IBM gained notoriety after its artificial intelligence supercomputer Watson crushed its human competitors on the question and answer game show Jeopardy! more than a decade ago. But now the 111-year-old technology company is hoping to answer a tough question of its own: Can it give computers a sense of taste?

Four years ago, researchers at IBM set out to answer this question, starting first with a liquid that is largely free of taste and can be difficult for a human to tell apart: water. After the computer became familiarized with different water samples that had slight variations in composition due to their mineral content, it was put up against human competitors to see who could better identify a water sample it had seen before. The computer won.

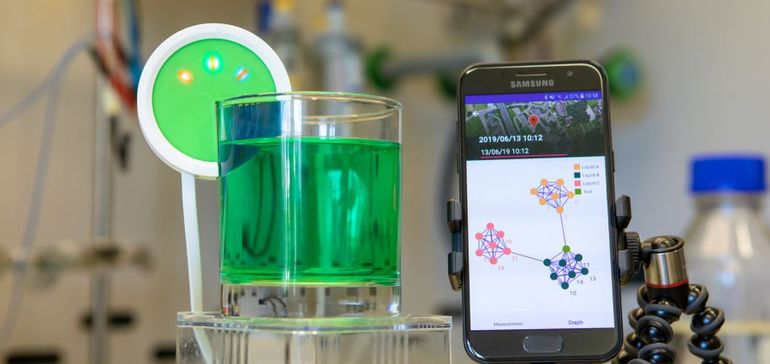

“The [artificial intelligence] system was better than our human tasters at distinguishing specifically four different kinds of mineral water,” said Patrick Ruch, the lead researcher on IBM’s artificial intelligence-assisted e-tongue technology called Hypertaste.

The circular-shaped disk undergoes its “taste test” by creating a digitized chemical composition of a liquid it has sampled. The “fingerprint” is then compared with other liquids in a database using artificial intelligence — a process that takes less than a minute — to identify a match.

While Hypertaste is still a few years away from widespread commercial use, IBM is working with industry partners on different applications for it. These include collaborating with food and beverage companies to capture and predict different kinds of flavors, and to quickly identify coffee, soft drinks and other offerings that would resonate with consumers.

“The [artificial intelligence] system was better than our human tasters at distinguishing specifically four different kinds of mineral water.”

Hypertaste is not meant to replace human experts, Ruch said, but rather to offload some of the most mundane or difficult tasks, like repeated taste testing of a product, to ensure quality remains the same from batch to batch. It also can be used to ensure authenticity, such as sussing out counterfeit wines or whiskeys, or to assist in product innovation by discovering new and different flavors.

Future applications for the technology could include finding contaminants in drinking water, tracing raw materials throughout the supply chain and checking for the presence of foodborne illnesses.

“The more people that are using it and can benefit from it and feed the data back into it, the better the technology will get,” Ruch said.

Artificial intelligence is an increasingly popular tool for food companies. With countless bits of information and pressure to innovate and get products to market faster, companies are no longer just relying on traditional methods of R&D and testing.

McCormick & Co. partnered with IBM three years ago to comb through data faster and more effectively by knowing which ingredients work together or which ones can be used as substitutes for each other. McCormick has introduced eight products so far created with the help of artificial intelligence.

It allows “our product developers to explore flavor territories more quickly and efficiently to learn and predict new flavor combinations across sensory science, consumer preference and flavor palettes,” the company said in an email.

Conagra Brands, the maker of Healthy Choice, Reddi-wip and Slim Jim, also uses artificial intelligence-enabled platforms to identify consumer preferences and release on-trend products to market in a fraction of the time. Brightseed and dairy giant Danone North America announced a collaboration in 2020 to use artificial intelligence to unlock hidden nutrients in soybeans.

A ‘major’ competitive advantage

The average human tongue has up to 8,000 taste buds that help distinguish the five tastes of sweet, sour, salty, bitter and umami. But how people actually taste the food is heavily influenced by the human nose. Not surprisingly, the two senses are closely connected. For example, the taste buds on the tongue determine if a food is sweet, while the nose determines what that sweet is connected to, like a strawberry or a grape.

Biotechnology company Aromyx estimated that while the average human nose can distinguish a trillion different odors, it often has difficulty deciphering the difference between these smells and tastes.

To solve this problem, Aromyx has turned to artificial intelligence. The company has cloned receptors found in the nose and tongue. Scientists then place something a consumer might taste, like a drop of coffee, on those cloned receptors before measuring how much they turn on — in effect replicating the reaction that occurs in the brain when a person takes a sip of his or her morning brew.

“The ones we’re working with definitely view this as a major competitive advantage for them.”

The process, done millions of times over, allows Aromyx to assemble a database for an outside R&D team to use when testing coffee. Based on how those receptors react in the future, a CPG could determine if consumers will enjoy a similar kind of coffee; how their reaction might differ based on things like demographics or even where they live; and why the person does or does not like it — say, because it has a floral flavor or a certain ingredient.

“Now, suddenly you can put that into numerical terms and make targeted recommendations around what products people would like, why they would like it and how to fix your product, how to make them taste better, or smell better to a particular group of people,” said Josh Silverman, Aromyx’s CEO.

Aromyx’s database can detect the flavor and suggest what needs to be tweaked, and determine the ingredients that should be added or subtracted for that to happen.

Silverman said one of the most popular uses for his platform is in sugar reduction. Many CPGs are reformulating ingredient mixes to cut back on the popular sweetener while working to maintain the same flavor found in the original product. Aromyx’s database can detect what chemicals need to be changed once sugar is removed to get back closer to the original taste.

Silverman compared it to paint at a hardware store, where color is universal regardless of the location. Each location uses a machine to measure the customer’s desired color and then to determine how much of each dye is needed to create that specific color by controlling the amount of red, green, and blue wavelength reflected by the paint.

“Instead of doing random trial and error or random walk through the chemical space, they actually have a direction, right?” he said of food companies. “They know what ingredients to change by how much. They can work their way intelligently towards the final solution instead of randomly. And that insight is hugely valuable to them.”

The process, he said, can save millions of dollars in development costs while getting products to consumers faster — a huge advantage in a food space where competition is fierce and consumer trends are rapidly shifting.

An estimated 30,000 new food and beverage products are launched every year, and despite exhaustive research and testing spanning several months and years, the majority of them do not succeed. Nielsen found 85% of products in the CPG category typically fail within two years, providing companies with an impetus to look for new ways to give themselves any advantage they can.

“Large companies have realized how much money they are wasting on failed product launches. It comes back to a recognition that their internal data is just not accurate,” Silverman said. “If we can give them that same level of data on if the customer will like it or not without having to do the whole launch, market test, … bring it back in house, redo it, all those things are hugely valuable to them. That certainly has been a good selling proposition.”

Silverman said revenue at Aromyx has doubled each of the last three years, and the company closed its first Series A funding round at $10 million last summer to help it increase output. Business has been so brisk that the company is getting more business than it can handle, with a six-month backlog for new customers.

Silverman declined to say which food and beverage companies Aromyx is working with to protect any first-mover advantages they may have in the marketplace. Many of Aromyx’s customers, he said, are hesitant to publicly acknowledge they are even working with his company.

” ‘We don’t want to tell our competitors we’re doing this because then they’ll start doing it. We don’t want you to get more popular, ‘ ” he said, citing discussions he’s had with his customers. “The ones we’re working with definitely view this as a major competitive advantage for them.”

Source: Taste testing taps into the modernized speed of artificial intelligence | Food Dive