Despite early enthusiasm for 3D, audiences have become increasingly hard to impress in recent years.CREDIT:MELISSA ADAMS

Remember how 3D was going to revolutionise the movie business? Benjamin Zeccola does, even if the memory of it just makes him laugh now.

“We’ve got 3D projectors in all of our cinemas, but we don’t really use them,” the Palace Cinemas boss says. “We dust them off and fire them up maybe once a year, just to make sure they still work.”

When the “new” technology of 3D – versions of which have in fact been around almost as long as cinema itself – exploded upon the scene in the late 2000s, it was hailed as the future of the industry. And for a little while, it was; audiences didn’t even seem to mind having to wear the clunky glasses, or pay extra for the privilege of doing so.

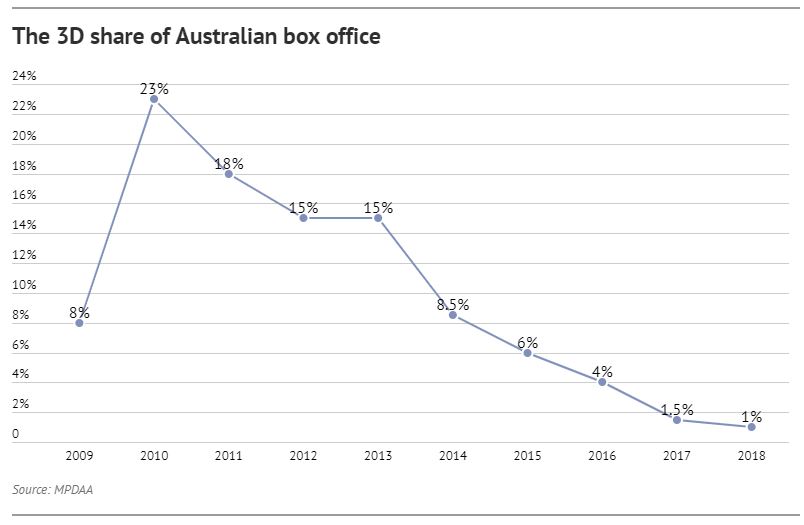

In 2009, 3D screenings accounted for 8 per cent of Australian box office. The following year – thanks to James Cameron’s Avatar and Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland – 3D took a massive 23 per cent share of box office locally.

The best example of that remains Cameron’s Avatar. Shot using twin cameras mounted about 6 centimetres apart, the film was so thoroughly embedded in the idea of 3D that initially Cameron planned not to even release a 2D version of it. In the end, its release was delayed until December 2009 to allow 3D projectors to be installed in as many cinemas as possible worldwide.

It worked, too: Avatar remains the top film of all time, having taken almost $US2.8 billion ($4 billion) worldwide.

It worked, too: Avatar remains the top film of all time, having taken almost $US2.8 billion ($4 billion) worldwide.

There have been other films that embraced the technology almost as fully as Avatar – Martin Scorsese’s Hugo and Burton’s Alice in Wonderland among them – but plenty of others have simply treated the medium as an afterthought, with films shot in 2D being put through the 3D conversion process after the fact, to absolutely nobody’s gain.

Though Cameron’s four Avatar sequels, due between 2021 and 2027, might yet provide a bump, 3D now appears to have been no more than a passing fad. Though there’s barely a blockbuster not released in a 3D version, and hardly a cinema in the country that can’t screen them, last year 3D accounted for less than 1 per cent of Australian box office.

Similarly, the 4DX experience – in which audience members are rocked in their hydraulically manoeuvred seats, while having air, moisture and scents squirted towards their faces – has not exactly caught on like wildfire.

Though Munari says it has been an enormously popular addition to Village’s offering since late 2017, drawing customers from far and wide, the hugely expensive-to-install concept is only available in two cinemas in Australia – Village’s Knox Century City in Melbourne and Event’s George Street multiplex in Sydney.

Palace’s new Platinum Class cinema at Como in Melbourne (following roll-outs in Perth and Sydney) includes concierge service upon arrival and food and wine delivered to the comfort of a leather recliner with a swing-arm table. Crucially, the food comes from nearby partner restaurants rather than a freezer- and microwave-equipped mini-kitchen on site. The wine list is similarly restaurant style (though thankfully not quite restaurant price).

“For all that,” says Zeccola, “the most important part of the experience is still the quality of what you put up there on the big screen.”

In a sense, there’s nothing new in any of this. The cinema experience has been constantly evolving since the invention of the medium 120 years ago. And, for better or worse, attendance has always been driven by change to the environment and the technology of the cinema.

The last time we went to the movies more than five times a year was 1974. Last year, the average Australian went just 3.6 times.

There was a brief bump from 3D, with attendances lifting from 84.6 million in 2008 to 92 million (an increase of almost 9 per cent) two years later.

But the harsh reality for anyone involved in the cinema business is that attendances are in decline, both on a per capita basis and in absolute terms. On the other hand, each of those customers is now worth a whole lot more.

Meanwhile, the box office has averaged $1.162 billion per year, up from $873.2 million a decade earlier. That’s a massive 33 per cent increase. And that’s just based on ticket sales.

In other words, cinemas are making their money by charging more per ticket, and for the most part they justify that by offering a more rarefied experience – be it through 3D, 4DX, plush armchairs and table service, or proper food and wine served in deluxe surrounds.

For better or worse, it’s a very long way from Jaffas down the aisles.