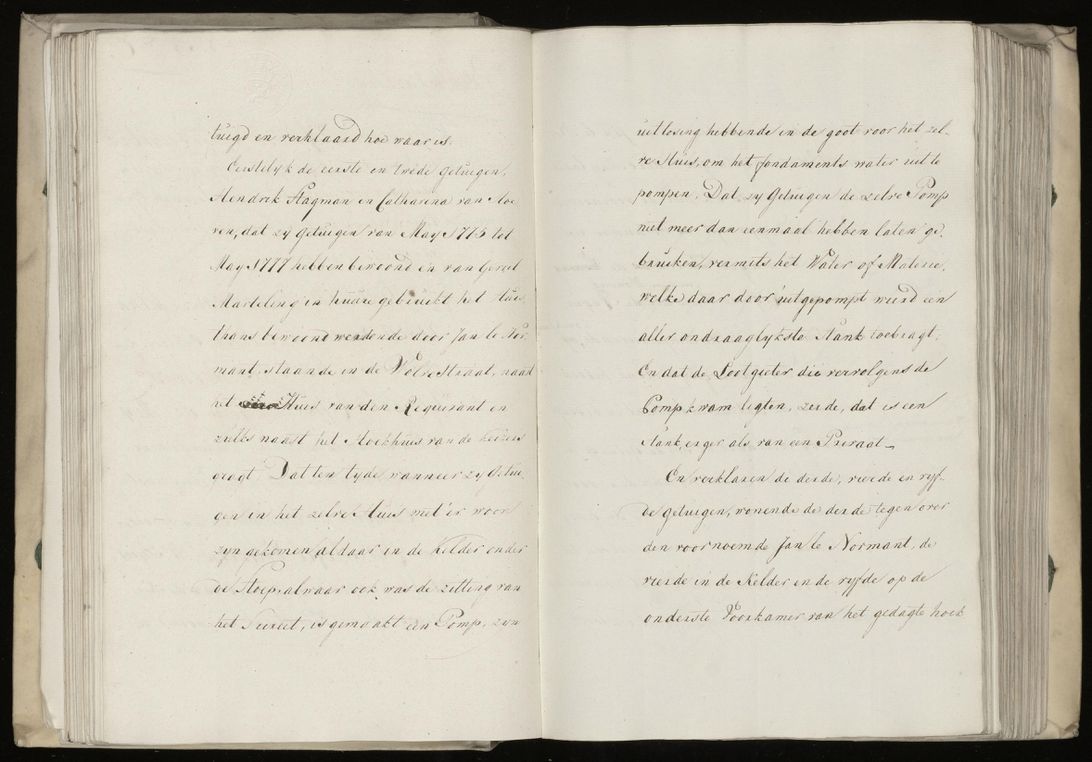

“On the Evening of the Battle of Waterloo,” by British painter Ernest Crofts, shows Napoleon leaving the battlefield after the defeat of his army in 1815. The Odeuropa project aims to enhance the understand of historical events like this one by re-creating the smells that defined it. Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

As part of a project called Odeuropa, researchers from six countries are bringing historical European smells, including the Battle of Waterloo, to modern noses. “Smells shape our experience of the world.”

Many paintings and books have illustrated the Battle of Waterloo, but what, exactly, did it smell like as an anxious Napoleon Bonaparte and his army retreated? An international team of researchers hopes to archive the olfactory experience of that pivotal historical moment as part of an ambitious new initiative to discover key scents of old Europe, from the perfumed to the putrid, and bring them to modern-day nostrils.

Odeuropa‘s goal is “to show that critically engaging our sense of smell and our scent heritage is an important and viable means for connecting and promoting Europe’s tangible and intangible cultural heritage,” according to a description of the project, which just received a $2.8 million euro ($3.3 million) grant from a research and innovation arm of the European Union.

If it’s hard to imagine the smell of a defeated Napoleon fleeing on that history-making day in 1815, think the scent of rain-soaked soil and grass mingling with the fetid odor of rotting corpses and earth burned by explosions, as described in soldiers’ diaries. Mix in leather and horses, gunpowder and even the smell of the French emperor himself.

“We know Napoleon was wearing his favorite perfume that day, which would resemble the present-day 4711 eau de cologne and which was called ‘aqua mirabilis,'” says Dutch art and scent historian Caro Verbeek, an Odeuropa team member. Her dissertation traced the scents of the Battle of Waterloo, and will serve as a foundation for Odeuropa’s work to reconstruct it.

Napoleon chose his fragrance to mask the evil stench of battle, Verbeek says, but also to stay healthy, as the cologne contained compounds believed at the time to help protect people from disease.

“This perfume was used in almost every war since by many soldiers and for the same reasons,” the researcher adds.

Verbeek joins a multidisciplinary team from six countries in fields ranging from sensory, art and heritage history to computer science, digital humanities, language technology, semantics and perfumery. As one part of Odeuropa, they plan to curate and publish an online encyclopedia that details historical European smells from the 16th to the early 20th centuries.

“Smells shape our experience of the world, yet we have very little sensory information about the past,” says the project’s lead, Inger Leemans.

But for the history-obsessed, the most exciting outgrowth of the three-year project will likely be the reconstructed smells. The Odeuropa team plans to work with museums, artists and chemists to re-create not only aromas, but as much of the sensory experience that surrounded them as possible. They will then curate olfactory events that take participants on sensory trips back in time.

“One can really learn by smelling,” says Leemans, a professor of cultural history at Amsterdam’s VU University and the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences Humanities Cluster.

One goal of Odeuropa, Leemans says, is to give modern-day Europeans a visceral experience of what their forebears inhaled during key historical turning points like the industrialization era. “One can learn about coal, mines, textile industries and proletarization by reading or watching clips,” Leemans says, “but imagine what would happen if you confront the public with the olfactory shift between a rural and an industrial environment.”

The smell sleuths will scour thousands of images and texts, including medical textbooks and magazines found in archives, libraries and museums, using AI trained to spot scent references and iconography.

“Our work with AI will also inform us about the frequency with which the smells were mentioned in certain historic periods, and the feelings associated with them,” says Cecilia Bembibre, a heritage scientist with University College London’s Institute for Sustainable Heritage who previously helped create a system to identify and catalog the smells of old books. These findings will help the team decide which smells have enough cultural value to be included in the project.

The online scent archive, accessible to the public, will describe the sensory qualities and stories of various scents. It will share the history of olfactory practices, investigate the relationship between scent and identity, and explore how societies coped with challenging or dangerous odors.

The hope is that such a resource could help museums and educators enrich the public’s knowledge of the past. While a select few museums have included smell for a more multisensory experience, most mainly rely on visual communication.

If scents could speak

Anyone who’s smelled a bonfire and immediately been transported to a high school beach party or sniffed a grandma’s scarf and been filled with longing knows that smell plays a powerful role in memory and emotion. It stands to reason, then, that engaging with smells of the past could allow us to interact with history in a more emotional, less detached way.

University College London heritage scientist Matija Strlič says one challenge facing the Odeuropa researchers will be making sure they accurately capture not only the chemical compounds that make up a particular aroma, but its cultural context.

“We have some understanding of what smells used to be popular in the past,” he says, “but it is difficult to imagine the differences in their perception, even if generally pleasant, today and a hundred years ago, given that our society has come to associate cleanliness with the absence of smell.”

For an example of a smell with vastly different cultural implications then and now, look to simple rosemary. When a plague outbreak ravaged 17th century London, so many people included the herb in a mixture to purify the infected air that its distinct aroma filled the streets, becoming inextricably associated with disease.

Take another everyday smell, tobacco, which is smoky, pungent and redolent with historical and sociological insights.

“It links to histories of sociability, of trade and colonization and also health,” says William Tullet, a smell historian from England’s Anglia Ruskin University and a member of the Odeuropa team.

The project launches amid a heightened global awareness of smell’s power. Evidence links a loss of smell to COVID-19, with patients who’ve gotten the virus describing in vivid detail how it feels to suddenly find themselves without a sense they once took for granted. The increase in COVID-19 patients reporting a temporary loss of smell is so significant that in some countries, such as France, people who experience sudden olfactory loss are diagnosed as having COVID-19 without even being tested.

Odeuropa’s scope is unprecedented, but the project doesn’t mark the first attempt to engage noses in the name of safeguarding heritage. The Jorvik Viking Centre in York, England, re-creates 10th century smells for visitors, and even offers aroma packs so history buffs can bring home Viking smells from candle wax to rotting meat. “You can re-create the ambience of a Viking forest, street trader or even a cesspit in whatever space you want — from a classroom to a domestic WC,” the organization says.

Some would argue that there are smells, like those of battle, best left to the annals of history. The Odeuropa team believes in inhaling the whole bygone bouquet, even the rancid parts.

Source: The past stunk. Scientists want you to be able to smell it