Craig Jerome, a nurse practitioner in North Carolina, contracted covid two years ago. He lost his sense of smell and continues to experience anosmia. “Emotionally, it has created grief,” said Jerome, who misses cherished scents such as the Christmas tree smell that brings back fond memories of his childhood.

Richard Costanzo and Daniel Coelho hope their neuroprosthetic, which they call a “bionic nose,” can help Jerome and others like him.

It will, however, take five to 10 years for a fully developed prototype to be ready for implantation and testing in patients, said Costanzo, director of research for the VCU Smell and Taste Disorders Center in Richmond.

Costanzo said his idea for the device came long before the pandemic, born out of a desire to help people with a permanent loss of smell.

He began collaborating with Coelho, a surgeon and professor of otolaryngology, because the olfactory implant they are creating is similar in concept to a cochlear implant used to help Coelho’s patients hear.

The need for the device is greater now because of covid, Costanzo said, citing his research with Coelho and others. In their study of patients who reported anosmia after contracting covid at the beginning of 2020, 7.5 percent said they have not recovered their sense of smell two years later.

Covid has severely damaged the olfactory sensing cells in the nose for some patients, Costanzo said. “Without these cells, odors are not detected, and signals are not sent to the olfactory region of the brain,” he said.

In other patients, some of these cells recover and they regain partial sense of smell, “but often they are not normal, and individuals report distortions in smell perception, often unpleasant sensations,” he said.

Smell is important because it’s entwined with taste, which adds to the enjoyment of eating. Smell helps detect danger such as a gas leak or smoke from a fire. Emotions are also tied to smell; for example, we feel comforted by the unique odors of loved ones or joy from the fragrance of things such as flowers.

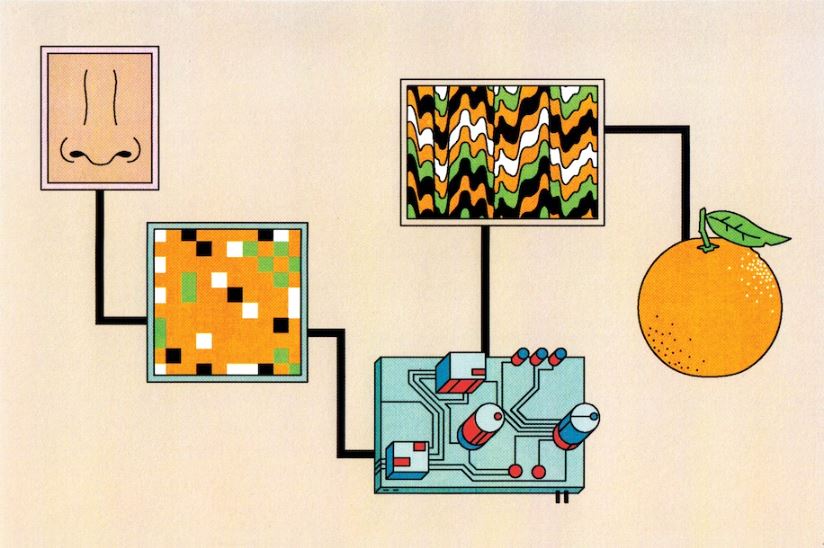

We are able to smell because specialized olfactory receptor cells in the upper regions of the nose detect chemical vapors in the air, Costanzo said. The cells send smell information through nerve fibers that pass through openings in the base of the skull and connect to a part of the brain called the olfactory bulb.

“The olfactory bulb shares this information with the rest of the brain, resulting in the perception of smell, such as the scent of an orange or fragrance of a rose,” he said.

Duplicating how we smell is uniquely challenging, Costanzo said.

For other sensory systems, he said, we know more about the stimulus and how receptors encode it. For hearing, the stimulus is pressure waves; for touch, it is mechanical deformation of skin; and for vision, it is electromagnetic light waves.

“The problem with smell is that we don’t know what physical properties of chemical odors are important for encoding all the different smells that exist,” Costanzo said.

Costanzo and Coelho are using microelectronics and computer processing, including artificial intelligence, to build their bionic nose.

Their strategy is to bypass the damaged olfactory cells and stimulate the brain directly with an implanted electrode array.

A small external odor sensing piece will send signals to a microprocessor chip which will generate “unique digital fingerprints for different smells,” Costanzo said. The chip will then relay the information via special radio wave frequencies to a receiver inside the skull to stimulate specific brain areas that generate a particular smell sensation or perception.

In their current prototype, both the odor sensing piece and the microprocessor chip are attached to an eyeglass frame, but they could be on other objects such as a wristband, Costanzo said.

Surgery would be required to insert the electrode array in the brain, though it’s too early to tell whether it would be placed by a neurosurgeon or endoscopically through the nose, Costanzo said. The researchers believe many people would accept this process, citing a small study of 61 patients with olfactory dysfunction, which showed that about a third said they were willing to undergo olfactory implant surgery to regain their sense of smell.

The research is funded through Lawnboy Ventures, a collaboration between Costanzo, Coelho and VCU’s Intellectual Property Foundation, who have a minority stake, and private investor Scott Moorehead. The company licensed the patent associated with the technology from VCU, Moorehead and the university said. Moorehead, who lost his sense of smell after a traumatic brain injury, said he joined the effort because he could potentially benefit from the device.

An early version of the neuroprosthetic was tested on rats. The researchers cut the olfactory nerves of the rodents and surgically placed an electrode array by the olfactory brain area. Costanzo said they were able to bypass the cut nerves and activate the olfactory brain cells.

“The rat could not tell us what they could smell, but we could record the electrical signals generated in the brain,” he said.

The researchers — collaborating with a former student of Costanzo, Mark Richardson — are now conducting human studies to map out specific regions of the brain that, if stimulated, could generate smell perceptions.

Richardson, director of functional neurosurgery at Massachusetts General Hospital, is studying epilepsy patients, who have electrodes placed in different regions of the brain to understand which areas are involved in seizures.

Those who agree to participate in the smell study are presented with different odors. Using recordings from the electrodes, the researchers are mapping brain areas associated with odor perceptions to determine the optimal sites for the olfactory electrode array.

“Figuring out how odor perception emerges from brain activity is a complex decoding problem,” Richardson said in an email, “but there may be multiple ways to re-create important aspects of smell for people with anosmia.”

The researchers also are planning studies to build a clinical version of their prototype that is safe and effective, they said.

“Hope is coming,” Coelho said. “There are a few important things that we need to get into place, but there’s very little reason to think that this device shouldn’t work.”

That is heartening news to Gregory, a New York City resident in his 60s whose last name is not being published to protect his privacy. He said he lost his sense of smell after a traumatic brain injury in 2005 and contacted Costanzo for help.

When he heard of this device, he cried, said Gregory, adding that Costanzo “gave me hope I could smell before I die.”

Source: ‘Bionic nose’ may help people experiencing smell loss, researchers say