Canada’s cultural institutions need hip hop communities now more than ever. I say this after working as a guest curator at one of Canada’s most significant art galleries — the McMichael Canadian Art Collection — for its first-ever show on hip hop, “…Everything Remains Raw: Photographing Toronto Hip Hop Culture from Analogue to Digital.”

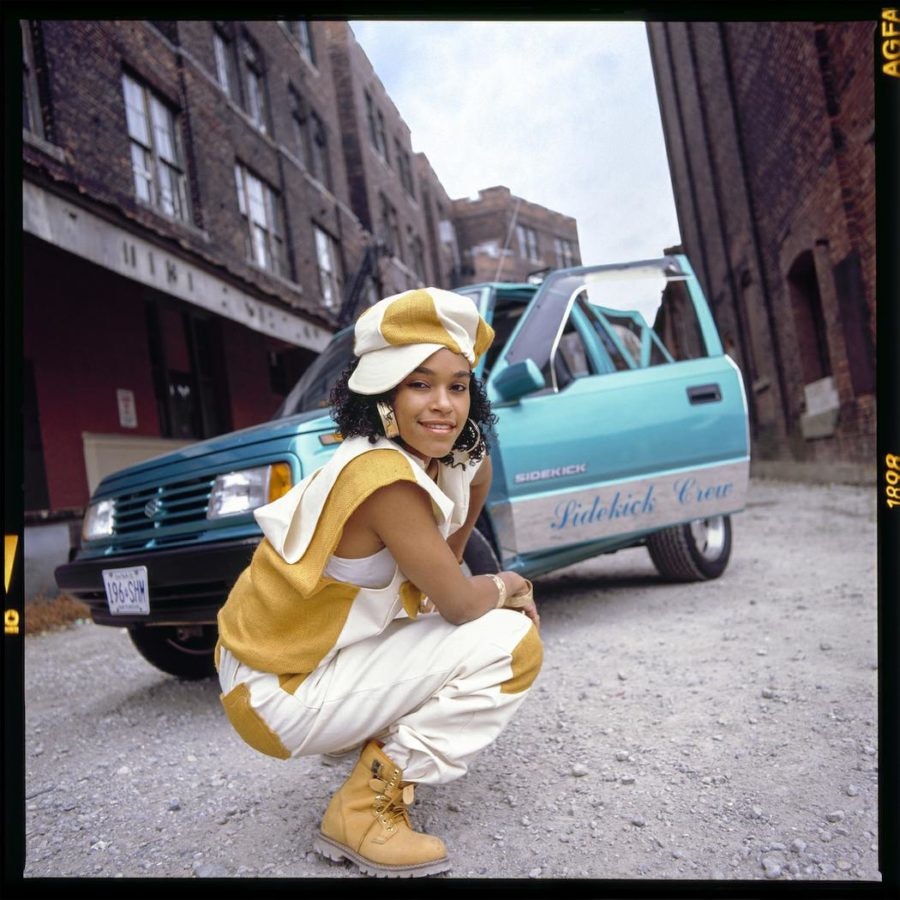

The exhibition, on display until Oct. 21, features Canadian photographers, graffiti writers, painters and video artists whose aesthetic renderings of life within Toronto’s hip hop culture in the 1990s and early 2000s are directly related to this country’s global billboard dominance today.

Hip hop culture, dismissed as fad when it first emerged out of New York City in the 1970s, has grown into a cultural phenomenon with global purchase power which translates differently in countries around the world, from France to Mongolia to Brazil.

Through mainstream media, we have been exposed to many nefarious images of Black criminality as well as images of conspicuous consumption.

The social critique and protest roots of this globalized and youth-driven art form, hip hop, provide some responses to these images and ideas.

One needs only to look at the trajectories of the Pulitzer Prize (awarded to Kendrick Lamar this year) or at France’s world-renowned Louvre (which accommodated the filming of The Carters’ music video) to notice that hip hop culture is doing more than entertaining the masses.

The dozen artistic classics Beyoncé and Jay-Z include in their lavish video for “Apes%$t”, range from the Mona Lisa to the Raft of Medusa. Their images are not just an art history lesson, but also, arguably, a rewriting of the aesthetic codes that denigrate Blackness while upholding whiteness as a beauty standard.

A necessary shift in cultural institutions

Hip hop is not just about rap music. This subculture also includes graffiti art, bboying/bgirling (aka breakdancing) and DJing. Hip hop is a multidisciplinary and multi-sensory art form.

Hip hop culture illuminates a way forward within Canadian cultural institutions’ growth, evolution and vibrancy. It may seem that the spontaneity and improvisation of hip hop — cornerstones of the culture’s innovative core threaded seamlessly throughout dance, djing, rhyming and painting — are structurally and policy-wise an impossibility within cultural institutions.

Yet, thinking about how to take hip hop culture seriously for public-serving organizations like schools, libraries and arts institutions, is a significant and necessary shift in values and operational practices within some of our aging institutions.

The exhibit is an example of how an important cultural institution can work with and for hip hop culture in a way that honours the culture’s innovative, multilayered and postmodern nature. Together, with the team at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection, we developed an intercultural competency.

This kind of remixed engagement with the works of the Groups of Seven and the thousands of other canonical visual art pieces is only possible with a generosity on the institution’s part to learn experientially about the new audiences they want to cultivate.

Our goal was to curate a group exhibition of a dozen artists from Black, white, Indigenous, Asian and mixed backgrounds in 2018 while staying true to the mission Robert McMichael imagined when he built his gallery in 1955.

Curating is like DJing

In order to accomplish the daunting task of curating a public art exhibition focused on the multiplicity Toronto hip hop, I relied on the skills and values I learned as a DJ.

For 18 years, I hosted and sometimes DJ’d with my team members Kareem, Martin and DJ Spontaneous. We used our research and taste-making skills to find, create and present original songs and remixes. We relied on interactions with callers, guests and the music itself. Spontaneity and improvisation were central to the process.

Many of these collaborative techniques became critical to the success of “…Everything Remains Raw.” We put diversity at the core and worked with the artists to help create an inclusive exhibition.

Diversity at the core

Through an improvisatory outdoor video works by Mark Valino (in collaboration with various dancers), I encouraged an appreciation of the work of Tom Thomson.

David Strickland’s Owl Series was opened up by Norval Morrisseau’s brightly coloured Thunderbird with Inner Spirit allowed for a glimpse into the usage of Cree, Haida and various other Indigenous symbols.

Sheinina Raj’s Ghost of Ghetto Concept (1998) and Elicser’s TDot Roof Tops (2018) both fostered a different appreciation of landscape and environment, one that speaks with and to works by A.Y. Jackson and Emily Carr, among others.

Hip hop as curriculum

Learning is key here as the gallery hosts hundred of schools each year, where elementary and high school students learn about Canadian culture through the paint brushes of people like Alex Janvier and Lawren Harris.

I learned more about Indigenous life in Canada from Indigenous artists like the painter and sound engineer David Strickland, Saskatoon’s Eekwol and the recently MTV Video awardee Dreezus, than the inadequate curriculum I grew up with in the 1980s and 1990s.

Their beats and rhymes are infectious and lure me to look through another window, to see a Turtle Island view of Canadian society, a world few non-Indigenous, settler Canadians know well.

My intercultural competency grows as I experience and enjoy their music, interviews and art.

The presence of these hip hop heads, next to the important works of art-world luminaries like Christi Belcourt, Leanne Simpson and Kent Monkman, are poised to make Canadians more informed and better stewards of the land.

Hip hop’s critical attention

It’s easy to consume hip hop as nothing more than entertainment. However, I believe we should strive to engage hip hop as a living and evolving culture that rhymes across national borders and flattens walls to create bridges of intercultural learning.

The harder work is to engage hip hop as a cultural ethos that refuses to solely entertain, extending a long tradition of Black art forms that predate the market and do double duty now as commodities and social critique.

Hip hop in Canada creates the possibility for more and better representations of all of our lives. For example, check out Montréal’s Yassin ‘Narcy’ Alsalman (formerly the Narcicystwhose music, which makes a guest appearance on Ottawa’s a Tribe Called Red’s track, “R.E.D.” illuminates a world of intercultural artistic adventures via Muslim, Indigenous and African American perspectives in hip hop.

Critical attention to, and appreciation of, hip hop artists’ work in Canada is not a magical solution for aging cultural institutions. Policies, budgets, timelines and all the fun stuff of cultural work complicate the work. But this is the work.

The work ahead to ensure cultural institutions reflect our contemporary society will take collaborative yet inclusive muscle, improvisatory poetics and intercultural competency.

From award committees to guest curatorial ingenuity, our cultural landscape can only benefit from spending time with the various innovations that has given hip hop culture its staying power and its consistently replenishing relevance in fashion, music, language and more.

Globally, hip hop culture can have an impact across a variety of geographic, political, linguistic and cultural borders.

If we envision hip hop culture as something other than the dynamic globalized intercultural force it has proven to be, we will miss an opportunity to develop new tools to negotiate our entangled, overlapping and intersecting cultural futures here in Canada.

Source: Hip hop paves the way forward