In 2015, artist Ani Liu heard two sentences that changed her entire approach to art: “Digital is dead. Bio is the new digital.” Those words, spoken at a welcome talk on her first day as a grad student at the MIT Media Lab, triggered panic at first. “I was like, oh shit, I don’t know anything about biology,” Liu says.

But today, biology is the starting point for most of Liu’s work. Her feminist artworks are visceral, thought-provoking, and anchored in biotechnology. “I like to say that I have a research-based practice,” Liu says. “Each of the artworks I make are usually centered around a specific topic that I do a deep dive of research into.”

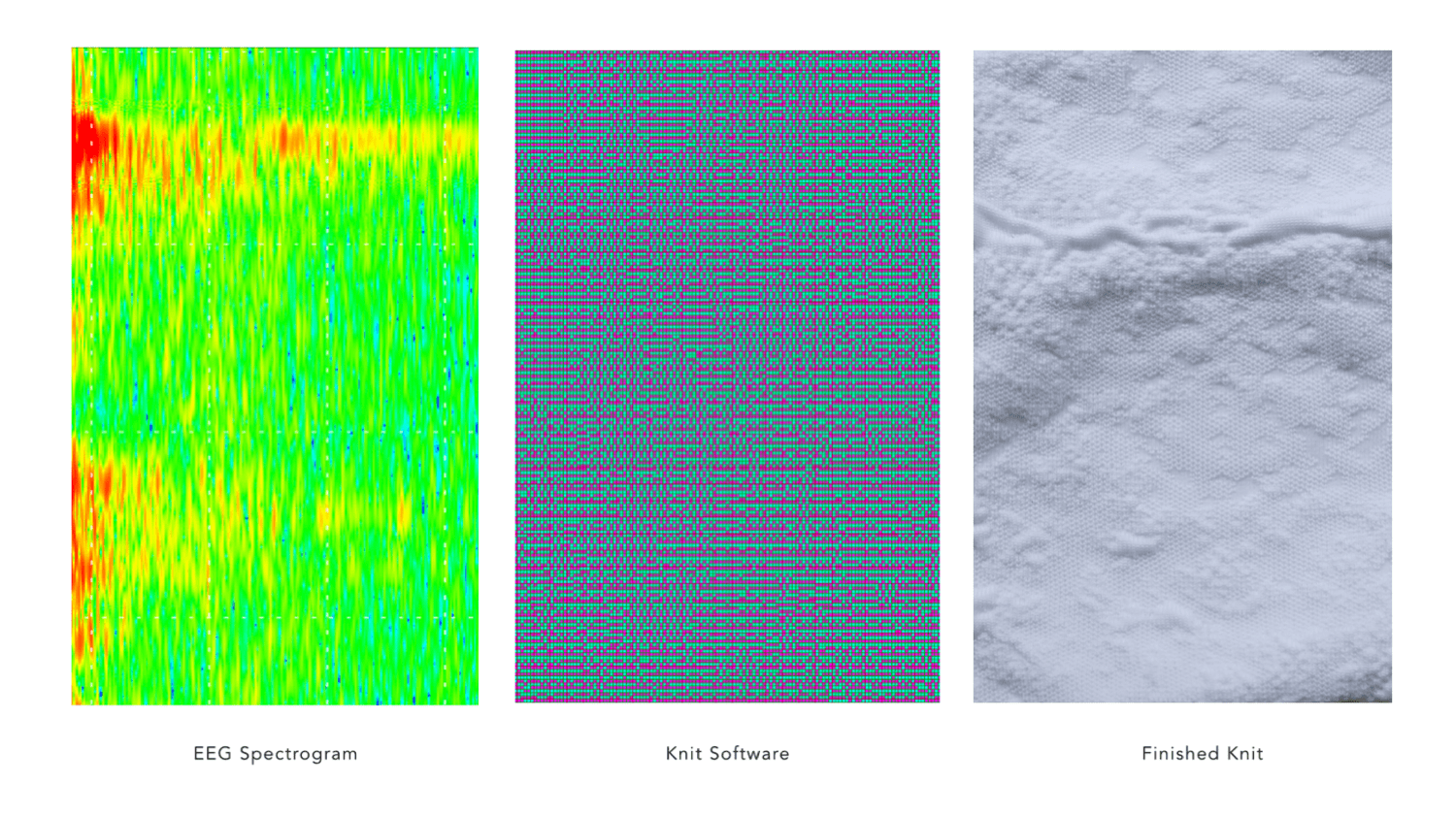

Her body of work is executed through experimentation: She’s used organic chemistry to concoct perfumes that smell like people emotionally close to her; she’s programmed a knitting machine to produce a a garment worker’s brain signals; she’s engineered a device that enables the wearer to control the direction of swimming sperm with their mind.

The throughline of her work is speculative design, an approach to art and design that critiques larger societal issues. Speculative design isn’t about predicting the future, Liu clarifies. “It’s different ways of considering the future, and hopefully, they’re actionable. But for me, it’s the importance of letting things outside of capitalism drive progress.”

Her pieces provide a moment to pause. “One of the things that I find so important about speculative design is that it allows people to reflect on the implications of the technologies that we consume, instead of kind of blindly going along with it,” Liu says. “I feel like it forces us to unpack what is going on.”

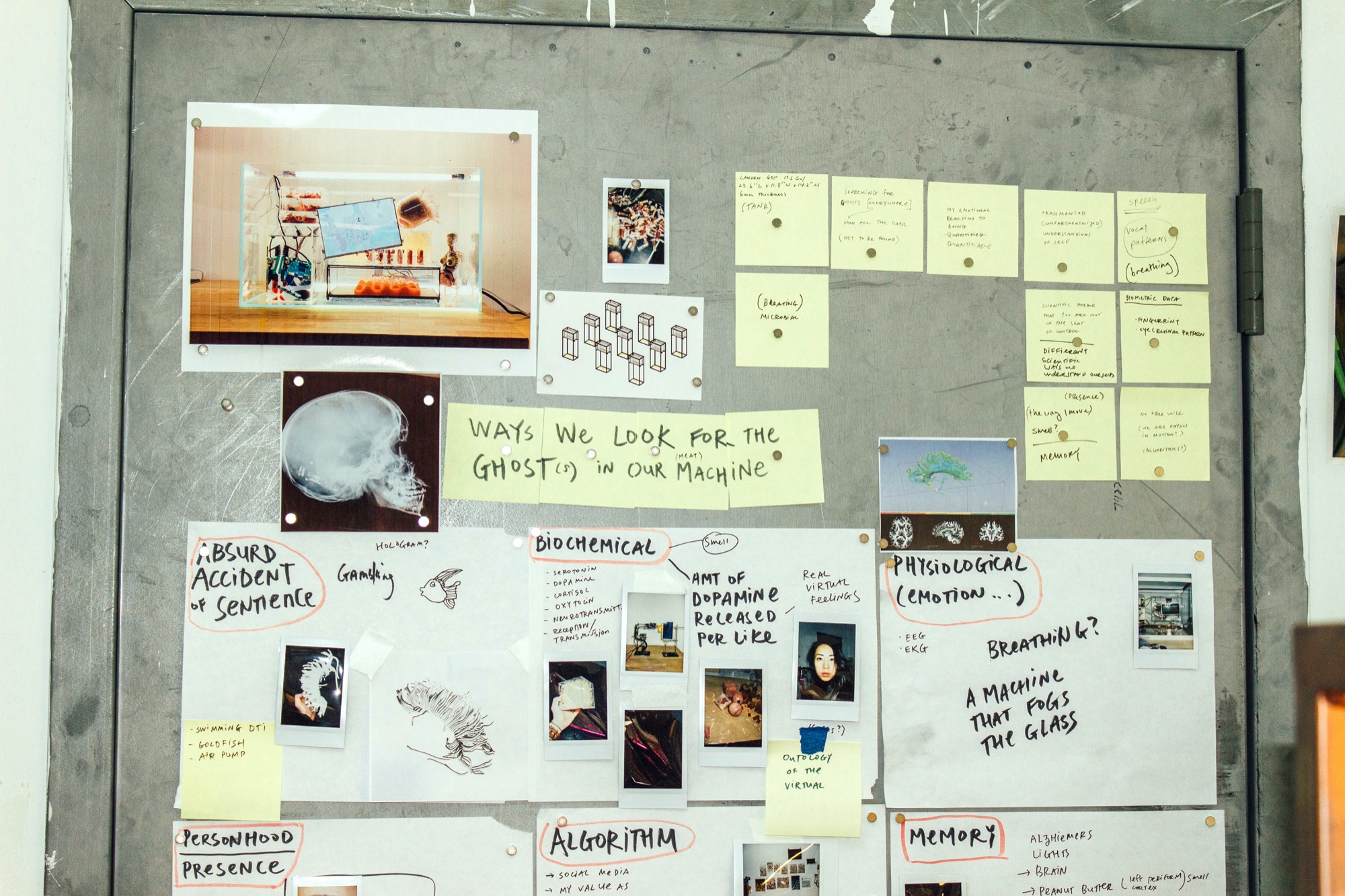

Liu’s workspace in Long Island City, New York has more in common with a scientific lab than it does a traditional art studio. Jars of organic matter, electrodes, and machines are strewn across her desk and shelves. Tucked in one corner, a tank filled with circuits and electrodes sits leftover from her “Real Virtual Feelings“ project.

Liu points to a two-foot-tall clear tube of stringy, sinew suspended in a pus-like liquid. She wanted to create an iteration of a self-portrait, based on the materials in her body. She even worked with a radiologist who helped her take scans of her body to figure out the percentages of water, fats, and different kinds of proteins, “to try to show a portrait of myself as a kind of stratified tube of goop,” she explains. But, she found the organic soup wasn’t very stable. “Some of the prototypes I would make would start to [let] off gas, they weren’t sterile. Sometimes they would explode,” she laughs.

Like the explosive mixture of those early prototypes, Liu didn’t mix well with science and math at first. “At some point early on, an authority figure told me that girls are bad at math,” she says. “And it really sunk deep into me. For most of my life, I felt so intimidated by laboratories and science and technology.”

That changed when she decided to approach art with materials that required math, science, and technology. “I was like, oh, I’m not that bad at circuit making, or this isn’t actually outside my realm of possibility. It wasn’t until I used it as a secondary tool that it really felt natural.”

Read full article by clicking source link below: