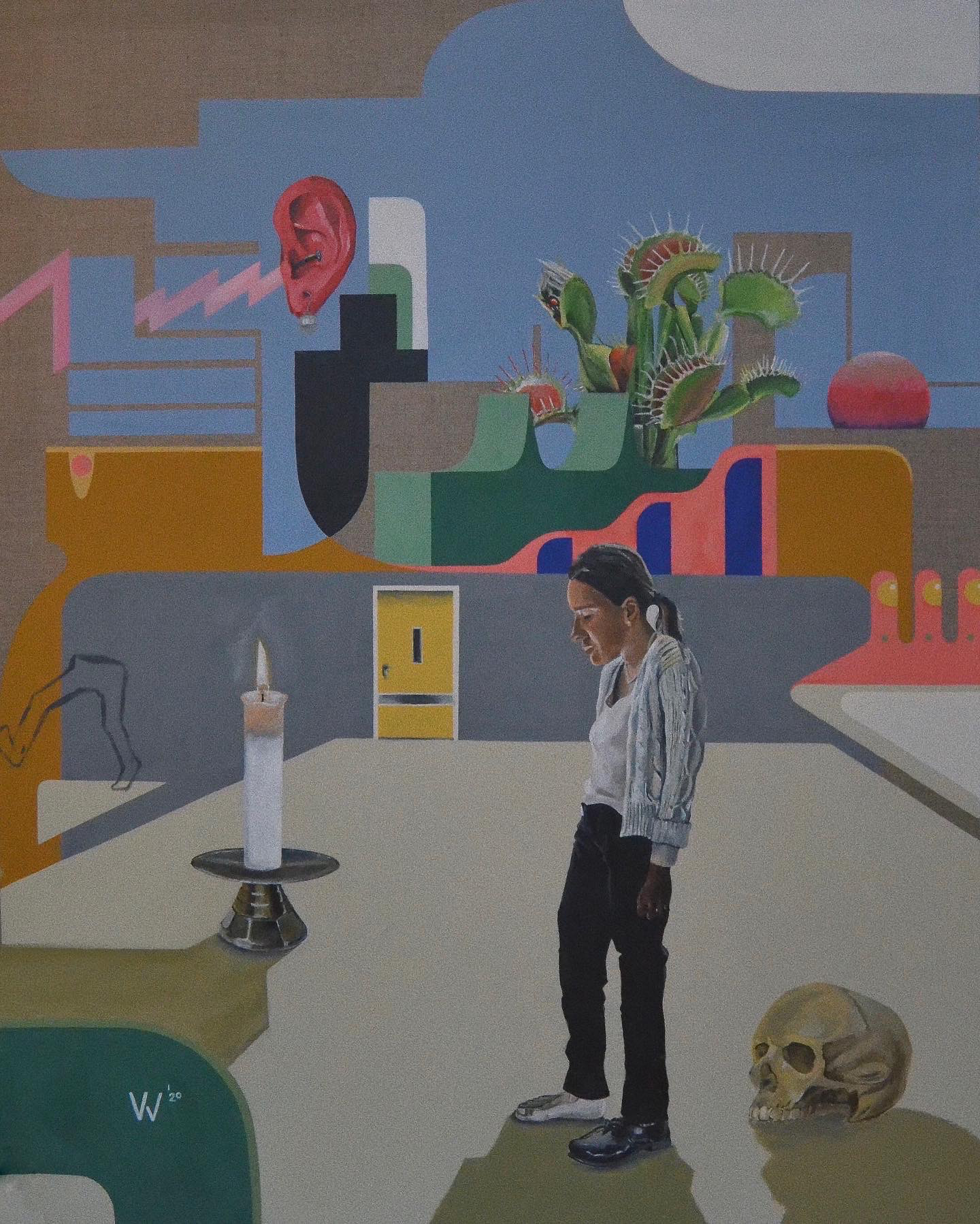

Virgilio Vogels, Desert Room. Digital painting, print. Vogels depicts the situation of a patient diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia in a psychiatric clinic. Image credit: Virgilio Vogels

EDGE’s recent neuroscience–art exhibition is a place for the “neurocurious” where science and art fuse to create something more than just art about science.

I’m sitting on a chair looking at an abstract painting of swirling mustards, muds and maroons, but so far, I can’t make much sense of it. The artist, Roxana Ardeleanu, then puts a pair of headphones over my ears and I listen to the whirring and chattering of the soundscape. Slowly, the painting begins to change: a face begins to emerge out of the fog with cobalt eyes. It is as if it has always existed – das ding an sich – but the soundscape has lured the face from the paint and into my consciousness.

Roxana Ardeleanu. Sens(e)scape. Acrylic paint on canvas with accompanying audio. This piece invites the viewer to exchange the identities of sound and color, for the perception of both to become one in a sensorial symbiosis.

Ardeleanu’s piece, titled Sens(e)scape, is an exploration of her experiences with synesthesia; it challenges you to question the idea that different sensory modalities, in this case vision and sound, are so distinct. “I only found out I have synesthesia a couple of years ago. Because my synesthesia is usually link sound to color, this piece was a reversed experiment where I wanted to experiment translating my visual experience of the painting into an auditory one.” says Ardeleanu.

The way Sens(e)scape causes my perception to blend and shift reminds me of visual illusions like the duck–rabbit illusion. They both involve a constant visual stimulus, but invoke a switch between perspectives that is dependent on cognitive processing factors in the brain. In the case of Sens(e)scape, that factor seems to be the simultaneous processing of sound and vision, where one influences the perception of the other. Ardeleanu’s piece now has me questioning how sound shapes vision and vision shapes sound.

Roxana Ardeleanu. Sens(e)scape. Closeup image. Image credit: Roxana Ardeleanu.

Roxana Ardeleanu. Sens(e)scape. Closeup image. Image credit: Roxana Ardeleanu.

Neuro–art, not art about neuroscience

This is what this exhibition, curated by EDGE, is all about; how neuroscience and art interact to push the boundaries of our understanding of the brain and the mind. At first glance, art and neuroscience seem like an uncomfortable fit. They may ask the same grand questions – how do we experience the world around us? What is the nature of emotion and consciousness? But their methods and output are completely different, right?

No, says EDGE co-founder Ian Stewart rather vehemently. “The more we’ve been running EDGE, the more we’ve realized that not only is it an artificial divide between science and art, but also that it’s also damaging to keep perpetuating that idea. There’s a lot to be gained by allowing these two fields to come together.”

Ardeleanu agrees, “Art is a useful tool to use to research about the mind and the brain, where the process of exploration is more important than the product or methodology. All art is in some form research about the mind and perception, using subjectivity as a tool. This is opposed to science which explores these themes empirically.”

Challenging the idea that there is an ideological divide between artists and scientists is one of the central missions of EDGE. Through their monthly workshops and annual exhibitions, they aim to bring art and neuroscience collaborations into the public sphere. EDGE’s most recent exhibition, their third, was held in the MIND institute in Berlin in October and is currently open to visitors on their online virtual exhibition.

Communicating non-communicable ideas

Much of what EDGE does is to use art as a medium to connect the public with science. There is a problem with public engagement with scientific research: only 32% of US adults say that medical researchers provide fair and accurate information. Much of this is because of the stereotype that scientists reside in ivory towers, publishing most of their data behind paywalls. But it’s also because their data is hard to understand for most non-experts. In fact, science is getting so complicated that it’s even becoming impenetrable for other scientists.

This is where art can help. Art is about trying to communicate ideas that are hard to grasp, and artists become experts in transferring ideas. Art is also accessible – everyone can experience, feel, discuss art in ways that are hard to do in science. Combine this artistic expertise with scientific concepts, and you have a way for experts and non-experts alike to interact with science on a different level. The powerful thing here is that the viewer isn’t just passively absorbing scientific information, but they’re actively participating in it. “I think making science approachable is hugely important,” Stewart says. “It’s not just about injecting knowledge, it’s about motivating people to enjoy and participate in science.”

Linda Alterwitz, Envisioning the Veil. Photography and mixed media (encephalography data printed on medical gauze, sewed with medical suture). In this piece, Alterwitz explores the relationship with our body and brains (seen in the recordings of human brain activity, metaphors for thoughts and emotions), and the sanctuary offered in the natural environment. Image credit: Linda Alterwitz.

Take SomaLab’s piece as an example. This multimedia installation uses data to represent how the brain processes visual information in real time. Viewers wear an electroencephalography (EEG) device which records the electrical activity of thousands of neurons in the occipital-parietal lobes of their brain (areas that process visual stimuli, among other things). This data is then analyzed and converted into a visual light display that is projected onto a wall, enabling you to see a representation of how the brain was processing the very thing it was looking at. If a picture paints a thousand words, this piece shows a dozen pictures.

Viewing science through an artistic lens

I keep coming back to Ardeleanu’s choice of words in saying that art is a useful tool to research the brain. To steer away from the scientific method of research seems like an unusual idea post-enlightenment, but can art provide complementary methods to the scientific process? Looking at the history of neuroscience, it would seem so. After all, it was partly for their beautiful drawings of neurons that Ramón y Cajal and Camillo Golgi won their Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine in 1906. In more recent years too, Nobel Prize winners Eric Kandel and John O’Keefe have explored interactions between art and neuroscience in various books and talks. Perhaps there is something to be learned from these big thinkers.

EDGE co-founder Tatiana Lupashina was keen to point out how getting scientists and artists to collaborate on artistic works, or even just to discuss scientific concepts, can be a huge benefit to scientists. “Many scientists have an image that their scientific work is sterile and objective, but so much of it is creative and subjective. Owning that creativity as a scientist is really powerful because then you think about your science in a different way. Art is a very explorative way to ask and challenge scientific questions, and there are so many mediums and techniques you can use for this.” She said.

Big discoveries are invariably made by scientists who have the vision to step outside of what’s already being asked. The more ways that scientists can think and feel about their work, the more it can help them to challenge their own understanding and create new associations. Art is a great way to do this – part of its duty is to constructively disrupt how we think about the world. The key is to bring scientists and artists together and provide spaces for this disruption. This is precisely what EDGE have done by bringing neuroscience and art together, just like Ardeleanu did with vision and sound, to create something that is greater than the sum of its parts.

Shahryar Khorasani. Dream II. Graphite, ink and watercolor on paper. Khorasani uses scientific and artistic symbolism to create windows into his dreams and subconscious. Image credit: Shahryar Khorasani.

Shahryar Khorasani. Dream II. Graphite, ink and watercolor on paper. Khorasani uses scientific and artistic symbolism to create windows into his dreams and subconscious. Image credit: Shahryar Khorasani.

Virgilio Vogels, Desert Room. Digital painting, print. Vogels depicts the situation of a patient diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia in a psychiatric clinic. Image credit: Virgilio Vogels

Source: Paint, Sculpture and Datasets: The Stimulating World of Neuro–Art | Technology Networks