Is THIS the key to restoring loss of smell? Scientists are developing an implant that zaps the BRAIN when it detects odours

- New implant that zaps brain is being created to restore people’s sense of smell

- Scientists say prototype is similar to cochlear implant used to improve hearing

- Device is being developed by researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University

- It could give hope to millions, as five per cent of people suffer from loss of smell

Whether a person has lost their sense of smell from Covid, a traumatic brain injury or invasive surgery, scientists hope they may soon have a way to fix it.

That’s because they’re developing an implant — similar to one currently used to improve hearing — that zaps the brain when it detects odours and brings back a person’s ability to smell.

It is only a prototype at the moment, but if successful the breakthrough could give hope to millions, as figures estimate up to five per cent of people worldwide suffer from the debilitating condition.

Scientists at Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) are currently working on the revolutionary device, which is based on a cochlear implant used to improve hearing.

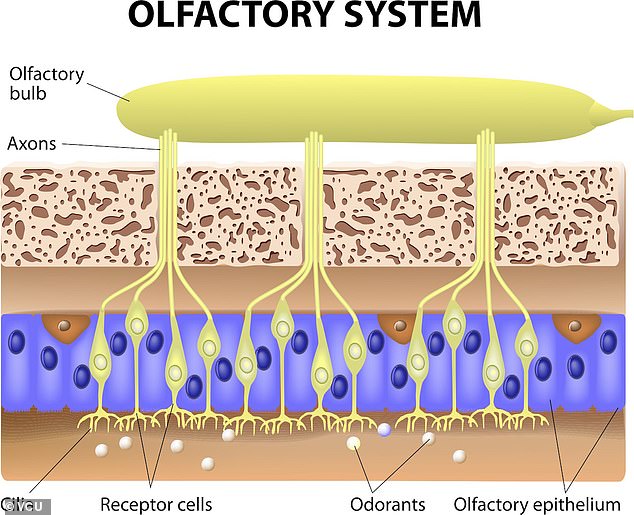

Loss of smell, known as anosmia, occurs when the nerves in the olfactory bulb are damaged, meaning they no longer transfer smell information to the brain.

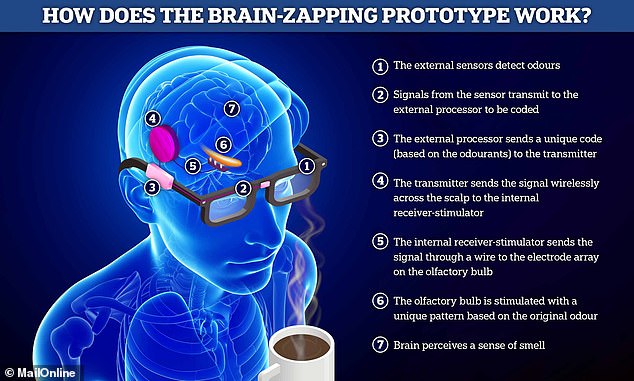

Scientists are developing an implant — similar to one currently used to improve hearing — that zaps the brain when it detects odours and brings back a person’s ability to smell (pictured)

A working prototype is pictured which shows a small gas sensor sitting near the nostrils. This would be mounted on glasses or another holding device and once the gas sensor comes into contact with odours, sensory information would be sent to an external processor. The information is then delivered to an internal electrode array, which stimulates the olfactory bulb

For many years, neurophysiologists have been challenged by the difficulty of patients who lose their sense of taste and smell because of the complexity of the olfactory nerve system.

With the hope of offering a solution, neurophysiologist Professor Richard Costanzo and his colleagues have been working in VCU’s Smell and Taste Research Laboratory to develop a prototype device that could restore damaged olfactory functions.

‘Over the last two or three decades I have been finding a way to restore the sense of smell,’ said Professor Costanzo.

‘Five to ten years ago, I had this idea that we could bypass the olfactory nerve damage — like in a cochlear implant that stimulates parts of the brain, to restore perceptions of smell — so the people who are suffering would have some sort of way of restoring it.’

After Professor Costanzo and his colleague, cochlear implant surgeon Dr Daniel Coelho, crossed paths with a wealthy donor, it led to the formation of the company Sensory Restoration Technologies.

The donor was Scott Moorehead, who suffered a traumatic brain injury and anosmia in a skateboarding accident.

Moorehead fell in the driveway of his home in Indiana while teaching his then six-year-old son, Mason, how to skateboard.

It left him with concussion and internal bleeding, and also severed the connection of the olfactory nerves in his nose to his brain.

Financial backing from Moorehead, who is CEO of The Cellular Connection, the largest Verizon retailer in the US, helped the scientists produce the Olfactory Implant System (OIS) — a prototype brain stimulation device designed to restore a person’s sense of smell.

Professor Costanzo said: ‘We patented an idea for how to create an array of sensors that would create a smell fingerprint — so a computer would have a specific code for every smell.

‘And you would train this device with different odours to have unique fingerprints for those odours.’

He went on to explain how similar the device would be to a cochlear implant.

It is only a prototype at the moment, but if successful the breakthrough could give hope to millions, as figures estimate up to five per cent of people suffer from anosmia (stock image)

‘No one knows where in the brain the sense of smell is for a banana or an apple and it may not even be in one place.

‘But with cochlear implants, once they’re inserted to get the different sounds and frequencies to produce speech, we can individually program those for each patient,’ said Professor Costanzo.

‘So we envisioned the same approach for the olfactory implant to embed the electrons in specific areas of the brain and after asking the patient what things smell like, we can programme it to match up to a digital footprint.’

To figure out where in the brain the implant should be placed, the researchers piggy-backed onto a 24/7 epilepsy monitoring study, stimulating the patients with different odours while they were being observed.

By doing this, they were able to pinpoint what part of the brain was being stimulated by the smells.

Neurophysiologist Richard Costanzo (right) and his colleague Dr Daniel Coelho (left), have been working to develop a prototype device that could restore damaged olfactory functions

Smell works when odour molecules enter the nasal cavity and make contact with olfactory receptors. Nerves called axons then carry sensory information to the olfactory bulb, which processes the information before it’s delivered to more complex brain regions (pictured)

Professor Costanzo said: ‘On the back of this study, we will develop electrodes that go into the particular areas of the brain to stimulate them then we can hook them up to our computer to restore the sense of smell.’

Andrew Lambert, from Sussex, who suffers from a loss of smell, is just one of the people who could benefit from the new device.

The 66-year-old company director at ClearChain lost his sense of taste and smell after undergoing invasive brain surgery when a tumour in his sinus popped a hole through his skull into the brain.

When asked how his condition affects his day-to-day life, Mr Lambert said: ‘I suppose the best way to describe it is that I’ve had dimensions removed from my life and it makes some aspects of my life less enjoyable, while creating unconscious uncertainties.

‘For example, before Covid, I went up to a meeting in London. I came out of Oxford Circus station and it was raining.

‘I had a momentary feeling of panic because I couldn’t smell what you would normally smell like ozone, I suppose.

‘Because I couldn’t smell anything, it felt like I had walked into a shower coming out of the station.’

For Mr Lambert, undergoing a procedure to implant Professor Costanzo’s device would not only help him identify everyday dangers such as smelling gas, but also give him the chance to participate more in social events.

He said: ‘My other senses have been trying to compensate when identifying the texture of food. Memory for me is a very important way of coping, so if I eat something I’ve eaten before, I remember how it tastes and I can get a tiny bit of enjoyment from it.

‘But with the implant, it would mean that the elements of enjoyment would come back and the uncertainties I have would diminish if not be removed and I wouldn’t have to worry about them anymore.

‘I would also be able to join in with things I can’t currently join in with — like eating out — I can only be an observer, but I could actually be a participant in those events more fully.’

Professor Costanzo explained what happens when the olfactory nerve system is damaged.

He said: ‘The nerves go directly into the brain and when they’re cut, the brain tries to protect itself by causing scarring to protect the damaged tissue, which then prevents any regenerating nerves from getting back to the brain.

‘We can’t yet repair the nerves but if we can map the areas of the brain, we can optimally generate a perception of a smell.’

The professor said that after years of giving patients the news that there is no cure, he and his team are excited about the future.

‘This century, or the next century, we’re going to see the advances in microelectronics, applied to write interfaces, in many different applications,’ he added.

‘The technologies are advancing technologies and microcomputers have chips that are so small that it’s all coming together in a good way.

‘I think there’s some interest in Europe as well as the US, but I’m sure that other countries will probably jump on the bandwagon of our technology as soon as they can.

‘I think the more people that work on this, the better off our solution will be for the patient population.’