At a show at the National Trust’s Rainham Hall in Essex. ceramics scented with figs and bay leaves evoke Elizabeth David recipes © Kofi Paintsil courtesy of AVM Curiosities.

A nose for history: how scent can bring the past into our homes

Perfumers and historians are using smells to recreate vanished worlds — and create new ones

Visitors to the current London: Port City show at the Museum of London, Docklands, are advised to lower their masks and inhale. A smellscape, designed to evoke the East End’s commercial past, will waft from the exhibition’s “Scents of Place” section. Whiffs of engine oil, tobacco and spices capture centuries of pullulating, seaborne trade, finally buried in the 1980s, before developers turned the remaining Victorian warehouses into loft apartments and offices.

To recreate those lost smells, Tasha Marks, an artist and olfactory curator, listened to interviews with dockworkers and combed the riverbank for clues. She learnt about tanneries, rank with curing mink skins, and storerooms full of tea and coffee in hessian sacks.

The resulting aromas — reproduced by commercial fragrance houses — were road-tested on former Docklands residents. The whiff of a rainsoaked docker’s jacket drying by a fire reduced one to tears.

“We live in a perfumed world — from fine fragrance to washing-up liquid — but what’s changed is the focus on smell’s narrative potential,” says Marks, whose scented installations have been displayed at the Royal Academy and Kensington Palace.

“I think about how smell can be used to change the atmosphere of a room and tell stories. Aroma allows us to craft a visceral experience in the mind of the viewer that goes beyond museum walls,” she says. “It can instruct, entertain and impart a sense of belonging. That makes it a powerful tool in the cultural sector: it opens up a new way to experience it.”

Artist Tasha Marks with a scented sculpture on display at the Wellcome Collection in London © Angela Moore courtesy of Wellcome Collection

Marks also works as a food historian, which was what ignited her interest in smell. “Taste is closely connected to smell, as many of us learnt during Covid.” She drew on culinary history for a current show at the National Trust’s Rainham Hall in Essex. Ceramics, scented with figs and bay leaves, evoke the recipes of Elizabeth David, whose friend, the Vogue photographer Anthony Denney, rented Rainham in the 1960s. Denney was photographer and stylist for David’s cookbooks, which brought Mediterranean food to flavour-starved postwar British tables.

In Nose Dive: A Field Guide to the World’s Smells, Harold McGee, who describes himself as a “smell explorer”, explains the biology: “[It] arises from two patches of sensitive skin . . . in the front of our head, behind and a little below our eyes . . . 400 or so different kinds of odour receptors recognise molecules in the air we breathe.”

These receptors send messages to the brain, which edits the “data” to create smells stored in our olfactory memory bank. Smells are “the most direct . . . and specific encounters with the molecules that make up the world”, he writes.

Which makes fragrance a compelling tool for museums looking for ways to entice visitors. “We’re more than visual creatures. By bringing scent to cultural spaces, visitors can understand an object or place in a more direct way,” says Roger Michel, executive director of the Institute for Digital Archaeology, which was founded in 2012 to conserve overlooked aspects of ephemeral heritage such as voice, dance — and smell.

“Unlike sight or sound, which we use to navigate the world, smell is often regarded as frivolous: the stepchild of the senses. But for man’s ancient ancestors it was vital to survival, to avoid danger and find food,” he says. “It plays a key role in our cognitive processes, informing how we experience places. Scientists are still mapping out our smell receptors — which is exciting.”

His olfactory experiments include recreating the Great Stink of 1858, when a miasma of raw sewage and industrial effluent in the Thames, exacerbated by hot weather, engulfed the capital. “Let’s just say we got it right.”

Covid-19 heightened our olfactory awareness. “[The idea of] losing our sense of smell made us realise how much it affects our mood,” says Amanda Carr, author of the We Wear Perfume blog. She says that smell can influence our emotions and notes a shift in the way fragrance houses are marketing their wares. “The tone has changed from the aspirational — buy this and be glamorous — to how smell makes us feel. We’ve spent so much time online that we want our scents to be experiential and immersive.”

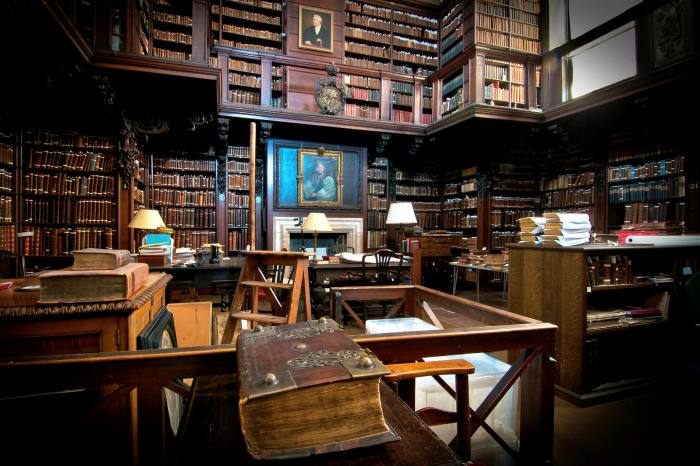

Sniffing the Magna Carta for a forthcoming exhibition at the Bodleian Library, Oxford

Locked into our own olfactory bubbles, we looked for ways to escape. Cue a surge in the sales of home fragrances.

“There was a move to joyful, exotic scents,” says Rebecca Rose, founder of To the Fairest perfumes. “With holidays cancelled, people wanted to bring an element of elsewhere to their interiors.” Online retailer Osmology saw a rise in sales of approximately 200 per cent in 2020 as home-trapped buyers found solace in its “Los Angeles” or “Wanderlust” candles “to evoke different atmospheres and memories”, says store owner Elizabeth Drew,

“Scent is deeply transportive. Through it we can inhabit cultures and continents that we’ve never been to,” says Justine Shaw of candle company Literati & Light, whose scents are inspired by literature (“Dorian Gray” smells of frankincense, ambergris and violet). “Because it’s present on the

borders of our experience, we tend to overlook smell. But when it takes centre stage in our consciousness it becomes as definitive and inspiring as any of its other showier sensory cousins.”

Smells can be captured in two ways. The perfumer’s method mixes synthetic molecules from different categories — floral, animal or vegetal — with preservatives to replicate aromas.

There was a move to joyful, exotic scents. With holidays cancelled, people wanted to bring an element of elsewhere to their interiors

Odours can also be extracted from objects by placing them in a sealed chamber. Purified air circulated inside passes through filters that trap airborne smell molecules. These are then extracted and combined with a water-based solution to produce a distillation of the original odours.

The latter is ideal for capturing the smells of precious objects. For Sensational Books, a forthcoming exhibition of rare manuscripts at the Bodleian Library in Oxford, Michel and his team analysed an “incense-infused” 15th-century Ethiopian gospel and the “mouse-nibbled” parchment pages of a 1217 copy of the Magna Carta. During the show, opening next May, these literary aromas will waft from vaporisers — heaven for bibliophiles who want to savour the “real and tangible” history of books, he says.

Entire libraries can also be captured in a bottle. For the Odeuropa Project, set up in 2020 to conserve our “smelly heritage”, independent perfumer Sarah McCartney of perfumery 4160 Tuesdays, co-author of The Perfect Companion: The Definitive Guide to Choosing Your Next Scent, investigated the aromas of St Paul’s Cathedral Library.

The resulting “leather, soot and vanilla-ish paper” notes demonstrated its antiquity. Her survey took place before the room was restored. Now, says McCartney, “we have a unique, sensory record of the space. It will never smell like that again.”

Sarah McCartney, a perfumer who ‘bottled’ the scent of St Paul’s Cathedral Library says it has ‘leather, soot and vanilla-ish paper’ notes © Chapter of St Paul’s/Graham Lacdao

Scented events have happened before, says Amsterdam-based art and olfactory historian Caro Verbeek, who uses smell to describe artworks to the visually impaired. “In the 1890s, fragrances were released over theatres to heighten dramatic moments,” she says. For the 1938 Surrealist exhibition in Paris, Marcel Duchamp installed a coffee-roasting machine to envelop visitors in “the smell of Brazil”.

The poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, founder of Italy’s Futurist movement, staged dinner parties that exploited all of the senses. Between nibbles of deep-fried roses, guests, clad in tactile layers of sponge or sandpaper, were spritzed with Italian cologne in a nod to the country’s rising tide of nationalism.

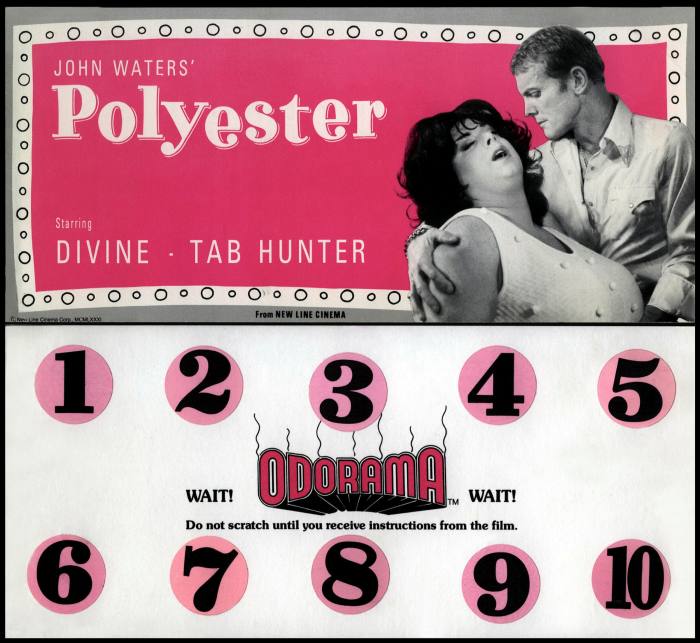

The 1970s and 1980s brought us scratch ’n’ sniff. Roger Michel remembers the scent-impregnated “Odorama” cards distributed to cinemagoers during a viewing of John Waters’ 1981 cult film Polyester, about the hidden horrors of suburbia. The malodours — dirty shoes, skunk spray — were “basic . . . but they added something”, he says.

‘Odorama’ card for John Waters’ 1981 film ’Polyester’ © TCD/Prod.DB/Alamy

The world’s most ambitious olfactory event took place at midnight on

January 1 2000. US artist Gayil Nalls had written to ambassadors across the world asking them to pick the smells that best encapsulated their country. The resulting aroma, “World Sensorium”, is “discordant and euphoric, like the sound of an orchestra tuning up for a performance”, says Verbeek. It was released over the crowds who packed Times Square to celebrate the dawn of the millennium.

In edgier, post-pandemic times, Marks hopes her scented interventions, at Rainham and the Museum of London in Docklands, will help to coax us back into the cultural sphere.

“I enjoy seeing people’s reactions to my work,” she says. “Smell unites, and divides. It provokes conversations and encourages people to be sociable. Everyone has an opinion because smell is part of who we are.”

Source: A nose for history: how scent can bring the past into our homes | Financial Times