Every night, before going to bed and leaving her in the care of my husband (she is too old for the stairs and he is a night owl), I kiss her in patterns. Three on the head, three on the nape, three on the belly. Then I inhale its scent, deep, from the warm place on his torso.

Repeat, repeat, repeat until you are satisfied, or until you feel my husband’s gaze, and excuse me quickly and quietly. He has reason to look: the longer I stay, the more likely it is that our sleeping dog will wake up and need to be brought out into the yard. He says this out loud and gently encourages me to leave.

But the other reason is unspoken. I learned through therapy the necessary tools to manage my obsessions, my compulsions. I have seen others strategically defeat their OCD and enthusiastically encouraged them. However, now, I’m not even trying to stop my rituals.

I don’t want to try, right now, where each kiss and each deep breath could be my last sensation of my dog’s fur against my lips and the last smell of the rich scent that belongs only to her.

I take photo after photo to preserve it.

When it finally passes, I ask the vet to keep a lock of her soft fur, along with the clay tracks from her tracks, to take the rest of her with me to the best of my ability.

But you cannot preserve the aromas of our pain.

How fast do they leave us

He was finally succumbing to a brain tumor that had spread to his lungs. His departure would be terrifying, said the vet, and could land on Christmas Day in front of my children. The kindest act would be to let her go in peace.

So I do. She dies in my arms, the taste of her latest burger still in her mouth and the feel of my lips against the top of her head. It happens quickly, so fast that my rituals are punctuated, kiss, kiss, kiss and settle only on his head. I don’t have time to do all the steps.

Then she leaves, peaceful. Still warm when I tell the vet that I need to go. I don’t want it to get cold; the vet agrees to stay with her while I go out.

HIS SCENT IS GONE … I KNEW WE CAN’T BOTTLE THE SCENTS OF OUR LOVED ONES, BUT I DIDN’T KNOW HOW FAST THEY LEAVE US.

A final set of rituals and I will go. I kiss her on the head three times. The touch of his neck. Your belly

I lean in to inhale, in the still warm place beside him.

Respite. I try again and again and again.

“He’s gone,” I tell him, panic increases, as the vet bows his head in sympathy or concern.

“What?” She is kind, gentle.

“Nothing.” I try again and give up. I kiss her on the head, over and over, over and over, before finally getting up and reaching the door.

Her body is still warm, but her scent is gone. Less than two minutes have passed. This is something that no one has warned me about; I knew we can’t bottle the scents of our loved ones, but I didn’t know how fast they leave us.

At home, however, I have a secret.

A place where memories live, where I can inhale the stories of those who have gone before me. I won’t find my dog there, but I will find generations of women huddled in the sweet smells of our family’s bedding.

At night, I close the closet door with my foot, not knowing who left it open. My children, perhaps, who still do not understand that the aromas of our past cannot be contained in jars or captured on film.

I open it again and rub my fingers on the smoothest sheet; discolored, worn, as smooth as the back of my son’s leg, or my grandmother’s cheek when worn and worn, but alive.

When she died, I was still a child and these sheets lived in my mother’s hall closet. I pulled them out and wrapped them around my shoulders, buried my nose in them, inhaled the memories of my grandmother’s hug, her voice, her touch, all captured in a scent. These moments, where my rituals began, calmed me. It would be three more decades until a diagnosis was made, until I rejected the help I embraced for others and allowed my rituals to grow.

My mother still has most of the bedding, but when I moved west she sent me enough sheets for the smell to fill my own closet; 1,400 kilometers away, I also feel my mother’s touch when I open this door.

I call my mother and ask her to describe it, this smell that we have never noticed in words. “I can feel it,” she replies. “It’s old. My mother’s bag, my grandmother’s scarves. When she was little, she folded them. Babies in a hammock called them. Have I told you that story?” I shake my head, no, although she can’t see me.

Beautiful and tragic

I don’t remember my mother’s grandmother. He was not there to fold the scarf. I’m not sure if I’ve met her. I don’t ask, because asking builds a wall between us: how do we have such different memories, my mother and I, when my life is so intertwined with hers?

She had a sister, once, whom I never knew, who died when she was a child.

Does my mother smell her sister’s scent on these sheets?

I AM MY GRANDMOTHER’S WRITER, I AM MY GRANDMOTHER’S EXPLORER.

There are stories buried in our bedding. My grandmother’s stories. From my great-grandmother. My aunts, perhaps, both living and dead. The stories of girls and women, told through detergents, bags, beds of generations that I never knew. Strength stories. Beauty. Deprivation. Maternity. Me too, you too, us too.

“They also smell like grandma,” I offer, acknowledging what divides us.

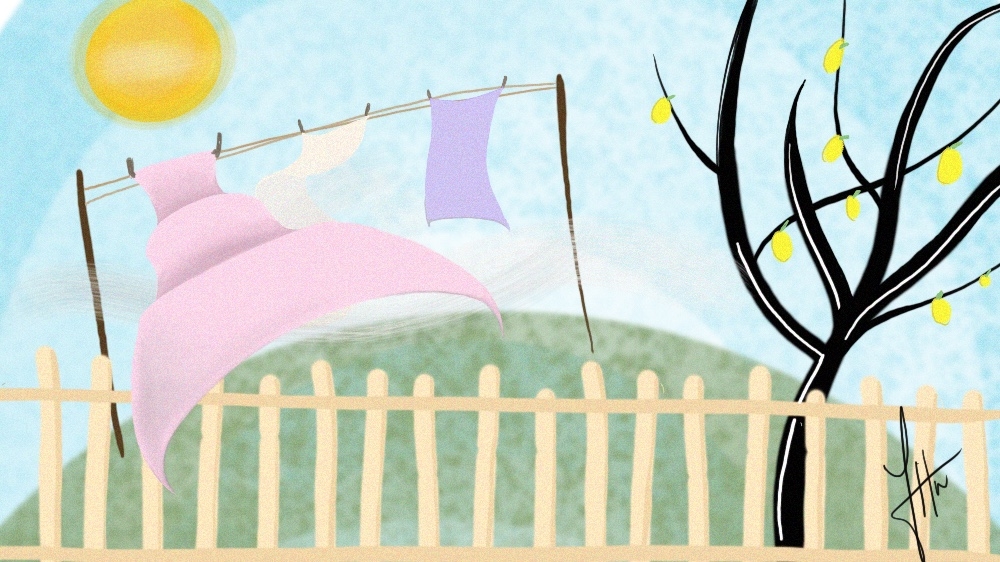

My father’s mother. He dried the sheets on the line in his backyard; once smelled of lemon and sun, but now they have been mixed and rewritten in both cabinets. Where my grandmother was soft, with books and bird carvings and songs, my grandmother was desert and lakes and outside, a farm girl from the Midwest who once rode a pony to go to school with her sisters. Granny’s sheets were white, cream, yellow, silky. Grandma had swirls of shocking pink and was rough to the touch.

“You think? I never noticed,” my mother replies.

She wouldn’t notice, of course she wouldn’t notice, because my grandmother was not hers.

We smell exactly the same scent, my mother and I, when we opened my closet door. And when we open her closet door, after passing through endless fields of wheat and corn to bend my children in my childhood home, in my family.

However, the smell is different. His, full of memories that I have never had and faces that I have never seen. Mine, filled with everyone who created me, including my mother. I smell doll and book houses, gardens and sunshine. I am my grandmother’s writer, I am my grandmother’s explorer.

At the same time, this is beautiful and tragic.

My own children will never meet my grandmothers.

Right now, they are small; Our lives are tangled.

When you open this closet, someday, you will smell your mother, your grandmother, and something I have not yet imagined.

They will make their own memories, as it should be.

Generations of missing women

But also, they will forget it. Those I have loved will forget, through scents they have never known.

I show photos to my children. Easy memories; carefully they will last forever. I can tell you illustrated stories: Here’s your great-grandmother on her farm! Did I tell you they had to get up and do chores every morning? So go to school, all six, on the back of that pony? That for Christmas they were lucky to get an orange, a little chocolate, a little toy? How lucky are you to get the books, the games, the new Pokémon figures!

But I can’t tell you, can I, that someday you will try to find a memory and it will be gone?

Someday, you could bury your nose in your dog’s coat and panic when you can no longer smell it. It is possible that the pain will invade you in the next days, but also with the feeling of anxiety of something unrecoverable, lost. A memory, disappeared.

A memory that I can see in a photo, but I cannot hear it. I can’t touch it. I can’t feel it. I can only try, with my head buried here in my closet, to smell it. Rituals of obsession, compulsion, necessity.

I check the closet door every night before bed to make sure it is closed.

Neither my husband nor my children are allowed to wear these sheets, as if the scent seeps down the hall or onto their bodies and floats away; Generations of women left, with no way to keep them in place.