Data scientists, artists and urban planners are mapping digital “smellscapes”, opening up new possibilities for virtual reality, real estate and how we understand the past. In the process, they are provoking interest from the UK’s biggest conservation charity. All three groups are exploring the ways in which smell influences environmental perceptions, using social media data and “smellwalks” to trace olfactory tendrils stretching through city streets.

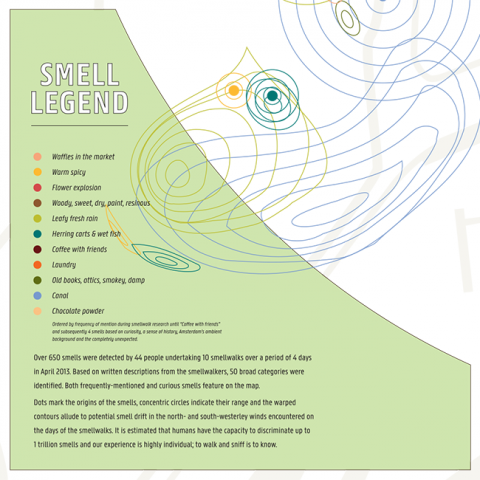

Luca Maria Aiello is part of a group of researchers with GoodCityLife.org, which maps urban smellscapes by tracking keywords online. It creates skeletal road maps with colour-coded strips: red for emissions, green for nature, blue for food, yellow for animals, and grey for waste. The Bayshore Freeway in San Francisco, for example, predominantly smells of emissions, according to the data. The project also ranks “Likeability”. The emotion most commonly affiliated with the freeway is “sadness”.

Aiello and colleagues compiled the percentages with the aid of the work of the late British urban planner Victoria Henshaw, and began their research by collating a dictionary of smell-related words she listed. “It was our first feat to look for words in social media, and then we [produced] … some sort of class word to put all these words together in microcategories,” Aiello explains.

Henshaw undertook smellwalks as part of her doctoral research, publishing a book called Urban Smellscapes in 2013. She used qualitative methods “including semi-structured interviews, participant drawings and direct observations” rather than social media data. GoodCityLife uses geotagging, and sifts through Twitter and Instagram to collect terms.

At this point, says Aiello, they could “map all the major cities in the world”. So far, they have traced the smells of 12 different cities “without spending too much money because this data can come for free from the public in the area”.

He acknowledged the potential for ‘noise’ in the data; corroborative evidence is vital in being able to compile accurate maps. Data availability levels are shown alongside street maps, and in some areas it is still low: further documentation is vital.

British artist and designer Kate McLean steps away from the “big data approach”, preferring the more “human” practice of walking out into the city. Aiello and his team used McLean’s methodology “as a way of confirming the data they gathered through hashtags,” McLean says.

On 28 February and 1 March, McLean will conduct two smell walks in London in conjunction with the Museum of Walking and The Flower Hut. She delightedly recollected previous events. “We had a group of 10 or so people going up to this biker and asking to smell him – it’s not illegal to smell people – just impolite,” she says.

She recalled a nonsmoker on a London smellwalk, who asked a stranger to breath a cloud of tobacco smoke on him. He just “really wanted to understand it,”she says. Recalling a trio to Pamplona, she says: “You get people arguing about what is being cooked five storeys up.” The olfactory cues acted as precursors to “imagined worlds”, where some visualised “a meat stew with tomatoes” being cooked and others bolognese.

Combining such work with the internet opens up several new possibilities. Aiello points to the implications for virtual reality. “You can think about an application that lets you explore places remotely… not only the visuals but the full sphere of perceptions of a space.”

He also details how it could affect the real estate market. House values should hopefully “reflect the positivity of the environment,” he says, adding that he hopes “to work with city officials to put up targets for interventions” as senses correlate with “something very tangible, which is the health of the citizens.”