You’ve probably never encountered real silence. Finding a place that remains sonically unmolested by the roar of commercial jets or the steady hum of highways is nearly impossible. Whether you live in a city, the suburbs, or on a ranch in Montana, sound in the modern world is more or less inescapable.

Turns out, that’s a good thing. Because when confronted with absolute or even near silence, human brains and ears react in some pretty weird ways—ways that can result in a wide range of bizarre sonic experiences. And their inner workings may even explain the auditory hallucinations associated with certain forms of psychosis.

The Search for Silence

“Sound is such a constant thing, we don’t even think about it” says Eric Heller, author of Why You Hear What You Hear. “Even a quiet house is 40 dBA (A-weighted decibels).” For context, zero dBA is considered the point at which humans can start to detect sound. A soft whisper at three feet is about 30 dBA. And a busy freeway at 50 feet is 80 dBA.

Now compare that with something like the -9 decibels of Orfield Lab’s anechoic chamber in Minneapolis, the quietest place on Earth according to Guinness, and you begin to see the stark sonic difference between the natural world we live in and the one contained within these artificial 3-D sound sponges.

Anechoic chambers are quiet by design, and are typically used to test things like audio equipment and aircraft fuselages. They’re able to squash reverberation (echoes) and keep external sounds out through a combination of architecture and special materials. Most are rooms within rooms, lined on all six sides with soundproof fiberglass wedges to kill sound reflections. (You’re usually standing on a suspended mesh wire platform while inside.)

Yet even after all that effort to block external sound and thwart internal reflections, silence is surprisingly hard to come by in an anechoic chamber. In fact, people have a habit of discovering new sounds both real and fake in these disorienting environments.

The Sounds of Silence

The real stuff is usually what people notice first. Starved for input, our ears and brain essentially go into overdrive. Sounds that are typically drowned out in the din of modern life become, in some cases, unbearably loud. Spontaneous firings of the auditory nerve can cause a high-pitched hiss, for example. Many people also have the strange experience of hearing their own blood pumping to their head, their breath, their heartbeat, as well as their digestive system’s symphony of gurgles and blurps. If you’re among the 5 to 15 percent of the population with constant tinnitus (ear ringing), you’ll definitely notice that, too.

And that’s where it ends for a lot of people. For others—like Radiolab co-host Jad Abumrad, who decided to sit in a completely dark anechoic chamber for an hour—things can get weirder.

In 2008, while sitting alone in a dark, sound proof room at Bell Labs in New Jersey, Abumrad heard a swarm of bees and the Fleetwood Mac song, “Everywhere.” The bees came first, about five minutes after Abumrad had sealed himself inside the chamber. During his hourlong stay, other faint sounds—like wind blowing through trees and an ambulance—seemed to appear and vanish from one or both of his ears. After about 45 minutes, Abumrad began to hear distant lyrics to a song, a song that sounded as if it was coming from a neighbor’s house: Ohhhhh Iiiii, I wanna be with you everywhere.

“The room is quiet, my head apparently is not,” he said in a followup post on Radiolab’s website.

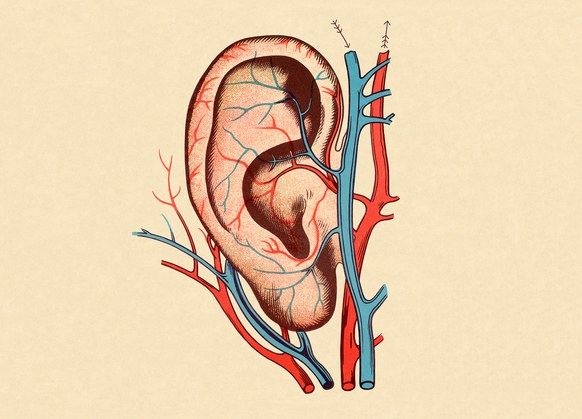

“For a long time it was assumed that sound simply enters the ear and goes up to the brain,” says Trevor Cox, a professor of Acoustic Engineering at the University of Salford. “Well, there’s actually more connections coming down from the brain to the ear than there are going back up it.”

Why is that important? Well, for one thing it allows the brain to tweak the gain levels in the inner ear, Cox says. But as Polish neurophysiologist Jerzy Konorski pointed out in the late ’60s, those brain-to-ear connections are also the likely cause of auditory hallucinations. His theory, borne out by recent brain imaging studies, was simple: We’d all be constantly hallucinating were it not for the grounding input we receive from our other senses.

These inputs essentially help our brains distinguish between thoughts and reality. Take away or greatly diminish one or more of those sense organs, Konorski reasoned, and this would “produce hallucinations physiologically and subjectively indistinguishable from perceptions.”

In other words, while sitting alone with your own thoughts in a pitch black, soundless room, whatever happens to pop into your brain, whether it’s an earwormy Fleetwood Mac song, the voice of a friend, or a random sound triggered by some memory, you’re more likely to perceive it as real.

Indeed, most people who have auditory hallucinations have some form of severe hearing impairment, be it physical or neurological. But as Oliver Sacks recounts in his book Musicophilia, sometimes all it takes to trigger your own hallucinatory symphony is the prolonged silence of the calm open sea or the auditory monotony of a deep woods retreat.

Source: Big Question: Why Can Silence Make You Hear Things That Aren’t There?