Diminished hearing and sight can have a sweeping effect on your day-to-day life: You may struggle to participate in conversations, drive, recognize friends from far away, and find many other everyday activities out of reach.

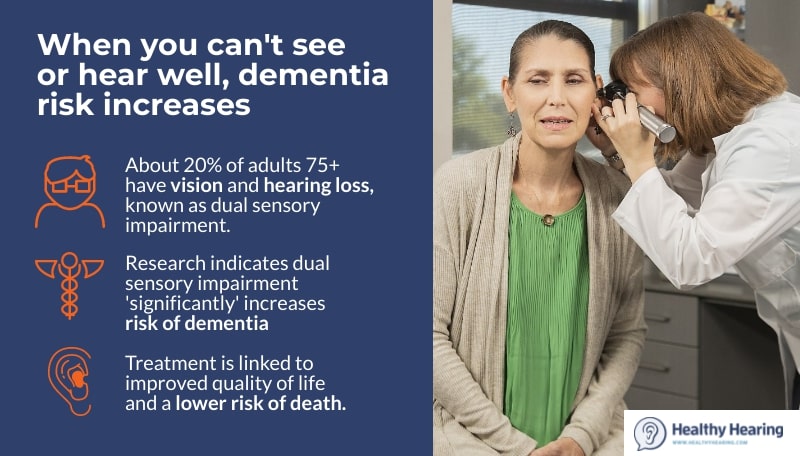

There’s also a big-picture concern: Along with a known connection between hearing loss and dementia, recent studies show that when people have both vision and hearing impairment—what’s known as dual sensory impairment (DSI)—their risk for dementia increases significantly.

“There’s been a number of research studies,” says Harvey Abrams, PhD, a longtime audiology research expert who now works for the hearing aid company Lively. “Across all of them, I think that the results are fairly compelling that dual sensory impairment poses a greater risk than either impairment [alone],” he says.

One recent standout finding: A person with DSI has an eight-fold increased risk of dementia, according to a May 2022 study in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease Reports.

If you or a loved one have both untreated vision and hearing impairments, what should you make of these findings? Read on for what’s currently known—and what remains to be discovered.

Why might dementia and sensory impairments be connected?

Researchers know there’s a connection between sensory impairments and dementia, but the cause of that link remains unknown. That said, there are credible theories around the “why” behind the link—the most common ones are:

- Common cause theory: There could be an underlying problem—such as a vascular disorder affecting blood flow to both your brain and your ears—that leads to both sensory and cognitive impairments. The theory here: The same underlying problem leads to two impairments, Abrams explains.

- Cognitive load theory: “As you get older, you suffer some cognitive decline,” Abrahms says. That means you have less resources available when you need to hear in a noisy environment or process a lot of visual information, he says. With the theory, the hypothesis is that if you have hearing loss, your brain then makes additional effort to help you listen, depleting your overall cognitive resources.

- Cascade theory: Losing hearing or vision abilities can make people withdraw from relationships and cut down on their physical activity. That makes sense: Why attend the theater with a friend if you won’t be able to hear the actors, see the set, or easily talk to your friend? This can have sweeping effects. “Hearing or vision impairment may lead to behaviors and lifestyle indicative of a higher risk for dementia,” per commentary in JAMA Open Network.

- The “harbinger” hypothesis: This is also sometimes referred to as overdiagnosis. The idea behind this theory is that if you can’t fully hear or see instructions, you may not perform well on tests to assess your cognitive abilities.

“It makes sense that having problems with both senses create greater risks,” Abrams says. With the cognitive load theory, for instance, it’s clear that two diminished senses adds more burden to your brain’s resources. Or alternately, it could make following the instructions and responding to questions in a cognitive test that much more challenging.

What research says about DSI and dementia

As Abrams points out, there have been many studies examining DSI and cognitive decline.

They don’t all use the same methodology—nor do they always have the same results, he notes. They may, for instance, define a hearing or vision impairment differently, or look at different populations. In general, though, “impairment” meant a person struggled to see or hear, even if they wore glasses and/or hearing aids.

Here’s a look at some recent standout findings:

The May 2022 study published in JAMA Network Open found “dual sensory impairment was associated with a 160% increased risk for all-cause dementia and a 267% increased risk for Alzheimer disease.”

There were almost 3,000 participants in this cohort study, and they self-reported if they had a hearing impairment or visual impairment. (If people wore hearing aids or glasses, but still couldn’t do everyday activities—like talk on the phone or drive—they were instructed to say they had an impairment.)

Worth noting: While having dual sensory impairment was associated with a risk for dementia, there was also a significant association with a single sensory impairment, per the study.

The Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease Reports examined data drawn from the American Community Survey, which includes more than 5 million older adults aged 65 or older. This analysis revealed for these older adults, sensory impairments upped their risk for cognitive impairment—a hearing impairment led to more than double the risk, while a vision impairment led to more than triple the likelihood of a cognitive impairment. Most dramatic of all: Older adults with DSI had an eightfold uptick in risk for cognitive impairment.

In this study, as in the one above, impairment was self-reported. For cognitive impairment, people were asked to give a yes or no answer to this question: Because of a physical, mental, or emotional condition, does this person have serious difficulty concentrating, remembering, or making decisions?

Similarly, a June 2022 cohort study in Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, which looked at more than half a million people in the UK also found that participants with vision impairment had a 50 percent higher risk for developing dementia, while people with a hearing impairment had a 42 percent higher risk. Highest still was the risk for developing dementia in people with dual sensory impairment: 82 percent.

A note on what studies reveal—and their limitations

“Statisticians are my heroes,” Abrams says.

That’s because they’re able to eliminate factors that could potentially increase a risk for dementia (think: education, BMI, education, age, and so on) from the data. That allows researchers to shine a light on the impact of sensory impairments, without other potential dementia risk factors swaying the results.

Still, studies have limitations. In fact, if you read write-ups, there will nearly always be a section detailing them. For instance, could self-reporting around impairments undercount their severity? Are there other factors that aren’t accounted for?

Plus, it’s important to note that researchers have found a statistically certain connection—but not a causal connection, Abrams notes. That is, dual sensory impairment and dementia are linked, but it’s not clear that these impairments cause dementia to occur.

Not known yet if sensory impairment causes dementia, just that there’s a link

It’s also not clear how much eyeglasses and hearing aids lower the risk.

“Future research is also needed to examine how standard treatments for hearing and vision impairment, such as hearing aids, may influence cognition,” noted the Alzheimer’s Disease Reports authors.

Finally, Abrams notes that everyone—both people with and without sensory impairments—has a risk for dementia. What’s revealed by recent studies is that your relative risk for it is higher if you have a sensory impairment, and higher still if you have two sensory impairments, he explains. Dementia could occur if you have DSI, or might not. “It’s just that you have a higher risk” compared to someone without sensory impairments, Abrams says.

Think about it this way, Abrams says: Wearing a seatbelt reduces your risk of injury or worse in a car accident, but doesn’t eliminate it. And, some people who stubbornly refuse to belt in never experience harm from a car accident. Their risk is higher, but it’s not set in stone.

What can you do if you have hearing and vision impairments?

First off, it’s always better to know, Abrams says.

It’s helpful to be aware that there’s “a risk associated with hearing loss, vision impairment, and that that risk is greater with both and either alone,” he says.

That’s true for patients—and doctors, too.

To an audiologist, everything is an ear, while to an optometrist, everything is an eye, Abrams points out. But these studies show that both specialists would benefit from making referrals and explaining the heightened risk of two sensory impairments to patients. And, practitioners testing for dementia and cognition might want to confirm that sensory limitations are not distorting patients’ results.

An awareness of the connection between sensory impairments and dementia may motivate you to be vigilant about checking your hearing and vision, and taking advantage of treatment options. After all, research indicates that treating hearing loss, for instance, may decrease cognitive decline.

The importance of treatment

If you or a loved one are noticing changes in your vision and hearing, schedule an appointment with a medical professional, If you are diagnosed with dual sensory impairment, work closely with your medical team to identify appropriate assistive devices, coping strategies and other rehabilitation activities to address your individual needs. Most importantly, engage the help of your loved ones in the education and rehabilitation process.

Combined with other health issues associated with aging, dual sensory loss can seem overwhelming, said Dr. Ying-Zi Xiong, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow at the Gigi & Carl Allen Envision Research Institute in Wichita, Kan. (ERI) and a research associate at the University of Minnesota.

The good news: Studies show that people who receive treatment for dual sensory impairment have a higher quality of life and a lower risk of death than people who don’t receive treatment. You are never too old for hearing aids.

“Family support is crucial for older people who are dealing with dual sensory loss,” Xiong said. “We need to be patient when elders have communication problems and encourage and create opportunities for them to engage in social interactions.”

Source: In older adults, vision and hearing loss significantly raises risk of dementia