Every city is a complex environment, bringing together people, cultures, architecture, commerce, and even nature. While experiencing a city, a lot of attention is given to its appearance, but appearance is not everything. The theory of sensory design aims to go beyond vision and explore the richness of the built environment through textures, smells, and sounds. For city officials and planners, a lot of attention generally goes towards how a city looks and sounds, but in terms of smell, the focus is mainly on managing waste or cleaning unsanitary areas. Yet the sense of smell, so often overlooked, is strongly linked to the creation of emotional memories. It contributes to our understanding of the world; it reveals otherwise hidden cultural practices, and it rounds up the experience of an environment.

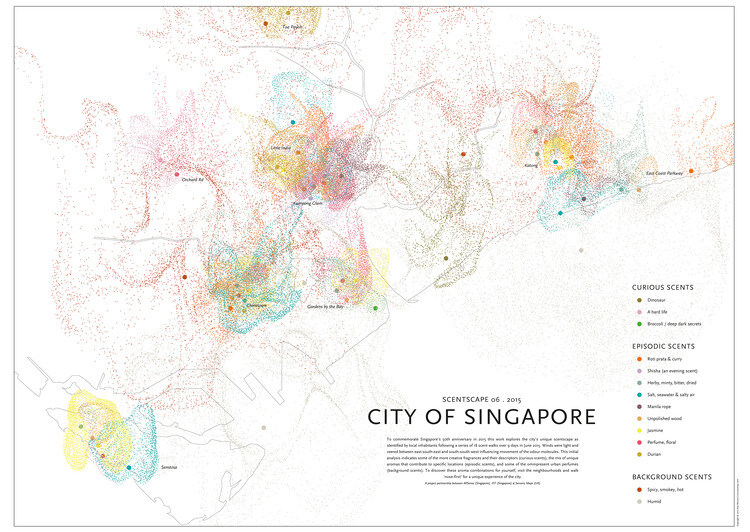

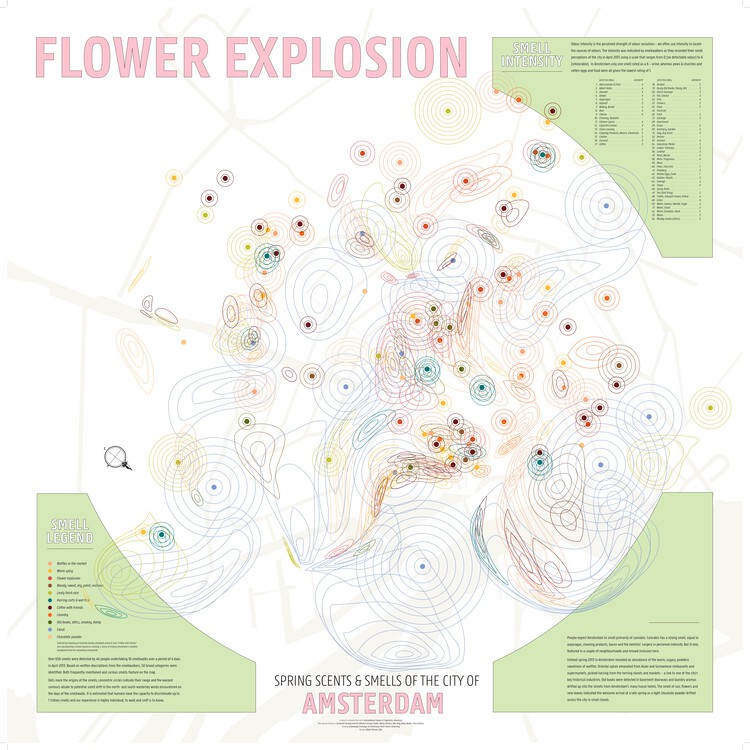

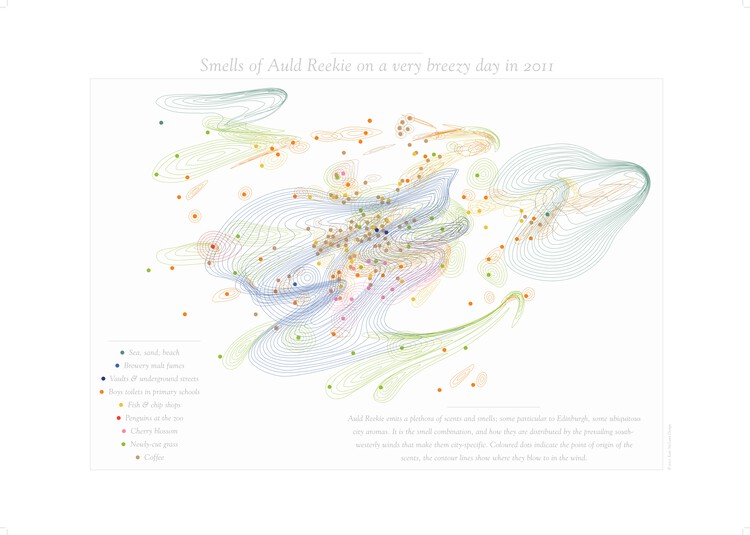

Researcher Dr. Kate McLean aims to celebrate the role smell plays in city life by mapping the “smellscape” of a city. The word smellscape is used as an equivalent to the visual landscape, yet its qualities are more ephemeral, based on individual or collective perceptions at a specific point in time. As an artist and course leader for Graphic Design at the School of Architecture, University of Kent, UK, McLean has spent the last decade surveying the smellscapes of different cities and translating their sensory qualities into maps. While these maps can only represent a time-specific instance, they are a glimpse into the abundance of information that smells can reveal about a space.

Human olfactory perception contributes to our understanding of the world; people delight in localized scents and feel disgusted at de-contextualized odors. Slight whiffs can enable the pre-visualization of a forthcoming activity, serve as a summary synthesis of previously-witnessed events and have the capacity to evoke situated memories. However, the smellscape is in constant flux, and ephemeral, volatile smells are easy to ignore when experienced by ordinary people in everyday, urban environments. – Dr. Kate McLean

Dr. Kate McLean’s approach employs the practice of mapping to underline the role of odor as a place-making element and component of the public space. McLean leads scent walks for every city investigated as the source for all mapping practices. Small groups of people are guided to move through the city, focus on the olfactory simulants and describe what they are feeling. The collected data is then synthesized into a smellmaps, beautiful visual translations of the perceived ‘smellscape’ in each place.

The resulting process is not only helpful in documenting hidden aspects of a city, but many participants describe the process as being transformative. During the first walks, the researcher expected people to offer objective descriptions, like the aroma of coffee near coffee shops. Yet some of the answers underlined the emotional connections people create with scents: some of the unusual descriptors include the “smell of shattered dreams”, “broccoli / deep dark secrets” and “a hard life”. These are proofs of the complex odors combining several elements at every moment.

When exploring Amsterdam in the spring of 2013, the descriptions offered subverted the expectations. Besides the city’s notoriously famous odor, the 44 volunteers identified over 600 perceived scents, some belonging to the city and others more in line with expectations of walks in the countryside. Over the warm powdery sweetness of waffles, oriental spices emanated from Asian and Surinamese restaurants, and pickled herring from the herring stands and markets, a link to one of the city’s key historical industries. Old books were detected in basement doorways and laundry aromas drifted up into the streets from Amsterdam’s many house hotels.

The smellmaps are a way to facilitate discussion and raise the awareness of communities. They represent key indicators of human activity. The perception of the stimulus depends on the context, we might enjoy the smell of seafood in a fish market, but find it disconcerting if we encounter it in a park. As most smells are the result of human activity, paying attention to these aspects can also speak about the cultural practices within the neighborhood, from culinary traditions to the prevalent type of industry or favorite pastimes.

This user-centered approach builds on the works of others in the built environment community. The first recorded smell walk was recorded in 1790 in Paris by Jean-Noël Hallé. His ten kilometers walk along the Seine was a sanitary survey in order to investigate its noxious smells, which were thought at the time to be a direct cause of disease. The memoirs of Jean-Noël Hallé are explored in Alain Corbin’s classic study of smells and their perception published in 1982. Then, three decades later, Victoria Henshaw began discussing smell as something integral to urban planning and design. Currently, UCL researcher Cecilia Bembibre is working with Kate McLean to develop methods for archiving smells through both visual and chemical techniques.

Moving from odor nuisance control to smellscapes opens up opportunities to appreciate the benefits of smells in human experiences and well-being. Part of understanding the world more holistically, smells, either negative or positive, should be considered an essential aspect of the design and planning framework of public spaces alongside other sensory components. If nothing else, thinking about the way a city smells could help preserve its uniqueness and deepen our experience of neighborhoods.

This article is part of the ArchDaily Topics: Cities and Living Trends. Every month we explore a topic in-depth through articles, interviews, news, and projects. Learn more about our ArchDaily topics. As always, at ArchDaily we welcome the contributions of our readers; if you want to submit an article or project, contact us.

Source: Sensory Maps: What the Sense of Smell Can Reveal about Urban Environments | ArchDaily