Researchers from Boston University’s Center for Systems Neuroscience revealed how much power scents have in triggering the memory of past experiences and the potential for odor to be used as a tool to treat memory-related mood disorders. The new study was published in the Learning and Memory journal.

During their study, the researchers found that if odor could be used to elicit the rich recollection of a memory, they could take advantage of that therapeutically.

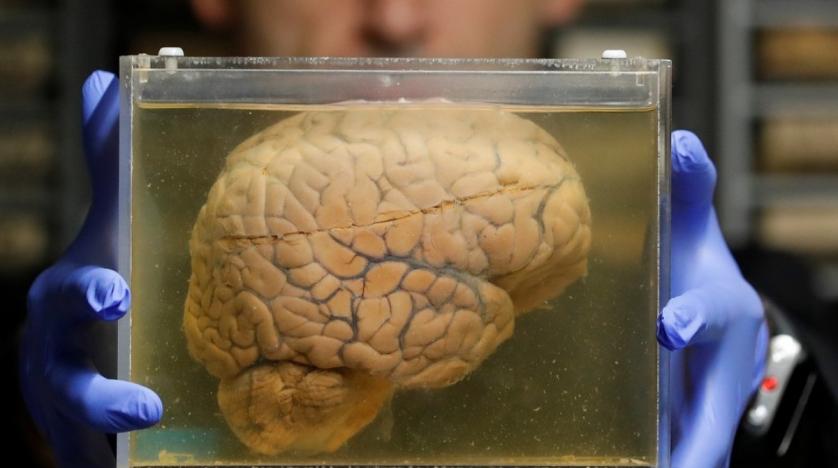

The traditional theory suggests that our memories start out being processed by the hippocampus, an area in the brain that infuses with rich details. Over time, especially when we sleep, the set of brain cells that holds onto a particular memory reactivates and reorganizes. The memory then becomes processed by the front of the brain, the prefrontal cortex, instead of the hippocampus, and many of the details become lost in the shuffle.

This theory explains why our memories tend to get a bit fuzzy as time passes. It also helps explain why people with hippocampal damage are often unable to form new memories while their ability to keep old, prefrontal cortex-stored memories remains perfectly intact. However, critics of this theory maintain that it doesn’t tell the whole story, as scents, which are processed in the hippocampus, sometimes trigger seemingly dormant memories.

To answer these questions, the research team created fear memories in mice by giving them a series of harmless but startling electric shocks inside a special container. During the shocks, half of the mice were exposed to the scent of almond extract, while the others were not exposed to any scent.

The next day, the researchers returned the mice to the same container to prompt them to recall their newly formed memories. Once again, the mice in the odor group got a whiff of almond extract during their session, while the no-odor group was not exposed to any scent. But this time, neither group received any new electric shocks.

Consistent with the traditional theory, both groups exhibited significant activation of the hippocampus during this early recall session. However, during the next recall session 20 days later, the researchers were in for a shock of their own. As expected, in the no-odor group, processing of the fear memory had shifted to the prefrontal cortex, but the odor group still had significant brain activity in the hippocampus.

Source: Scents to Treat Post-Traumatic Mood Disorders | Asharq AL-awsat