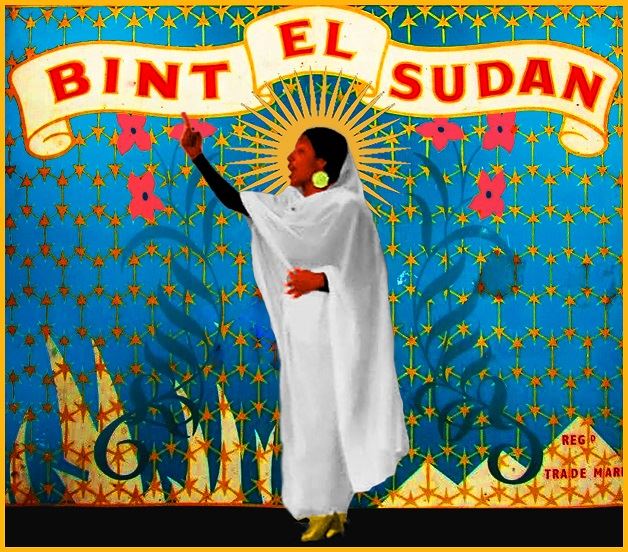

Image of Bint El Sudan perfume label remixed to show the iconic image of 22-year-old Alaa Salah, a protester who brought global attention to Sudan’s revolution. Image by artist Amado Alfadni, used with permission.

Sudan’s uprising has been in the works for months now, but the iconic image of 22-year-old Alaa Salah chanting poems and slogans of resistance while standing on top of a car in Khartoum, the capital, went viral, bringing global attention to the revolution. Salah has been likened to Sudan’s Statue of Liberty, the nation’s Nubian Queen.

The original photo of Salah, taken by Sudanese student, Lana Haroun, has inspired artists around the world to exalt Salah as a symbol of the revolution. Artist Amado Alfadni, born and raised in Cairo, Egypt, with Sudanese roots, seized the opportunity to remix the image with the classic “Bint El Sudan” or “Daughter of Sudan” perfume label.

Created in the 1920s by WJ Bush in London, the best-selling perfume has been dubbed Africa’s “Chanel No. 5″ and is worn widely by women throughout Sudan and East Africa. The ubiquitous non-alcoholic scent — a musky mix of jasmine, lilac and lily — was first sold not in exclusive shops but public markets, eventually becoming an essential part of weddings and circumcision rituals as a staple in Sudanese women’s lives. The scent triggers notions of feminity, power and allure. It’s also recognized as having magical and medicinal qualities that stem from Sudan’s ancient aromatic and herbal traditions.

Alfadni explains: “Bint El Sudan was my mother’s perfume and so [it] was a part of the identity I made for myself as a Sudanese person.”

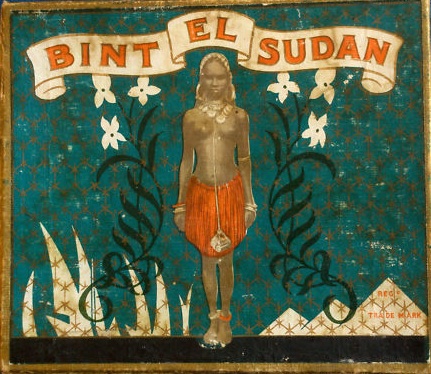

Original Bint El Sudan perfume label features a photo credited to Eric Burgess, who first brought the idea of creating a perfume to his London-based company WJ Bush & Co. in the 1920s. Photo shared by artist Amado Alfadni, used with his permission.

The original perfume label featured a photograph of a topless young Sudanese woman wearing a traditional Sudanese elephant-hair skirt and adorned with bridal jewelry on her ankles and wrists. It was taken by Eric Burgess, a representative for WJ Bush’s business interests in Sudan.

For decades, the image of this young woman traveled from Khartoum, Sudan, to Kano, Nigeria, as traders reportedly began using the heady scent as a form of currency.

Twenty years ago, Alfadni says, Sudan’s Islamic regime changed the original image of the topless girl to one wrapped in a modest black burqa in alignment with Islamic values.

Omar al-Bashir ruled Sudan for 30 years (1989-2019) and introduced penal code reforms — based on strict interpretations of Sharia (Islamic Law) — in 1991. Bashir’s reforms relegated women to the status of legal minors and restricted their freedom of movement by enforcing strict “morality laws” and gender segregation in public spaces. Women have faced flogging and death by stoning for violating these laws.

The modest Bint El Sudan perfume bottles were introduced 20 years ago under strict interpretations of Islamic law. Photo by Amado Alfadni, used with his permission.

“What she wears — that is actually what women used to dress like in my home town in northern Sudan,” Alfadni said in an interview via Facebook messenger. “The same with Nubians of Egypt, I am also Nubian,” he wrote.

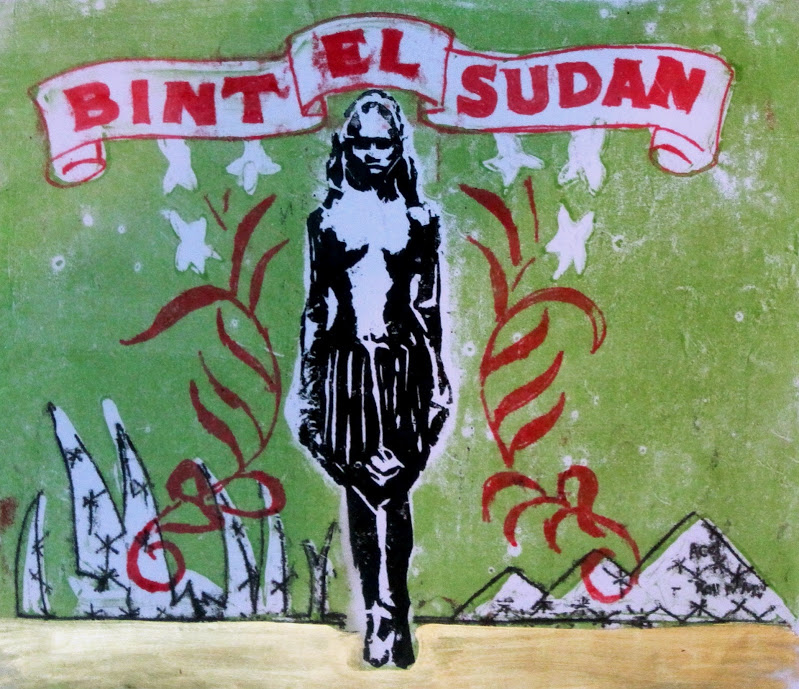

Not much has changed about Bint El Sudan’s unique formula in 100 years, but the clothing of the young woman on the label has been modified over time to reflect enduring debates about women’s modesty.

Bush Boake Allen, the company that produced various Bint El Sudan products beginning in 1966, re-imagined the label with a young woman who resembles the original traditional Sudanese bride but draped in red to cover her chest — a slight modification to accommodate more modest markets, depending on where the Bint El Sudan products were sold.

Bint El Sudan moisturizer features the young Sudanese woman but in this version, her chest is covered by a red cloth. Photo via Instagram by genaropiano.

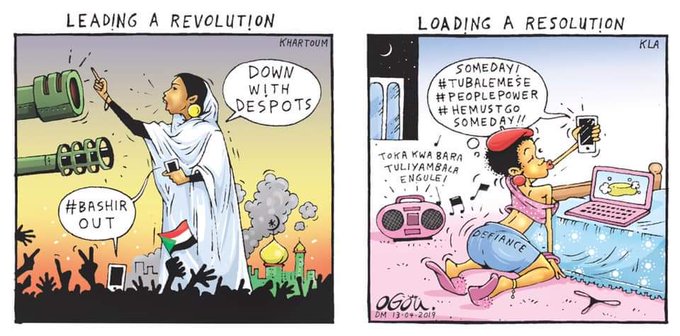

Women have been on the frontlines of protests that kicked off in December 2018 over the price of bread and spiraled into full-scale demonstrations confronting women’s oppression in public and private spaces, among other grievances.

Eventually, protesters called for the resignation of Bashir — who is also wanted for the role he played in numerous alleged crimes against humanity.

On April 11, after protesters surrounded security headquarters in Khartoum, Bashir was arrested by the military in what has been described as a military coup — that only lasted one day. General Ibn Auf, Sudan’s defense minister, called for a three-month state of emergency and two-year transitional government led by the military but stepped down as the transitional leader as protesters insisted on civilian-led leadership.

Ironically, the spicy, sweet scent of Bint El Sudan is now produced in a small factory in Kano, northern Nigeria, — a region terrorized by Boko Haram, a militant group aligned with ISIS. The tightly-secured factory produces approximately seven million 12-milliliter bottles per year, at least 80 percent of the world’s demand.

While Alaa Salah’s image has brought global attention to Sudan’s struggle for regime change — and inspiring artists like Alfadni and others to exalt her as a symbol of the revolution — feminists and activists have warned against the dangers of any single person carrying the burden of revolution, noting that many unnamed women have come before her and that Salah herself has received death threats.

As for Alfadni, he said his decision to remix the famous perfume label with Salah’s image was about challenging notions of Sudanese identity: “I am trying to represent the image of Sudan away from anger and extremism.”

A print of the Bint El Sudan perfume label by the artist Amado Alfadni, 2011, photo by the artist and used with his permission. This is part of Alfadni’s project exploring the history and significance of Bint El Sudan as both a perfume and part of Sudanese culture and history.

Source: The scent of revolution: The story behind Sudan’s legendary perfume label remix · Global Voices