Perfumer Dana El Masri on the place of the nose in a masked-up world

I stopped wearing perfume on March 14, 2020. In the grand scheme of things that were happening at the time—the sudden mandate to work from home “just for two weeks,” the panicky visit to the grocery store to find shelves bare, the spiralling hysteria on social media—it was a minor, barely conscious decision. All I knew is that I loved that perfume—Glossier You, bought on a trip to New York a few months earlier, forever associated with the woman one table over at Jack’s Wife Freda interrupting me mid-chicken sandwich to say how good I smelled—and I didn’t want to ruin it. It was an impulse to not associate it with this weird, chaotic time. I never thought that a year later, spritzing it on the inside of my wrists still wouldn’t be a part of my morning routine.

It turned out to be a weird bit of prescience about one of the strangest ways this pandemic would affect us: our relationship to smell, and the scents of the world around us. We wear masks, which dull what we can smell. We’ve lost the casual joy of standing in an elevator with a stranger wearing a great perfume. The smell of hand sanitizer is both comfort blanket and trigger. And, of course, COVID-19 is a disease that often first manifests in anosmia—the technical term for loss of smell that sometimes never returns.

“We really underestimate our sense of smell. It’s integral to social interaction, to our happiness, to how we move through the world”

For perfumer Dana El Masri, anosmia is an omnipresent fear. “When I even get a cold, the world is grey-scale,” says the Montreal-based founder of Jazmin Saraï, who relies on her hypersensitive nose to create hand-crafted fragrances. “We really underestimate our sense of smell,” she says. “It’s integral to social interaction, to our happiness, to how we move through the world.” In a world where death is carried on aerosolized droplets, our relationship to smell—and by connection, our breath—has changed radically. “There’s this intrinsic mistrust of the air we breathe,” she says.

As someone with synaesthesia—the phenomenon of perceiving one sense simultaneously with another, so sounds may be experienced as colours, say—El Masri is attuned to how important smell can be in our daily life. “I can smell bullshit,” she says laughing, before adding that “smelling other people’s feelings” is something we all do unconsciously. “We sweat differently when we’re nervous or excited,” she explains. “Most people don’t realize it, but we’re all releasing different cues, and we’re smelling each other.” Without knowing it, we’re all absorbing each other’s stress on an olfactory level—which in turn heightens our own fear response.

Assuming you’re around other people. Most of our interactions these days are virtual, meaning we’re missing out on olfactory cues that we’ve been subconsciously leaning on all our lives. It’s yet another reason why Zoom meetings feel deeply unsatisfying—and why they’re so exhausting, as your other senses try to make up for that information deficit. “We smell with our brain,” says El Masri, noting that the brain processes smell, memory and emotion in the same area, known as the amygdala. “The nose is a tool, and there’s a reason it’s in the middle of our face.”

“The nose is a tool, and there’s a reason it’s in the middle of our face”

Making that link between scent and feeling is El Masri’s life’s work, although it took her till her early 20s for her to realize it. Born in Budapest and raised in Dubai before immigrating to Canada at 18, El Masri has a Lebanese Egyptian background. “Scent is in our language, it’s in our ritual, it’s so embedded,” she says. She used incense and other scents to make herself feel good long before she knew you could make a career out of creating fragrances that would do the same for other people. Educated at the prestigious Grasse Institute of Perfumery in France, she lived in New York for a time after starting her own line seven years ago.

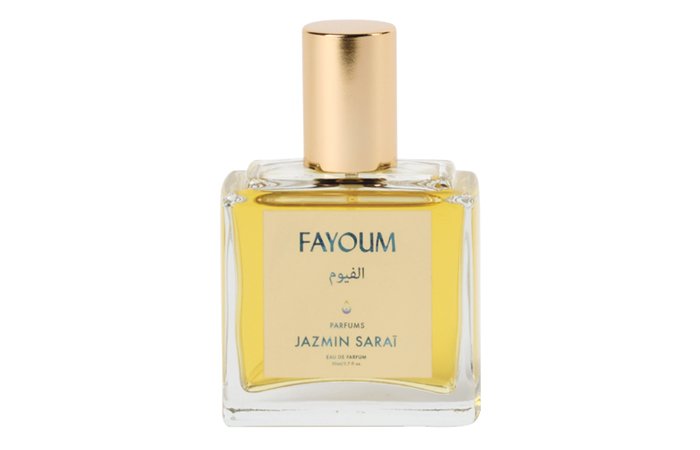

When COVID hit, she had just brought a new scent, the violet-and-mimosa-forward Fayoum, to market. “That was…interesting,” she recalls with a wry laugh. She remembers that apocalyptic feeling at the start, when it seemed the world was in survival mode. “I thought, ‘Perfume is luxury. Do people really need it?’” The answer, it turns out, was yes. “I noticed people would buy perfume as this small pleasure to bring them joy during this time.”

Rather than avoiding forming any scent memory at all (as was my instinct), El Masri advocates leaning into scent, forming positive associations in a negative time. It’s something she’s practising daily, wearing jasmine oil in the morning for its mood-boosting effects, or burning clary sage incense at night to wind down.

“At 16 weeks [in utero], you can smell what your mother is eating, because scent is the only thing that passes through the amniotic fluid”

The reflex to reach for certain scents in times of stress is a primal one. “Your sense of smell predates your birth,” says Dawn Goldworm, a professional nose and founder of 12.29, a New-York-based olfactive branding company, which translates brands like Valentino and Cadillac into signature smells. “At 16 weeks [in utero], you can smell what your mother is eating, because scent is the only thing that passes through the amniotic fluid.” Smell, in essence, is the first way we understand the world. “When you smell something as a child, you have a feeling about it, and you deposit that in your memories.” Goldworm explains. “There’s a reason a lot of people find lavender calming, and that’s because a lot of baby products in different parts of the world use lavender.” Some research even suggests that the reason so many people like the smell of vanilla is because it’s similar to that of breast milk. Fragrance, it seems, is deeply Freudian.

While we can form new olfactive preferences in adulthood—generally around highly charged emotional events, like the first time we fall in love—as adults we tend to “recycle experiences,” as Goldworm phrases it. “Unless you have a traumatic event that’s linked to smell, and you can uproot all these olfactive preferences,” she says. “That’s what COVID did.”

Which brings us to Goldworm’s field of expertise: helping brands understand how the scent of their product or store (or hotel or plane) makes customers feel, and formulating accordingly. “We’re looking at all the products that you’ve used over the last year—antibacterial soaps, hand sanitizers—and figuring out which ones made you feel comfortable and safe early on but later are going to give you PTSD.” She’s working with airlines, for instance, to think about the cleaners they use, and advising them to avoid the scents we all now associate with tension and paranoia. She and her sister, Samantha, also just launched Scent For Good, a fragrance brand with a philanthropic arm that works with hospitals to neutralize their olfactive environment.

“We’re looking at all the products that you’ve used over the last year and figuring out which ones made you feel comfortable and safe early on but later are going to give you PTSD”

It’s not about having people remark on how good a place smells—they likely won’t even realize it’s scented, says Goldworm—but about preventing their parasympathetic nervous system from being triggered by negative scent associations. That’s why she’s currently encouraging clients to consider a “transitional scent” that can be swapped out when this is (hopefully) over. She’s applying that advice to her own life, too. On the first day of 2021, she tossed all her cleaning supplies and swapped them with products that smell radically different. “Anything that has a smell linked to last year, get rid of it,” she says, “and you’ll immediately feel fresher.”

“Anything that has a smell linked to last year, get rid of it and you’ll immediately feel fresher”

In my case, that might mean putting my precious Glossier You on hold a little longer and searching for a scent that suits this tentatively optimistic moment. It could also mean wearing perfume for a reason beyond the performative, “I like it when strangers in restaurants compliment me” impulse I’ve realized is my fragrance MO.

“We all wear fragrance for different reasons,” says El Masri. “You can wear it because you like to be told you smell good. Or you can wear it to seduce. But another reason is for self-love, to feel good.” That’s a feeling I think we’d all like to spritz liberally right about now.

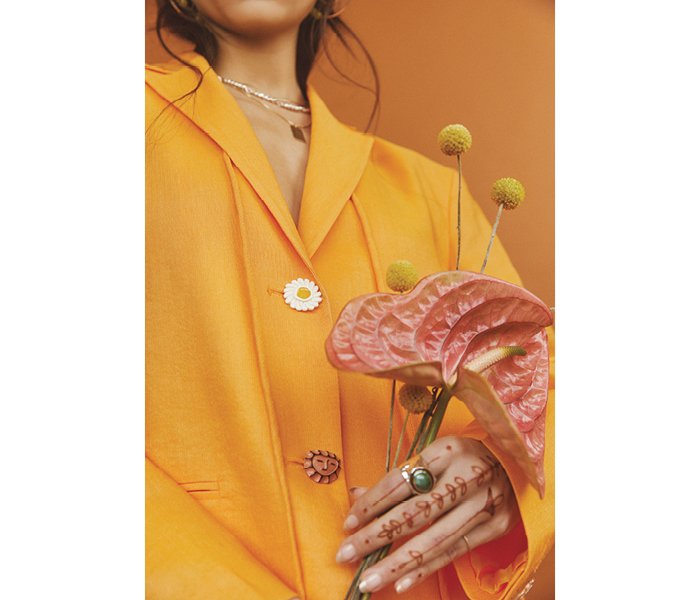

Styling by Olivia Leblanc, hair and makeup by Vanessa Ashley, flowers by Bell Jar Botanicals.

Main image: Cecilie Bahnsen dress, $1,125, ssense.com. Ora-C earrings, $230, necklace, $390, ora-c.com. Sofia Zakia necklace, $728, sofiazakia.com

Source: The Many Ways COVID Changed Our Relationship to Smell