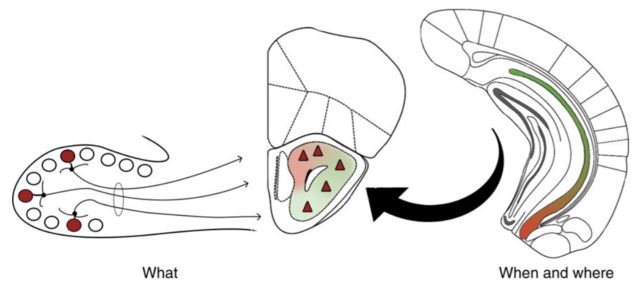

Conceptual diagram for the formation of episodic odour memory. A model of episodic odour memory whereby information regarding odour quality and spatiotemporal context merge at the level of the anterior olfactory nucleus (AON) producing cellular populations that represent previously encountered odours (what) within the context in which they occurred (when and where).

Source: Afif J. Aqrabawi & Junchul Kim (2018) Nature Communications/Creative Commons

Can you recall a specific odor or scent that has the ‘spatiotemporal‘ ability to transport you back in time and space to a very specific place from your past? Most of us have experienced how the unexpected whiff of a Proustian, Remembrance of Things Past, type of odor can instantly evoke flashbacks to somewhere long ago or far away. Until recently, the underlying brain mechanisms that encode these vivid time-and-place smell memories has been a mystery. But now, for the first time, a new study, “Hippocampal Projections to the Anterior Olfactory Nucleus Differentially Convey Spatiotemporal Information During Episodic Odour Memory,” helps to explain how ‘what-when-and-where’ smell memories are stored in the brain. This paper was published July 16 in the journal Nature Communications.

For this pioneering olfactory research, neurobiologists at the University of Toronto created an animal model using mice to pinpoint the neural correlates that link sensory-rich memories to a specific time and place associated with a distinct odor. The findings of this research advance a neuroscience-based explanation as to why losing smell-based memory associations is an early symptom of Alzheimer’s disease in humans.

“Our findings demonstrate for the first time how smells we’ve encountered in our lives are recreated in memory. In other words, we’ve discovered how you are able to remember the smell of your grandma’s apple pie when walking into her kitchen,” first author Afif Aqrabawi, a Ph.D. candidate in the University of Toronto’s Department of Cell and Systems Biology said in a statement. “When these elements combine, a what-when-where memory is formed.”

Agrabawi conducted this research with graduate supervisor Professor Junchul Kim from the U of T Department of Psychology who oversees The Kim Lab.

What makes this research potentially groundbreaking is that Aqrabawi and Kim have unearthed specific ways that a poorly understood region of the brain called the “anterior olfactory nucleus” forms neural pathways with the hippocampus. These odor engrams integrate the exact place and time a particular smell was woven into a unique neural tapestry that holds distinctive what-when-and-where smell memories.

The authors explain: “Our findings reveal a previously unreported function for the AON, a structure that has long remained elusive in its role in olfactory information processing. The AON, in its position immediately posterior to the olfactory bulb and anterior to the piriform cortex, maintains connections at nearly every synaptic step in the olfactory pathway. Its central arrangement and extensive command over activity within the olfactory cortex makes the structure a conceivable repository of episodic odor engrams.”

“We now understand which circuits in the brain govern the episodic memory for smell. The circuit can now be used as a model to study fundamental aspects of human episodic memory and the odor memory deficits seen in neurodegenerative conditions,” Aqrabawi said.

The researchers are optimistic that their recent findings on the link between hippocampal projections to the AON and spatiotemporal smell memories will lead to more effective ways to examine these neural circuits in humans. “Given the early degeneration of the AON in Alzheimer’s disease, our study suggests that the odor deficits experienced by patients involve difficulties remembering the ‘when’ and ‘where’ odors were encountered,” Kim concluded.

Brick-and-Mortar Stores Through the Lens of What-When-and-Where Smell Memories in an Era of Odor-Free Online Shopping

My grandparents were part of the Woolworth’s generation during the peak of “five-and-dime store” popularity. As a young couple in the early- to mid-20th century, they spent a lot of time during their formative years at the five and dime either shopping or socializing over lunch at the Woolworth counter.

In the 1970s, when I was growing up, the synthetic and kind of musty smell of any Woolworth store was etched into my memory banks as something very commonplace yet out-of-date. The ‘Woolworth’s smell’ always reminded me of gramma and grampa. Nevertheless, I created my own what-when-and-where smell memories in Woolworth’s when I was younger.

As a pop-music-loving kid in the ’70s, I’d listen to “Casey Kasem’s American Top 40 Countdown” on the radio every weekend. Then, I’d nag mom to drive our Chevy station wagon to Woolworth’s so I could scavenge through the record bins and purchase one or two vinyl “45s” with my weekly allowance.

To this day, I can clearly remember buying the single for “Mamma Mia” by ABBA along with “Nights on Broadway” by the Bee Gees and a pack of newly-invented Bubble Yum, which was a hot commodity in 1975 when I was nine. The smell of bubblegum never fails to take me back to this specific time and place.

Woolworth’s went out of business almost two decades ago (July of 1997) and has been a source of nostalgia for me ever since. It was sentimental to hear a cover version of “Mamma Mia” again while watching the ABBA-inspired Meryl Streep sequel (with a Cher cameo) recently. For me, a lot of the 1970s songs from this 2018 movie musical brought back vivid memories of being in Woolworth’s over 40 years ago. Because “the world’s greatest five-and-dime store” went bankrupt decades ago, I realize that my 10-year-old daughter will never smell the very distinctive Woolworth’s odor that was etched into the AON neural pathways of previous 20th-century generations.

Since the millennium, countless brick-and-mortar stores have shuttered their doors. The odor-free online experience of visiting Amazon, Netflix, Spotify, iTunes, Kindle, Grubhub, and Carvana (to name a few) has replaced the enriched olfactory experience of going to the shopping mall, movie theaters, Blockbuster Video, Tower Records, vintage bookstores, neighborhood restaurants, automobile showrooms, etc. Visiting these brick-and-mortar shopping locations inherently created scent-based engrams linked to a specific time and place that older generations can still reminisce about decades later.

What impact will the lack of smell memories associated with specific time and place in our day-to-day lives driven by odor-free internet experiences have on our hippocampal projections to the anterior olfactory nucleus and long-term memories?

With more and more time spent socializing via the internet and shopping online, we are being exposed to fewer novel scents in different locations. Inevitably, with less and less time spent mingling in public spaces or frequenting brick-and-mortar stores, the parts of our olfactory system that encode what-when-and-where odor memories aren’t being enriched with as much olfactory and spatiotemporal stimulus as in yesteryear.

From an evolutionary standpoint, I wonder what long-term impact the scent-free experience of “one-click” shopping and streaming media content directly into a personal device will have on the collective olfactory memories of my daughter’s generation. Luckily, my daughter and her friends were able to see Mamma Mia! Here We Go Again on a big screen in a packed theater. Surely, this movie-going experience encoded lots of what-when-and-where odor memories.

For anyone who is too young to have visited a Woolworth’s before they went out of business—or is old enough to recall that very funky Woolworth’s smell—Nanci Griffith humorously describes this distinct odor in a live performance of her song, “Love at the Five and Dime” from the One Fair Summer Evening (1988) DVD.

As she introduces the song in the video above, Griffith says, “Woolworth stores are the same all over the world. They have this wonderful smell to them. They smell like popcorn and chewing gum rubbed around on the bottom of a leather-soled shoe.” Nanci Griffith also describes intimate spatiotemporal details of her hometown Woolworth’s at Sixth and Congress in Austin, Texas juxtaposed to her first trip to Europe where she was awe-struck by a massive Woolworth’s in Central London as an older adult in the 1980s. Her detailed “what-when-and-where” storytelling takes on some neuroscience-based significance in light of the latest findings by Aqrabawi & Kim.

Using What-When-and-Where Odors to Go “In Search of Lost Time”

In recent decades, the classic olfactory-driven novel by Marcel Proust (1871–1922) about the protagonist Swann having involuntary flashbacks to his youth after smelling a madeleine dipped in tea is commonly referred to as In Search of Lost Time. According to experts, this English translation of the original French title, À la recherche du temps perdu, is more accurate than the previous translation “Remembrance of Things Past.”

A few weeks ago, I made a nostalgic trip back to my family’s old farmhouse in Western Massachusetts to celebrate the Fourth of July. During this visit, I found a long-forgotten wooden box full of various smells from my adolescence stashed away in the attic. Since then, the smells held in this box have proven to be a treasure trove in terms of triggering an urgent midlife need to go ‘In Search of Lost Time’ from my youth. Over the past month, these various spatiotemporal-linked odors have helped me kickstart a fresh outlook and seize-the-day attitude in a timescape marked by crippling anxiety and uncertainty.

Later this week, in a follow-up blog post, I’ll share some road-tested insights on how to use odors from your past that are encoded with specific ‘what-when-and-where’ memories to promote a growth mindset and openness to new experience. (For for more see, “Using the Power of Smell to Step Outside Your Comfort Zones“)

In the meantime, hopefully, learning how the brain encodes smell memories linked to a specific time and place will inspire you to keep your nose out for odors you encounter in daily life that may hold the power to remind you of exactly where and what you were doing in the summer of 2018 decades from now.

References

Afif J. Aqrabawi & Junchul Kim. “Hippocampal projections to the anterior olfactory nucleus differentially convey spatiotemporal information during episodic odour memory.” Nature Communications (Published: July 16, 2018) DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-05131-6

Source: The Neuroscience of Smell Memories Linked to Place and Time | Psychology Today