Ammonia hits the nose with a caustic punch, a fitting warning from a gas that irritates the throat and sends the lungs gasping for air. But to Jan Schnorr, CEO of C2Sense, it smells like sweet opportunity.

Schnorr’s Cambridge startup makes a device that can sniff out ammonia and, potentially, nearly every other gas, even in tiny concentrations. One market targeted by the company is commercial customers including chicken farms, where ammonia from the birds’ waste can harm both animals and people, and workers’ noses are sometimes so damaged by the substance that they can no longer tell when the gas has reached dangerous levels.

C2Sense is one of a number of companies seeking to improve technology for detecting and identifying multiple scents, a field where sensors have traditionally been slow, unreliable, or prohibitively expensive.

Experts say the difficulty comes in part from the sheer complexity of our sense of smell, which is perhaps the least understood of the human senses.

When we inhale through our noses, we are using hundreds of receptors, each of which is sensitive to thousands of different compounds that help our brains understand what’s in the air nearby.

But scientists have struggled to understand smell as well as they comprehend how our eyes absorb light or how our eardrums pick up vibrations.

Mainland says science is advancing to the point where researchers will soon be able to break scents down into primary components, much like the primary colors that make up the spectrum we see.

Such a scheme will require advances in our understanding of why certain compounds smell the way they do, and increasingly sophisticated sensors.

Aromyx Corp., a Silicon Valley startup, sells a sensor that it says replicates human smell and taste receptors and works with a software program to explain how a human might experience a given compound.

Aromyx said its technology could create digital definitions of scent that can be used in the fragrance industry, for instance, to tweak and edit aromas with a precision that is not available today.

‘We rely on [scent] so frequently in everyday life, but we have no way to quantify what we’re smelling.’

Aryballe, a French company, meanwhile, makes a mobile sensor that it says can pick out hundreds of scents.

Back in Cambridge, C2Sense does not claim to be able to mimic the human nose with the same precision; its sensors now are designed to pick up only a maximum of 16 gases at a time — though Schnorr said that could be expanded.

But the company said it will create affordable devices that could add olfactory capabilities into the web of connected devices that are becoming increasingly common in smart homes and workplaces.

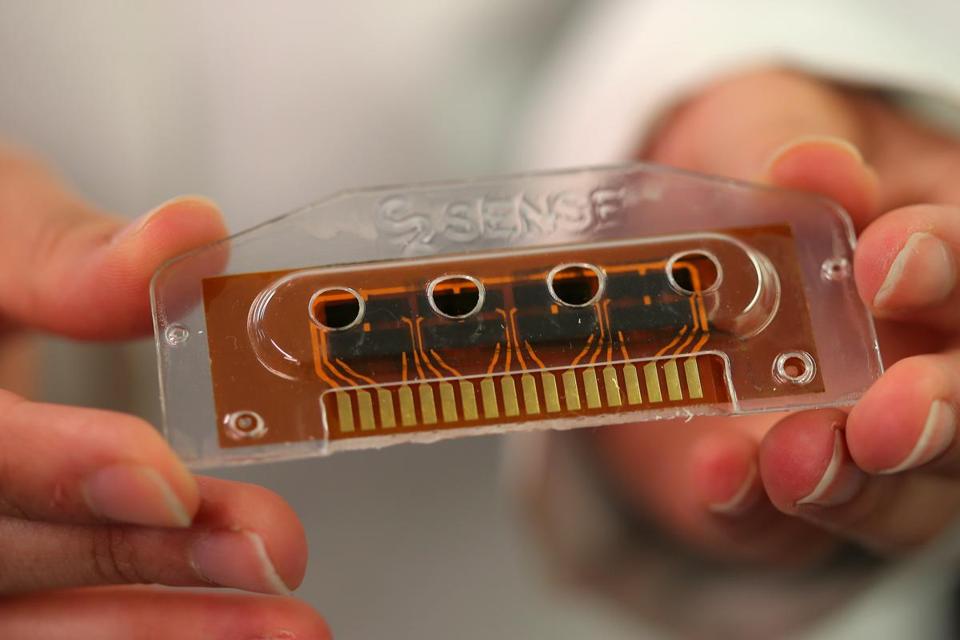

The company’s monitors look like wireless routers, and they contain replaceable cartridges that hold tiny carbon nanotubes formulated to react to specific gases.

C2Sense is running a pilot program for the poultry industry in which it charges between $500 and $1,000 per year for a device, which includes the cost of cartridges along with access to detailed data on the machines’ readings. The company also is developing badge-sized sensors that workers can carry.

Merry Smith, senior scientist at C2Sense, envisions a range of applications, from pollution detection to in-home use.

“I’d love to have a smart home that would tell me when my eggs were burning a little bit because I wasn’t paying attention to them, or my refrigerator to text me at work and say, ‘You should really use those avocados tonight,’ ” Smith said.

Hong Li, a University of Delaware food and animal scientist, said most chicken farmers can’t afford equipment that would allow them to effectively monitor for ammonia now.

He said technology advancements are already having an effect. He used C2Sense sensors in a study he conducted of two similar chicken houses. In the one where the sensors alerted managers to problems right away, he said, chickens were heavier and offered better meat. The new technology, Li said, “really can improve the animal productivity and animal welfare.”

C2Sense has also been working on other applications for its product: a system to alert grocery warehouses when produce is in danger of spoiling, for instance. Schnorr also imagines that he could make a device to sniff out drugs, as dogs do now.

There’s also the possibility that sensing technology could work like a camera or recorder for scent, allowing a user to examine the components of an appealing odor so it could be re-created later.

“We’re at a point right now where adding a third dimension to communications is conceivable,” said David A. Edwards, a Harvard engineering professor who has been working on the science of taste and smell through projects including Cafe ArtScience in Cambridge.

Edwards is working on the Cyrano, a “digital scent player” that blends and sequences aromas in an effort to promote wellness and productivity. His company, oNotes, is using the devices to study topics including how changes in health can affect people’s sensitivity to smell.

Venture investors have put about $5.3 million into C2Sense, optimistic that it will be on the forefront of the use of software to quantify the factors associated with air quality and scent, creating what backer Reed Sturtevant described as “a whole new way to understand what’s happening in the physical environment.”

Sturtevant, general partner at The Engine, an MIT-linked venture firm that is an investor in C2Sense, said the technology has the potential to shepherd in technological changes as vast as those brought by the advent of digital photography.

The aromatic equivalents of Instagram, self-driving cars, and facial recognition are hard to imagine today, but in retrospect, Sturtevant said, they may seem obvious as “sensor technology becomes better, and cheaper, and easier to integrate into networks and software.”

Andy Rosen can be reached at andrew.rosen@globe.com.

Source: What’s that smell? Electronic noses can sniff it out – The Boston Globe