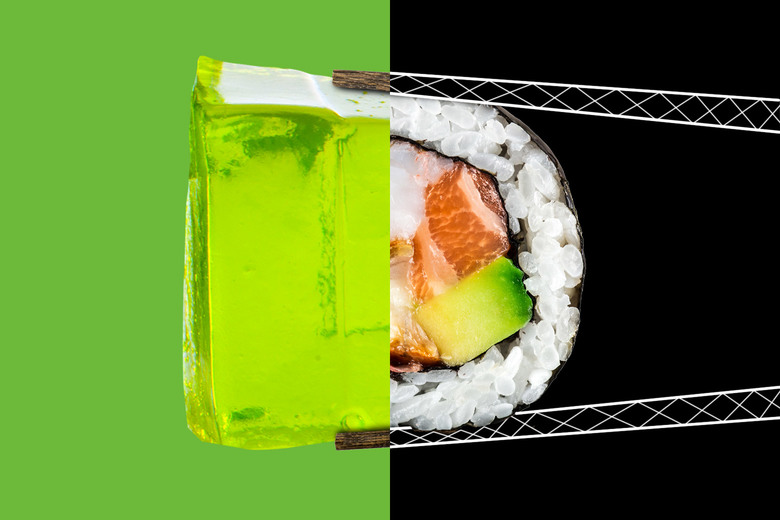

Or at least, that’s the idea. This technology is just one set of a myriad of gizmos and gadgets that a company called Project Nourished has been developing to provide its customers with what it bills as “gastronomical virtual reality experiences.”

Like other experiments in digitally or otherwise simulating or enhancing taste, Project Nourished’s innovations are mainly based on some somewhat counterintuitive scientific principles that show that much of what we think we taste, we don’t actually taste. Instead, our full experience of taste is deeply linked to our other senses: smell, vision, touch, and even hearing. Influence those other senses—with, say, familiar aromas, shapes and colors, textures, or a noise like a satisfying crunch—and you can trick how you perceive taste. “Think about birthday cake, and how we crave that experience,” said Jinsoo An, the founder of Project Nourished. “It’s an experience that’s edible, with the cake and everything that goes into it, but there’s also the singing, the candles, the decoration, all of which are layered on top this very rudimentary food. It’s really also about the experience.”

Project Nourish’s experiences aren’t yet available for trial. An said that the company plans to open-source all the technology in the near future so that anyone can use its model to create their own dining experience. But when they do debut, they won’t be alone.

Other forms of augmented reality and virtual reality tech has started to trickle into restaurants in the form of “experiences” that range from mostly gimmick to totally uncanny. For example, at a new Tokyo virtual reality restaurant, visitors are guided through a multicourse meal meant to illustrate chapters in “the journey of life”—complete with a live narrator, light show, soundtrack, gusts of wind, and, for one course, VR headsets that bring fashionably dressed farm animals to the table to dine alongside you. (A reporter that dined there described it “magical.”) On the other end of the spectrum, last spring in London, restaurateur Jamie Atherton launched an augmented reality cocktail bar. It, less magically, requires imbibers to download an app that allows them to see works of art and other visuals associated with their drinks.

This latter idea was picked up by Italian futurists F.T. Marinetti and Fillia in their 1930 Manifesto of Futurist Cooking. Among other absurd and unpopular suggestions like banning pasta—a meal they tied to sluggishness, pessimism, nostalgia, and lack of purpose—they advanced the idea that some food should only be experienced with the eyes and nose. As part of this, the pair proposed dining experiences that involved the rapid presentation of a series of dishes, some to be eaten and some to simply smell or appeal to the eye and imagination. They also proposed that traditional kitchen equipment, including knives and forks, be banished, and instead replaced by the equipment of modernity, like ozonizers, ultraviolet lamps, dialyzers, and chemical analyzers. By presenting the population with these imaginative food combinations, they wrote, they aimed to advance the “noble and universally expedient aim of changing radically the eating habits of our race, strengthening it, dynamizing it, and spiritualizing it” by ridding the population of the inefficient food of “quantity, banality, repetition, and expense.” (You may not be surprised to learn that Marinetti was also developing his ties to Mussolini at the time.) Fortunately for all, traditional Italian food survived.

There’s reason to think we may be getting closer. Scientists at Cornell University published a study last July that supported hypotheses virtual reality can be used to enhance taste. In it, participants were given identical samples of blue cheese in the two virtual environments: one a barn full of cows, the other a botanical garden. Those who were in the barn setting rated the blue cheese as more pungent, likely due to the audiovisual cues spilling over into other senses, said Robin Dando, the food scientist at Cornell who spearheaded the study. Dando said he saw the study as a “proof of concept,” confirming existing research with the aid of new technology.

Charles Spence, an experimental psychologist at Oxford who heads its Crossmodal Research Laboratory, suggested that we might think of much of what’s on the horizon for our taste buds as a pursuit of “digital seasoning.” Beyond VR and AR, this might include the possibility of electrically stimulating our taste buds—a technique that’s existed since the 1950s or 1960s that basically involves using a silver electrode at the tip of your tongue to send signals that stimulate the areas that receive salty, sweet, sour, bitter, and umami tastes. It only works in some people. And, thus far, it’s been easier to produce salty and sour than it has been to produce sweet. But the technology has already been incorporated into commercial prototypes, like an electro-fork that will zap your tongue into thinking you’re tasting salt.

But, Spence says, this method brings us back to the main issue with taste. “The problem arises that most of what we think we taste, we actually smell, so even the perfect electric taste wouldn’t give [smell] to us,” Spence said.

This brings us to the real biggest roadblock to remaking our tastes through technology: smell. Smell remains a kind of unhackable sense—strangely primitive, deeply complex, and hard to mimic even with our most cutting-edge tech.

The electrical current route, for one, hasn’t been very promising. In a study published in 2016, researchers attempted to activate smell by applying electrical currents in the nose to activate subjects’ olfactory receptor neurons. Of the 50 people that participated, not a single one perceived an odor. This likely has to do in part with how smells combine. “It’s more of pointillist sense,” Spence (who was not involved in this study) said. “A nice wine might trigger hundreds of sense receptors and we don’t really know those receptors combine.”

A more promising option may lie in aromatics—the approach Project Nourished is taking to the tricky business of smell. Rather than trying to fake it, the company is using chemically engineered scents diffused during the meal.

These limitations were part of what led to the downfall of DigiScents, a company that during the height of the dot-com bubble raised $20 million to create what one of the founders called “a printing press for scents”—a way to digitally transmit every existing smell. A lack of consumer interest, combined with the absurd cost of digitizing scents, led it to shutter in 2001, just two years after the prototype was launched.

Katsunori Okajima, a professor and researcher at Yokohama National University in Japan who focuses on virtual reality and sensory and brain sciences, said that tricking the brain is within the grasp of our scientific capabilities. He has developed and tested an augmented reality platform that performs simple visual tricks—adding cream to coffee visually, or making salmon look like tuna. The visuals were fairly successful at fooling people’s brains, perhaps in part because of their simplicity. Salmon into tuna isn’t water into wine. Okajima hopes to make a tablet version of his AR conjurings available for commercial use later this year.

“It’s like an illusion,” Okajima said. “Illusion is not mystery, but a science.”

Future Tense is a partnership of Slate, New America, and Arizona State University that examines emerging technologies, public policy, and society.

Source: What 3D-Printed Virtual Reality Sushi Might Foretell for the High-Tech Future of Eating