Gilberto Esparza, Plantas autofotosinthéticas [Autophotosynthetic Plants] (2013–14) (detail). Polycarbonate, silicon, stainless steel, graphite, electronic circuits, local wastewater, natural pond water with micro algae and microorganisms, plants, shrimp, fish, sound. 400 × 400 cm overall. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Axel Heise.

Anicka Yi, Pierre Huyghe, and Jenna Sutela are among the artists interrogating our relationships with non-humans at the university’s List Visual Arts Center.

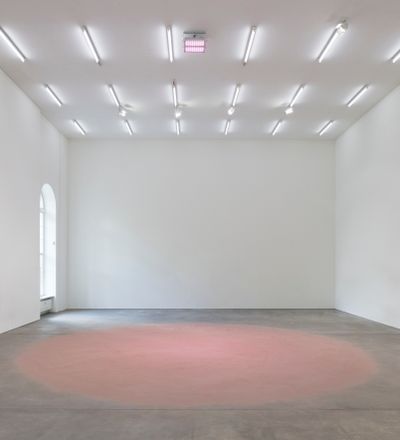

A wide circle of pink sand is scattered on the floor in Pamela Rosenkranz‘s installation She Has No Mouth (2017). Loosely resembling kitty litter, the work alludes to the toxoplasma parasite commonly found in feline faeces. Making its way into mice, toxoplasma alters their neural pathways to prevent them fleeing cats, thereby enabling the cats to catch their prey and the parasite to return to its preferred host.

The ingredient is so effective that the perfume has been used to draw jaguars to camera traps and capture man-eating tigers. Just as animal behaviour can be manipulated by a man-made scent, our behaviour may be altered by toxoplasma in ways we don’t yet fully understand. An estimated 30 to 50% of humans carry the parasite.

Interspecies relationships like this are the subject of the exhibition Symbionts: Contemporary Artists and the Biosphere, which takes place at MIT’s List Visual Arts Center from 21 October 2022 to 26 February 2023.

In particular, the exhibition focuses on ways contemporary artists position human beings in relation to other species and entities. Rosenkranz, for example, spritzes the pink sand of her installation with Calvin Klein’s Obsession For Men. The cologne contains a synthetic version of civetone, a pheromone produced by the African civet.

Symbionts is curated by MIT professor Caroline A. Jones and List curators Natalie Bell and Selby Nimrod.

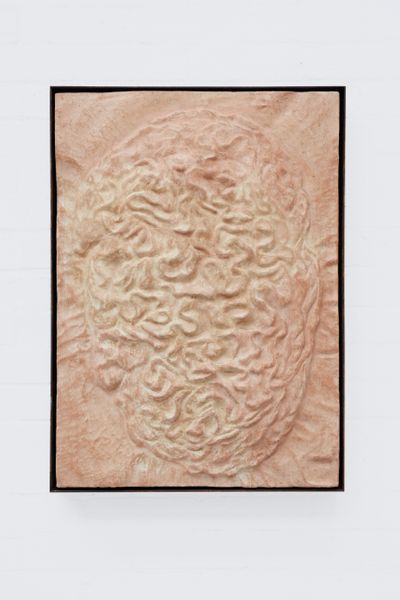

It features new works including Gut Flora (2022) by Finland’s Jenna Sutela, a former visiting artist at MIT’s Center for Art, Science & Technology (CAST). Sutela made tiles of clay containing mammalian dung, which she fired and then glazed with breast milk. They feature bas-relief images modelled on flowers sent to Sutela when she was recovering from childbirth.

The work is ‘a kind of circuitry with the maternal body as a factory generating a baby that poops and breast milk that comes from evolutionary sweat glands,’ Jones said.

Breast milk passes healthy microbes from mother to child, while dung alludes to the emerging practice of faecal transplants for people whose microbiome is languishing in some way, impairing their ability to absorb nutrients, weakening their immune system, or exacerbating anxiety and depression.

Nour Mobarak employs human matter too, using hair and sperm in her work Reproductive Logistics (2020–21), a colour-coded chart of the artist’s exes overcome by a brown crust of mycelium. The mycelium comes from a fungus that can shift between sexual reproduction and self-reproduction in response to environmental adversities, a model of independence.

Live cellar spiders will be released in the gallery in a work by Pierre Huyghe that upends the expectation of a sterile white cube, but there’s a contribution the curators anticipate being even more difficult to install and maintain.

Gilberto Esparza’s Autophotosynthentic Plants (2013–2014) is a room-sized installation built around a central goldfish bowl-type ‘nucleus’ that holds pond water, protozoa, plants, small fish, and shrimp. Surrounding this glass orb are 12 six-foot-tall towers containing microbial fuel cells, which use bacteria and wastewater to generate electricity that is transformed into bursts of light the plants can use for photosynthesis in the darkness of the gallery.

‘We’re in the process of working with wastewater services to source 12 different samples of greater Boston area wastewater,’ Bell said. Looking at the lights, visitors will be able to see varying levels of activity, and thereby infer which areas are most polluted.

The work ‘actualises a potential for bioremediation,’ Bell said.

The exhibition’s curators emphasise that symbiotic relationships are not always mutually beneficial. They can also be parasitic, where one species benefits to the other’s detriment, or commensal, where one benefits and the other is largely unaffected. During what has been described as Earth’s sixth mass extinction, most species are not benefiting from human activity.

One artist who touches on extinction is Miriam Simun, who will premiere a new video installation called Interspecies Robot Sex (2022). The film examines two solutions to the collapse of honey bee colonies, which play a crucial role in pollinating plants. Hand pollination has been carried out in apple and pear orchards in China’s Anhui province since the 1980s, while Harvard’s RoboBee project explores whether the job can be done by tiny drones.

Audio for the work includes speakers embedded in the seating, vibrating as if with a bee hive’s buzzing, but no actual bees appear on screen.

‘That’s the closest thing to a kind of grief in the show, noting the bees’ absence through that body-vibration,’ Nimrod said.

A site-specific installation including beeswax mixed with lemongrass oil, a scent used to attract bees, and Massachusetts blossoms, adds another olfactory element to the exhibition.

While some artists use scents very deliberately in the MIT exhibition, Nimrod emphasises that all art materials have a smell.

‘I really want to normalise people smelling art,’ she said.

From lemongrass oil and wastewater to mycelium and civetone, the use of non-traditional materials is a key strategy in these artists’ reminders that as animals we juggle relationships with countless non-human entities.

In these works, Jones points out, ‘a lot of the narrative is cleverly conducted in the object labels.’ —[O]

Source: Spiders, Sperm, and Calvin Klein Obsession Co-exist in MIT Show ‘Symbionts’ | Ocula News