Researchers have long known that the chemical structure of the molecules we inhale influences what we smell. But in most cases, no one can figure out exactly how. Scientists have deciphered a few specific rules that govern how the nose and brain perceive an airborne molecule based on its characteristics. It has become clear that we quickly recognize some sulfur-containing compounds as the scent of garlic, for example, and certain ammonia-derived amines as a fishy odor. But these are exceptions.

It turns out that structurally unrelated molecules can have similar scents. For example, hydrogen cyanide and larger, ring-shaped benzaldehyde both smell like almonds. Meanwhile tiny structural changes—even shifting the location of one double bond—can dramatically alter a scent.

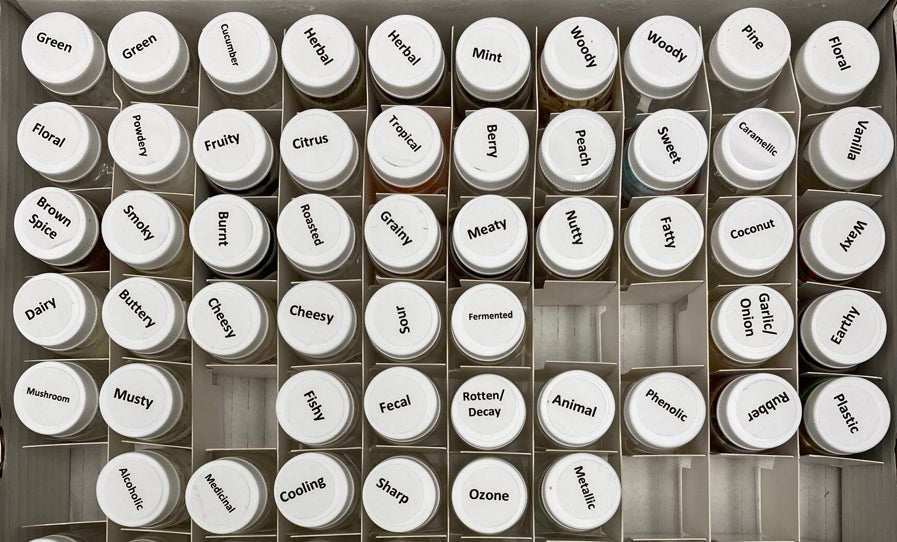

To make sense of this baffling chemistry, researchers have turned to the computational might of artificial intelligence. Now one team has trained a type of AI known as a graph neural network to predict what a compound will smell like to a person—rose, medicinal, earthy, and so on—based on the chemical features of odor molecules. The computer model assessed new scents as reliably as humans, the researchers report in a new draft paper posted to the preprint repository bioRxiv.

“It’s actually learned something fundamental about how the world smells and how smell works, which was astounding to me,” says Alex Wiltschko, now at Google’s venture capital firm GV, who headed the digital olfaction team while he was at Google Research.

The average human nose contains about 350 types of olfactory receptors, which can bind to a potentially enormous number of airborne molecules. These receptors then initiate neuronal signals that the brain later interprets a whiff of coffee, gasoline or perfume. Although scientists know how this process works in a broad sense, many of the details—such as the precise shape of odor receptors or how the system encodes these complex signals—still elude them.

Stuart Firestein, an olfactory neuroscientist at Columbia University, calls the model a “tour de force work of computational biology.” But as is typical for a lot of machine-learning-based studies, “it never gives you, in my opinion, much of a deeper sense of how things are working,” says Firestein, who was not involved in the paper. His critique stems from an inherent feature in the technology: such neural networks are generally not interpretable, meaning human researchers cannot get access to the reasoning a model uses to solve a problem.

Full article can be read by clicking link below:

Source: AI Predicts What Chemicals Will Smell like to a Human