ANGELINE Cheng remembered the first time she thought she was probably a little bit different. As a 15-year-old chatting with her friend from choir in secondary school then, she casually asked her friend about her “C-chord colour”. “My friend gave me this really weird look,” recalls Ms Cheng, the 22-year-old who is now in her final year of university studies. When the C-major chord is played on the piano, Ms Cheng sees yellow. The D-major chord is a darker brown; F-sharp major is orange; E-major a deep emerald green; and A-major is “just really red”.

The young Singaporean is one of an estimated four per cent in the world with synaesthesia, a crossing of wires in the brain that causes one major sense to connect to another. So when Ms Cheng hears music, she also sees a coloured representation of it.

The reaction from Ms Cheng’s friend led her to read up about the topic on the Internet, where she realised she had a form of synaesthesia.

The range of synaesthesia adds to its rarity and complexity, with about 60 forms of synaesthesia found in a study of about 930 synaesthetes. Over 60 per cent of them see colours in their letters or words. Others reach orgasms in colour, see music in complex patterns, or feel a literal heartache out of hyper-empathy for a friend in pain.

This isn’t a result of an overactive imagination. Brain-imaging technology and renewed interest from researchers have validated synaesthesia – an experience invisible to all but synaesthetes. The study of cognitive neuroscience, in particular, had much to contribute to the discovery of the condition when it took off in the 1990s with the use of magnetic resonance imaging or MRI.

Such functional MRI scans measure oxygenated blood flow. When a region of the brain is active, it requires more oxygen, and blood that is rich with oxygen rushes to the area. For example, for those with synaesthesia that is associated with colour and words, the V4/V8 areas in their brain – the sections in the brain’s left hemisphere that processes colour perception – are stimulated when they hear or read text.

The scanner, which has a strong electro-magnet built in, picks up the change in magnetisation between oxygen-rich and oxygen-poor blood. The change is also tied exactly to the timing of the activity, making the condition definitive, according to research from Julia Simner, the lead researcher on synaesthesia at the University of Edinburgh.

Research shows that sensory associations behind synaesthesia tend to be arbitrary, and not triggered by childhood memories, though most synaesthetes recall their odd experiences as kids. And if two synaesthetes have the same form of synaesthesia, they would not make the same sensory ties.

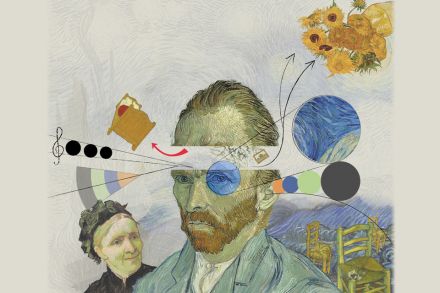

Synaesthesia, which tends to run in the family, is not seen as a disability. And with their heightened sensitivity to colour and music, synaesthetes are naturally drawn to aesthetics – synaesthesia is estimated to be seven times more common in artists and writers than everyone else. Stevie Wonder and Pharrell Williams have it; so did Vincent van Gogh.

But it is hardly explored in Singapore, likely because synaesthetes such as Ms Cheng don’t need to seek a “diagnosis” for the condition. The School of the Arts and Lasalle College of the Arts say they do not know of any students with synaesthesia at the moment.

French vanilla

This reporter first learnt of synaesthesia in 2014 when based in New York, and where synaesthetes shared their experiences.

Then, she met musician and synaesthete Evan Shinners, who doesn’t just see colour, but feels it when he plays music. For him, every hue hits that small space just at the bottom of his ribs. Yellow’s jumpy jolt is different from red’s angry knot. The F major is yellow to the Juilliard graduate, while F sharp major is red. He reached his epiphany at 19, at a New York Philharmonic Orchestra concert. At that moment, he recounted feeling awash in a cream yellow, like French Vanilla ice cream – and the intense experience finally pushed him to research what he thought most people experienced.

Other synaesthetes who react to music may associate colour with musical compositions, musical instruments, or the tone of a note, which can change according to the instrument that the note is played on. Mr Shinners cannot feel colours in Japanese music, because of the difference in tone. Japanese music has a pentatonic scale, or a five-tone scale. Western music has a scale of seven.

In a similar way, Singapore’s Ms Cheng sees colour in music when it is played on the piano, but not when a piece is sung by a choir.

Mr Shinners turned obsessive with colour, as his bookshelf showed. Each title – be it on Lao Tzu, or Edward Hopper – stood erect next to another not by theme, but by its colour’s gradient. He suspects he has been picking books that are colour-matched all his life, though there is a small pile of books that have been ostracised for the colour of their skin.

In New York, there was also writer Maureen Seaberg, who experiences several forms of synaesthesia, and has a “fourth cone” for colour perception. She sees a plethora of colours – all 100 million of them. Most see one million. “I’ve always thought that I should name the lipsticks for cosmetic companies. I’d say, ‘that’s not amber, that’s spiced pumpkin. You’ll just have to trust me on this one’.”

Armed with a newfound understanding of her unique neurological condition, Singapore’s Ms Cheng channelled this ability into an art installation for her A-level exam (for which she got a B grade). Visitors would walk through a small room with Charles Gounod’s version of Ave Maria, and watch as colours that represent the musical notes dance on white plastic boards. She had told her junior-college art teacher about her condition, and was told to just explore it further.

Over in the United Kingdom, James Wannerton was 21 when he saw a woman on television talking about synaesthesia, and suspected that he hadn’t been the only one who had crossed senses. He went to the doctors, and despite the odd looks, underwent a series of MRI scans. When doctors played music and words, the part of Mr Wannerton’s brain linked to taste “lit up”.

Sex and hardboiled egg

Mr Wannerton, head of the UK Synaesthesia Association, attaches words to tastes. While synaesthesia has been difficult to explain because of its subjectivity, the sensory associations do not change over time, says Mr Wannerton, whose own name tastes like a piece of gum chewed till all its flavour is gone, he tells The Business Times via email. (The name Jamie tastes like gum too, just softer.)

At 16, his then-girlfriend recorded tastes that words evoked for Mr Wannerton. Time tasted of shepherd’s pie, and sex felt like the yolk in a hardboiled egg. Years later, Mr Wannerton passed the same notebook on to the University of Edinburgh, where researchers hold an extensive list of his taste associations collected over 15 years.

“The researchers then compared the two lists and the associations were 100 per cent consistent. That’s written evidence of consistency covering a 35-year time span.”

Mr Wannerton’s close friends since early childhood have tantalising names. “When it came to girlfriends, my synaesthesia again played a large part in proceedings because the taste and texture of their name was just as important and attractive to me as their pert nose or sparkling personality,” he adds. It becomes a bit more problematic at work, where colleagues with “horrible tasting names” are clearly not horrible by choice. He shortens their names, or adds the middle name to change the overall taste combination.

He has trooped to all 270 stations that make up the London Tube, and published his interpretation of the iconic system that turns the city’s shopping stretch, Bond Street, to hair spray, and Covent Garden to one with chocolate digestive biscuits.

Not all stations are palatable. West Silvertown, an industrial estate in Greater London, gives him a stomach-churning concoction of blood and chocolate. There are textures, and temperatures, to his sensory experience: Aldgate is a piece of bacon just whisked out from the fridge, while Plaistow smears like wet chalk.

Ms Cheng’s synaesthesia is not disruptive to her life, and her family and friends have largely been curious about the unique condition. She faces no discrimination. “My parents didn’t think I had mental issues,” adds Ms Cheng.

But older synaesthetes have had to carry their sensory overload in secret, amid misconceptions that synaesthesia is a result of hallucinations.

Among the many cross-sensory experiences she has, Carol Steen, an art teacher at New York City’s Touro College, has the ability to see scent in colours. Yet, it took a long time for Ms Steen, who is now in her 70s, to even talk about it. For 50 years, Ms Steen kept her ability hidden from most people. No books talked about synaesthesia, and no one discussed it. And so, she retreated into silence, even as synaesthesia became her muse for her paintings and sculptures. But Aug 31, 1993 – a date Ms Steen rattled off like it had been seared in her mind – was a day of awakening. Ms Steen was working in a warehouse, sculpting plastic toys that are given out to kids at fast-food restaurants. To get through the monotony of the task, she had her Walkman on.

Without warning, her headphones were lifted. Her colleague, who had heard her describe colours for letters, numbers and pain, nudged her to listen to the radio. She put down her tools, and heard a neurologist explain a cross-wiring condition known as synaesthesia – that it was rare, but real.

Ms Steen spoke to the neurologist and out tumbled her secrets. That the letter “A” is still the prettiest pink. That she used to quarrel with her father about the right shade of yellow for the number five, though he refused to describe his synaesthesia in detail. That she paints the coloured visions she sees from getting a shot, or listening to Coldplay. That the colours float, brighten, and disappear in seconds.

Kindred spirits

The same year, at an art exhibition in New Jersey, she opened up about her synaesthesia and “came out”. She founded American Synesthesia Association two years later, so that other synaesthetes could find, and form, a community.

There’s palpable relief from talking about synaesthesia, says Ms Seaberg, who came to terms with her synaesthesia at the age of 27 after finding a book on the condition by chance.

“The irony is, I was a child of the 1960s, when there was obsession with psychoactive drugs. But unlike the hippies, we never lose grip on reality.”

Like most synaesthetes, Ms Seaberg hates crowds, because she often hears, sees, and feels too much. She had to give up crime reporting, because the work literally hurt from her mirror-touch synaesthesia, an extreme form of empathy. She would physically feel sensations – sometimes, pain – on parts of her body, mirroring where victims had been wounded.

She moved into writing books, but struggled to edit her first book. “When I edited paragraphs, I would change words because there were too many green words in a sentence,” says Ms Seaberg. “It’s ridiculous. Eventually, I just had to stop. If the word conveys the meaning, I had to let it go.”

Singapore’s Ms Cheng is aware that it has been easier for her to explain her condition because the term “synaesthesia” has been coined and explained online. Given the wide spectrum of synaesthesia, she hopes the topic can be discussed further in Singapore.

It’s fortuitous that musicians from Tori Amos and Mary J Blige to Lady Gaga and Billy Joel have been discussing their synaesthesia in public. Billy Joel uses the colours he sees as mnemonics to compose music. Biographical accounts now show that early composers including Leonard Bernstein, Duke Ellington, and Franz Liszt, also had synaesthesia.

Mr Wannerton says the biggest misconception used to be that people with synaesthesia were making the whole thing up. In these modern times, the problem seems to be teaching people how to pronounce the word correctly.

In a way, he can’t help but be optimistic – his future tastes of peaches.

Amendment note: The story has been amended to change a typo in the surname of Angeline Cheng.