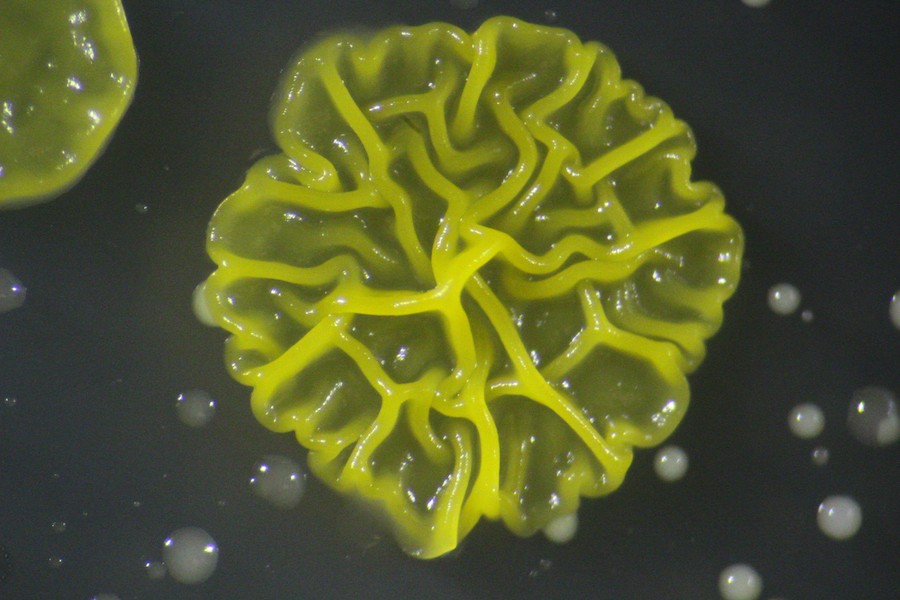

- Bacterial colony

- ANDREW SCARPELLI

—phenylalanine isoleucine asparagine—

But back to the question that may have been bothering you since the first line of this story: How do you put a poem inside E. coli?

Each of the 20 amino acids has a corresponding single-letter database code biologists have used for decades to standardize communication. Phenylalanine, which is found in breast milk and NutraSweet, is F. Tryptophan, which helps adults balance nitrogen content and, despite constant Thanksgiving assertions, does not actually make you sleepy, is W.

Each amino acid also has a corresponding DNA codon, a three-letter combination made up of A, T, G, or C to symbolize the four nucleobases that make up DNA: adenine, thymine, guanine, and cytosine.

So “M,” the first letter of “Affliction 11,” becomes methionine, which becomes ATG, which becomes adenine joined to thymine joined to guanine in the possibly toxic, possibly hairy poem in Hale’s freezer.

One of the first hurdles was linguistic rather than chemical. There are 26 letters in the alphabet but only 20 amino acid codes, meaning Hale’s bijou, expressive stanza couldn’t use the letters B, J, O, U, X, or Z.

“I couldn’t put the title in,” he says, laughing.

His project is on hold since his May 2017 graduation, since funding comes more easily to a project living in SAIC’s Bio Art Lab than in a Texas poet’s freezer. Catching funding as he can, Hale’s next goal is to code for bioluminescence so each strand of E. coli in the sample starts to glow as “Affliction 11” infects it.

His poem about the transmission of faith through human culture will spread through a bacterial culture, leaving a deep, internal glow on all it touches.

Or it will kill everything. Or make it grow hair.

Lights like palliating glimmer

A wish masks

A prayer

Distilled

As epithet

In epidemic’s wake

That’s the end of a poem written in the language of life itself. v

Source: Inside SAIC’s Bio Art Lab, where art is life—literally