Which do you find easier to describe: the colour of grass, or its smell? The answer may depend on where you are from – and, more specifically, which language you grew up speaking.

Humans are often characterised as visual beings. If you are a native English speaker, you may intuitively agree. After all, English has a rich vocabulary for colours and geometric shapes, but few words for smells. However, a recent global study suggests that whether we mainly experience the world by seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting or feeling varies hugely across cultures. And this preference is reflected in our language.

The study was based on tests conducted by 26 researchers across 20 languages in Europe, North and South America, Asia, Africa and Australia, with locations ranging from big modern cities to remote indigenous villages. Participants were asked to describe so-called sensory stimulants, such as coloured paper, a sip of sugar water, or a sniff of a scented card.

The results suggest that our lifestyle, our environment and even the shape of our houses all can influence how we perceive things – and how easy (or not) we find it to put this perception into words.

“I think we often think about language as giving us direct information about the world,” says Asifa Majid, a professor of language, communication, and cultural cognition at the University of York, who led the research. “You can see that in how we think about the senses and how that’s reflected in modern-day science.”

Majid says that many textbooks for example refer to humans as visual creatures.

“Part of the rationale for that has been the amount of brain that’s devoted to vision versus smell, for example. But another piece of crucial evidence has been language. So often people say, well, look, there are just many more words to talk about things that we see, and we struggle to talk about things that we smell,” she says.

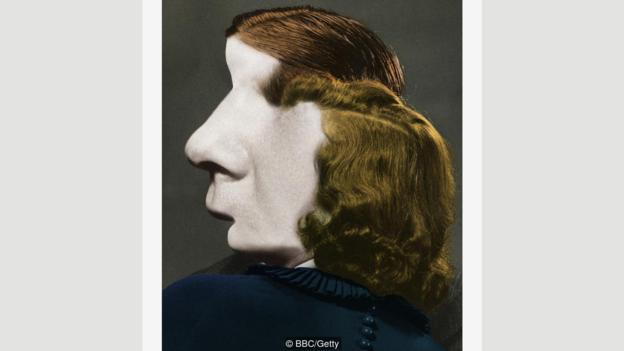

English speakers tend to struggle to talk about smells – but speakers of other languages do not (Credit: BBC/Getty)

However, Majid says some societies are much more oriented towards smell or sound. Her own research on the Jahai, a community of hunter-gatherers in the Malay Peninsula, has recorded a vocabulary for smells as varied and precise as the English vocabulary for colours.

The study brought together specialists in languages as diverse as Umpila, spoken by only about 100 people in Australia, to English, spoken by about a billion people around the world. In total, 313 people were tested. The researchers gave them the different stimulants, and then measured each group’s level of “codability” – that is, the level of agreement among the responses in each group. A high level of codability means that a group has an agreed-upon way of talking about, say, certain colours. A low level of codability can indicate that the group does not have a shared, commonly accepted vocabulary for those colours, or that it is unable to identify them.

English speakers were best at talking about shapes and colours. They all agreed, for example, that something was a triangle, or green.

Speakers of Lao and Farsi, on the other hand, excelled at naming tastes. When offered bitter-flavoured water, all Farsi speakers in the study described it as “talkh”, the Farsi word for bitter.

This was not the case with English speakers. When offered the same bitter-flavoured water, “English speakers said everything from bitter, to salty, sour, not bad, plain, mint, like ear wax, medicinal and so forth”, says Majid.

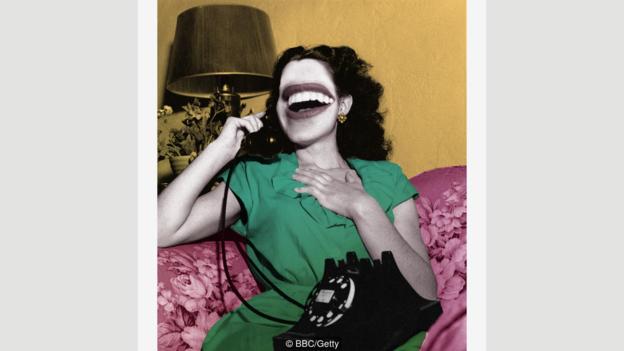

English speakers struggled to name tastes, while speakers of Lao and Farsi excelled (Credit: BBC/Getty)

She says this kind of taste confusion consistently happens to English speakers in lab tests: “They describe bitter as being salty and sour, they describe sour as being bitter, they describe salt as being sour. So even though we’ve got the vocabulary, there seems to be some confusion in people’s minds over how to map their taste experience onto language.”

Interestingly, the language communities that had very high scores for the tasting task – Farsi, Lao and Cantonese – all have famously sophisticated cuisines that cultivate a range of different flavours, including bitterness.

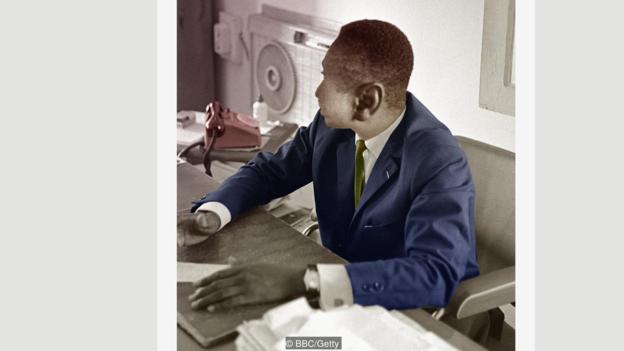

Other participants struggled with certain tasks because their language simply lacked words for what they were shown. Umpila, a language spoken by a hunter-gatherer community in Australia, only has words for black, white and red. However, Umpila speakers found it easiest to describe smells. This tendency towards smell rather than vision is found among hunter gatherers around the world, including the aforementioned Jahai. The reason may have to do with living and hunting in forests that are rich in smells.

The tendency towards smell rather than vision is found among hunter gatherers around the world (Credit: BBC/Getty)

The sensory diversity even held true across sign languages. Speakers of Kata Kolok, a village sign language spoken by about 1,200 people in Bali, struggled almost as much as the Umpila with describing colours. Speakers of American Sign Language and British Sign Language, on the other hand, found this task relatively easy, and scored about the same as English speakers.

Cultural factors from art to architecture appeared to play a role in how well participants performed across the different tests. People from communities that produced patterned pottery did better at talking about shapes. Those living in angular rather than round houses tended to be better at describing angular shapes. And participants from communities with specialist musicians were better at describing sounds – even though they were not musicians themselves.

“Just having specialist musicians means that that community develops a certain way of talking about sounds, and that everybody seems to have a better handle on how to talk about sounds,” Majid says.

Participants from communities with specialist musicians were better at describing sounds – even if they weren’t musicians themselves (Credit: BBC/Getty)

For those of us who spend more time in front of silent, odourless screens than among fragrant plants and jamming musicians, the study could be an encouragement to seek out new sensory experiences. But it is also a reminder of the value of linguistic diversity.

Umpila, for example, is threatened by extinction. The number of native Umpila speakers is dwindling. And yet, when it comes to describing smells, this rare, endangered language apparently has the edge over booming, billion-strong English.

Source: BBC – Future – How your language reflects the senses you use