With “RE_______,” a fall exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Sissel Tolaas, a Norwegian artist, chemist, and linguist, the galleries put smell front and center.

“After having been [at the Astrup Fearnley Museet] for two weeks, I went back to Berlin and started to look into my archives,” Tolaas says of how the exhibit came together. “I had been doing that anyway during COVID, using the moment to rethink my work over the past 25 years, and especially now with this invisible reality becoming the main topic of concern.

“The fact that the world can close down over a matter you can’t see is indeed what my work is about.”

The title “RE______” refers to the complexity of the topics engaged in the exhibition. It could stand for “rethink,” “reality,” “remember,” “reveal,” etc., or be seen as a callback to her studio, dubbed “Research Lab.” But the “RE” prefix is significant for its flexibility and openness to interpretation.

The exhibit is arranged with great intention while remaining ambiguous enough for explorers to have individualized experiences. Visitors first encounter a mirrored wall of vials containing the liquid smell of money and sets an immediate tone for the exhibition; from the onset, it’s clear the exhibition’s purpose has more to offer than smelling for smelling’s sake.

One set of pieces is a trio of pipes that hang from the ceiling and pump vanilla smells into a pool. One is of pure vanilla, another is of synthetic vanilla, and another is vanilla found in processed foods—though, notably, none of these smells are labeled. The smells call attention to a variety of topics: commodification of vanilla, which has become increasingly scarce as a resource, but also the widely accepted delight people experience from vanilla that, Tolaas says, likely stems from the presence of a chemical compound found in vanilla that’s also in human milk and many baby formulas.

Her linguistic background also comes into play.

“You often hear ‘vanilla’ referring to something plain or boring,” Tolaas says. “But vanilla has a complex history. It is also one of the most loved smells in the world.”

Topics are diverse just as the world is diverse, she says. The upstairs gallery is themed around air and carries a smell of the western Norwegian shore carried through the air with fans that circulate when there is a storm happening in Norway. Elsewhere, there are 115 blocks and stones imbued with smells from her lab, meant to be an intimate experience for some to trigger memories or, for others, a social one, to prompt conversation. The underlying ambition with the smell objects—and more broadly in the exhibition—is to stress the lack of language we have for smell as opposed to sight.

“What does smell activate in you?” Tolaas muses. “Is it something you want to remember? Have you smelled it before? The conversation is around people’s stories activated by memory through smell.”

In the case of the liquid money vials, she says, the conversation is about how we code smells. Much like the smell of gas is understood as potentially dangerous, the smell of money is a social construct that evokes different associations.

Her early interest in smells, she says, stems from a fundamental question she began asking herself as both a chemist and a person: “What if my sense of smell became the way I understand the world?”

In the decades since, she’s spent countless hours thinking about this question while using her artistic practice to engage the public and find new questions to research.

Zoë Ryan, director of ICA, first met Sissel while curating a project about the smells of Istanbul. When she heard about the exhibition in Norway, she thought it would be a perfect fit for the ICA’s mission.

“It’s a pleasure to work with Sissel, and for us this is a way to build on what ICA has become known for, but with a different type of practice,” Ryan says. “And that’s exciting … It’s so much a part of our mission to do projects with artists who are working on underrecognized topics and ideas, but also we’re [at Penn] a lab of experimentation,” she says, noting the work of Penn researchers like Anjan Chatterjee, who studies neuroaesthetics in the Perelman School of Medicine; Jay Gottfried, the Arthur H. Rubenstein University Professor; and Ani Liu, a Professor of Practice in the Weitzman School of Design.

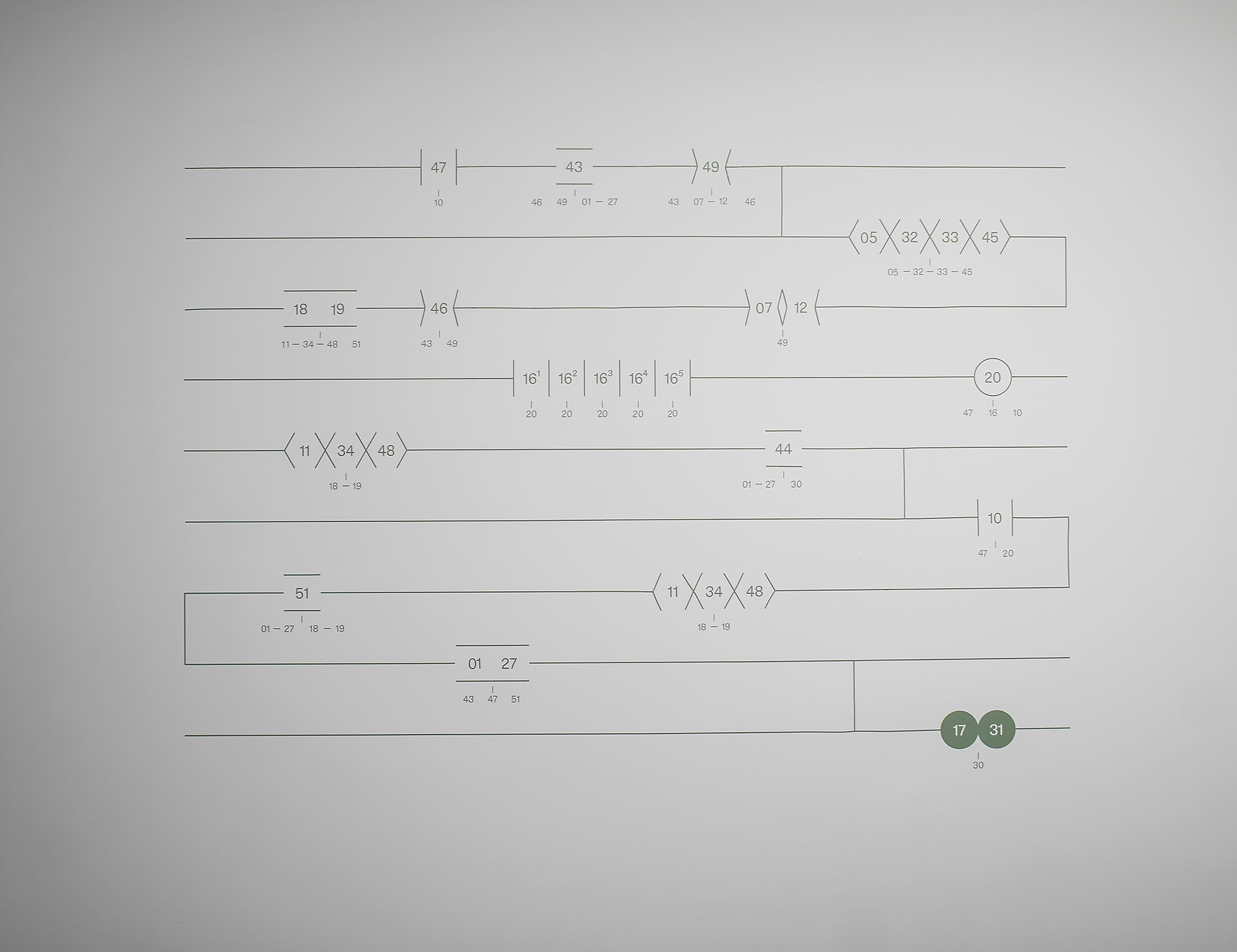

Rounding out the exhibit is a Reveal Room that uses a map that mixes a musical score with the Periodic Table. It’s organized so that visitors can collect codes while browsing the exhibition and later find more information about the smells—or complete the exhibit in the reverse order. Ryan also notes that docents will be on hand in the galleries to guide visitors through the experience.

While exiting the exhibition from the upstairs, sounds of reactions heard in the galleries will fill the air—think: every “Blech!” or “Oh!” of delight upon being struck by a remarkable smell, familiar or not.

“RE_______” opens Friday, Sept. 16, and an opening celebration will take place from 6-9 p.m. with a conversation between Tolaas, Ryan, and Solveig Øvstebø, executive director and chief curator at Astrup Fearnley Museet. The event is free and open to the public in-person and via Zoom.

Source: Exploring the depth of smell through art | Penn Today