The clothes designed by Roy Halston Frowick – a member of the exclusive celebrity club, famous enough to be known by only one name – became a byword for luxury, status and fame, earning him close friendships among the decade’s triple-A listers like Liza Minnelli, Bianca Jagger and Elizabeth Taylor.

But it was the development of his debut, eponymous fragrance – the world’s biggest seller at the time – that made him realise the power of perfume.

That poignant moment of discovery is brought to life by Ewan McGregor in Netflix drama Halston when Vera Farmiga plays perfume artist Adele – the “nose” from International Flavors and Fragrances – who works with Halston, an enigmatic and hard-partying fashion icon who died in 1990, to create his new scent and encourages him to remember smells from his past.

His recollections of “spring grass and daffodils” spark flashbacks to childhood hugs with his adored mother and feelings of “innocence and comfort”. Later, smelling perfume with “notes of leather”, he recalls “soap or shaving cream” and images of the abusive father who beat her.

On screen the scents and the memories they provoke spark a breakdown in the designer, who helped dress the world’s dancefloors as disco took off and trendsetters in the world’s coolest clubs, like New York’s Studio 54, wore his clothes.

Tessa Williams, author of Cult Perfumes and the creator of her own fragrance range, knows well the power of perfume to provoke memory. She, too, is harnessing its potency to capture cherished moments missed in lockdown – the holidays, the parties and the music festivals – in a new range currently under development with London “nose” Sarah McCartney.

Williams, who writes from her home on a leafy country estate in Aberdeenshire, said: “There is a part of your brain that reacts to scent and makes this memory connection. There are scents that will bring about the memories in your life, whether those are good memories or especially traumatic memories. But most perfumes bring back beautiful memories.

“I can relate to Halston breaking down. Perfume is a powerful trigger. Always Chanel No.5 reminds me of going to my grandmother’s as a child, dressing up in my Sunday best. She was a talented artist, old-fashioned posh and lived in a big house in Ayr. All the girls in the family would be given a bottle of pure Eau de Parfum Chanel No.5 for Christmas. It was the magic of that scent. I will always remember that. I was a teenager when she died. It does evoke sadness but warm feelings too.”

Her first collection Elements features Fire, Earth, Air and Water. Her second, Triology includes Love, Faith and Hope – with the last of these launched at the start of the last lockdown when sales soared. She said: “Hope is the scent of grapefruit and bergamot. It is very uplifting.

“The new personal fragrances I am working on are the scents we have missed through lockdown. Seashore evokes holidays missed, the smell of sea breezes, sunshine, oil and coconut. Dandelion Musk is reminiscent of the music festival we lost in the pandemic; this one smells incredible with camomile and geranium, like a wild meadow. And, finally, Dancing With Strangers is the glamorous of scent of rose and iris that brings back those fabulous precious parties we have missed.”

She hopes her fragrances – like Halston’s – will, above all, make its wearer happy. “Scent can not only evoke a memory but change the way you feel too,” she said. “If people tell me they don’t feel good I always say go and spray yourself with perfume and you will feel different.”

Cult Perfumes by Tessa Williams is published by Merrell.

It is a special sense with a direct route to our brain

Sergio Della Sala, professor of human cognitive neuroscience at the University of Edinburgh

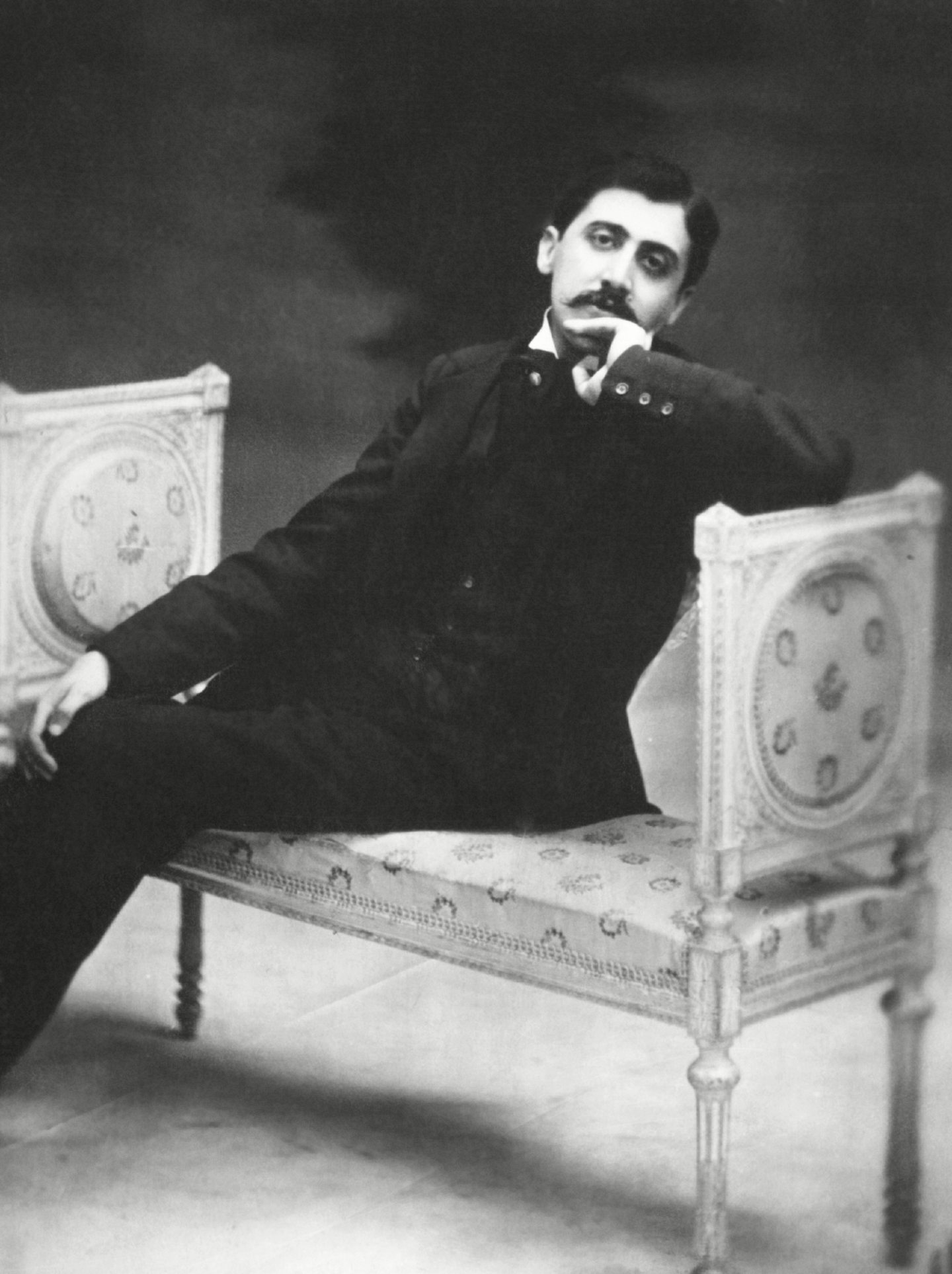

Many of us share a similar experience, made famous by the French author Marcel Proust who narrated that when dunking a petite madeleine in a cup of tea, his childhood memories spontaneously and vividly resurfaced.

A scent, a smell, a perfume, an odour can trigger our brain to access emotional memories, which would have remained buried otherwise.

Olfaction, or sense of smell, has a direct route to our brain, unlike other senses such as sight or touch. Molecules of air travel through our nostrils to reach the olfactory bulbs inside our nose, where they are converted into chemical signals that our brain interprets as odours.

From the olfactory bulbs, these odours go straight to a small, almond-shaped gland called the amygdala, which is responsible for decoding our emotions and to the hippocampus, a seahorse-shaped structure which processes our memories. Our sense of smell connects to these brain structures more strongly than any other sense. And does so automatically, so that our past memories are elicited without us putting effort into retrieving them.

This emotions/memories circuit within our brain becomes far more active when exposed to an olfactory stimulus than a visual or a tactile one. Hence, the smell of our aunt’s cookies is a far more potent trigger than seeing the same cookie or touching it. In short, smells are interweaving with memories and with emotions in our brain.

Haruki Murakami equated the sense of smell to a time machine, able to take us back and allowing us to relive emotions from our past. Therefore, losing our sense of smell, as happens with certain conditions such as Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s, and indeed Covid-19, can be catastrophic for our wellbeing.